Advertisement

Commentary

'Just Ethel': What my grandmother, who was much more than a domestic worker, taught me about Black patriotism

Editor’s note: This article was originally published on Oct. 30, 2019.

In Aug. 2019, The New York Times Magazine launched the “The 1619 Project.” It was named to mark the arrival, 400 years ago, of the first enslaved Africans in the American colonies. The series, which includes more than 80 pages of historical essays, 17 original literary works, original artwork and a podcast, examines the many ways “the legacy of slavery continues to shape and define life in the United States.” The project was conceived of and led by magazine reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones.

After discussing it with the author of the essay below, the editors elected not to identify by name the family her grandmother, Ethel, worked for. In keeping with that editorial decision, we’ve blurred an image of Ethel posing with one of the family members.

***

For Black Americans, the past is ever-present. The past shapes what we believe and, for better or worse, it allows us to imagine what is possible.

I have been riveted by the entire 1619 project. But I was particularly struck by what Nikole Hannah-Jones has said (and written) about having complex feelings about patriotism. This passage is from her essay in The New York Times Magazine:

My dad always flew an American flag in our front yard. The blue paint on our two-story house was perennially chipping; the fence, or the rail by the stairs, or the front door, existed in a perpetual state of disrepair, but that flag always flew pristine ... that flag outside our home never made sense to me. How could this Black man, having seen firsthand the way his country abused Black Americans, how it refused to treat us as full citizens, proudly fly its banner? I didn’t understand his patriotism. It deeply embarrassed me.

For many Black Americans, it's like an abusive relationship. We love our country, but it does not always love us back. The best way I can grapple with this complicated dynamic is by looking back at my own family.

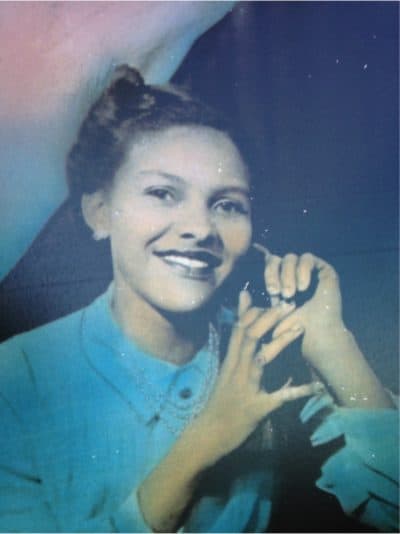

I have a picture of my grandmother, Ethel Phillips, posing with the great-granddaughter of her employer. The child is looking up at my grandmother as she smiles into the camera. They are both holding small American flags. My grandmother is wearing a light blue dress, which was actually a uniform.

For nearly 59 years, my grandmother was a domestic worker. She spent 43 of those years (1955 to 1998) working for several generations of one family in Dearborn, Michigan. Her inability to escape the servitude of that family has gripped me for years, partially because her story is also incredibly common.

Born in 1919, Ethel was the fifth of 16 children born in West Feliciana, Louisiana and raised in Darlove, Mississippi. She was quiet, shy and smart. Ethel was valedictorian of her 8th-grade class, but she never attended high school. When I asked her why, she always responded, “the school was too far away.” What Ethel did not know was that during the time there were only a handful of public high schools in the South that African American children could attend for a classical education.

Racial discrimination, segregation and violence kept even the most enterprising Black people from improving their lives in significant ways. Relocation from rural areas to urban settings or from the South to the North was all but required for those seeking better opportunities.

Ethel worked on her family farm until the age of 21, and then joined her older brothers and sisters in Inkster, Michigan. In the mid-20th century, because of the booming auto manufacturing industry, Detroit held the promise of better employment, a better wage and a better life. However, for many Black women, once they got there, domestic labor was the only job they could find.

As of 1960, one-third of all African American women who worked were employed as household workers. It was hard work and required significant time away from one’s own family. There were no unemployment benefits, worker’s compensation, pensions or social security.

During the Great Depression, southern Democrats blocked legislation that would enable Black Americans to receive federal benefits and protections. Sharecroppers and domestic workers — the majority of them African American — were exempt. Scholars have estimated that close to 70% of Black laborers were not working in sectors that would have included them under FDR’s National Recovery Administration. Accordingly, my grandmother worked for years into old age because she could not afford to retire.

Advertisement

But, ask anyone in her employer’s family and they will tell you that they adored Ethel. One told me, “She didn’t work for us, she was a member of the family.”

This word, “family,” has always troubled me. Everything about Ethel’s labor reflected racial and economic subordination. Practically everywhere she went, Ethel was known as “Mrs. Phillips.” But to her employers and their children, she was just, “Ethel.” The etiquette of formal address was never extended to domestic servants. Even after her death, members of the family asked me, “What was her last name?”

When Ethel arrived for work, she entered through the garage door. The front door was reserved for guests or real “family.” Throughout all her years of cleaning, Ethel never used a mop. She contended the only way to clean a floor was on your hands and knees. As a fair-skinned African American woman, washing the floors in this manner caused her knees to temporarily turn Black with calluses. While the floors were spotless, the stains of servitude were unmistakable on Ethel’s knees.

After her funeral, another family member wrote me a letter. He told me he kept a picture of my grandmother inside his laundry cabinet. He wrote, “It would be a late night…[and] I would be doing laundry and [I] would be so tired.” Then he would see the picture of Ethel taped to the inside of his cabinet and “know that every time I reached for the Tide detergent that I knew that I could do it all, too!”

The imagery of his recollection also suggests that he could not separate Ethel’s work or personhood from a commodity. For him, my grandmother was a proverbial “Mrs. Clean,” who came to life and befriended him during childhood. In the same way that many Americans conjure up warm or nostalgic feelings for products advertised with Black bodies such as Aunt Jemima’s Syrup or Uncle Ben’s Rice. Black humanity is rendered as flat as the packaging.

When my grandmother finally stopped working, she was 79. Her story is not unique. In fact, it is representative of many marginalized Americans and undocumented workers today. It explains why cultivating generational wealth was — and is — so crucially important. While all of my grandmother’s descendants are educated, education is not wealth. In some ways, higher education is debt. This kind of structural inequality prevents retirement, promotes subordination and offers no protection. I wish my grandmother was the exception, but she remains the rule. Her life taught me that “good bosses” aren’t just kind. Good bosses provide safeguards, opportunity and dignity.

The 1619 project reminds me that African American progress both individually and collectively can feel unobtainable in the face of discriminatory legislation, racist policies and exploitative practices. And so, for some of us, waving a flag can feel dishonest.

That said, I am also reminded that it is Black Americans who continually fight to overturn these injustices. When I think of what has been accomplished from my grandmother, to my mother, to me, waving the flag can also feel like hope.