Advertisement

Commentary

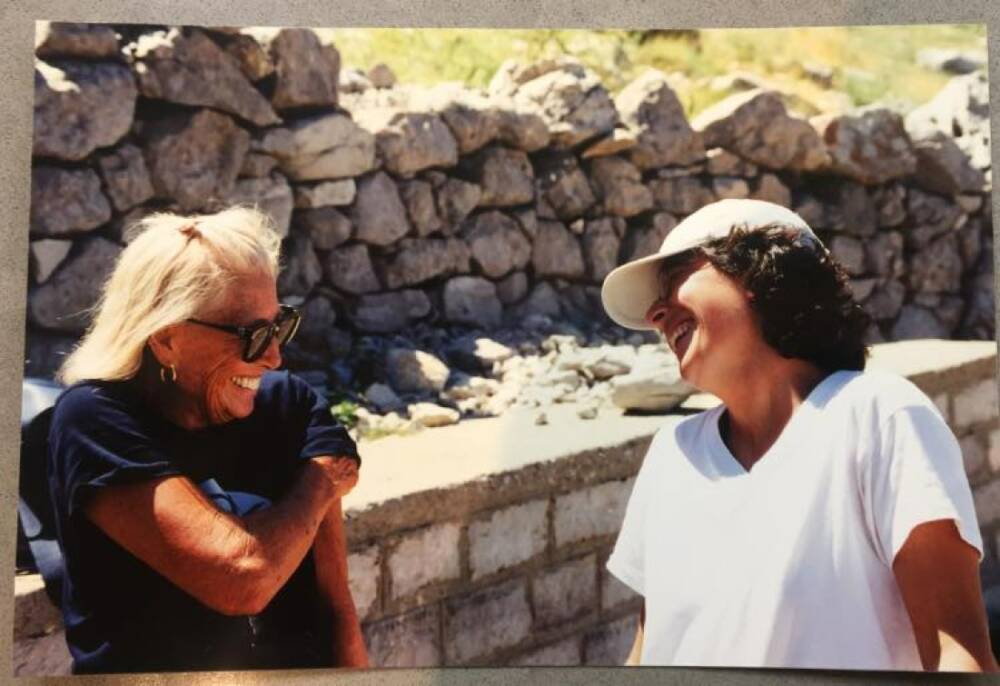

The love letter my mother never sent me

One spring a few years after my father’s death, I helped my mother empty her house in the Boston suburbs in preparation for her return to her native Greece. After 54 years in the United States and 45 years in a contemporary house at the top of a wooded hill, she was going back to live year-round in a light-filled Athens apartment with a view of the Parthenon.

The move, in 2015, made sense for my mother. In Athens, she would be near her relatives, and even talking to them on the phone would be free from the seven-hour time difference. But the biggest reason behind my mother’s return went unsaid. Moving thousands of miles away from me would be a relief for us both.

We started the packing process in her bedroom. I prepped the stacks of design and fashion magazines for recycling while she went through photos and papers in her nightstand. At one point I became aware that she had gone still. She had found a letter she had written to me back in March of 1981 after visiting me at Oxford on my junior year abroad.

She began reading aloud, and then she got to this: “I shut our moments and froze them so that I can forever see you walking beside me, not the little girl you were, holding my hand, feeling sheltered, but the friend, the grown-up, the interested, the knowledgeable, the secure (the one who rolls her eyes in the sky, now and then).”

I shut our moments and froze them so that I can forever see you walking beside me ...

Letter from the author's mother

I didn’t know what to do except to fight back tears. All my life, my mother occupied the center of a world whose energies were all directed inward, towards her. When I was with her, I felt excitement but also fear and sometimes, shame. There was always a sense that our hard-won equilibrium would alter and everything would tip into catastrophe, as it often did. But in this letter, my mother was being generous, thoughtful, nurturing. She was offering and confessing love, instead of telling me, as she often used to do, that she didn’t love me anymore.

In the letter, she expresses what I know now to be the best version of herself. She is eloquent and funny. She's lighthearted. She blends her wit with deep emotion that, even now, is difficult for me to read. "We walked together and we talked together, we had tea or was it coffee," she wrote, recalling a joke we had during her visit. "And by the fireplaces, where I was cherishing my biscuits, invisible threads bounded us close together. For I was loving you very much, I was proud of you, and happy, in spite of all my blisters on my toes."

When she finished reading the letter, we both wiped our eyes. She must have felt a bit exposed, to have allowed me to see how strong her emotions had once been — and perhaps were still. And I felt embarrassed: for not having been closer to her over the years, for not being able, right then, to hug her, for not being able to listen to this letter without sorrow. I knew there had been good reasons for me to keep my distance — my desire to shield my own children from expressions of her love that were shockingly conditional, my recognition that she wasn’t terribly interested in being part of our lives. But at that moment, I felt undeserving of the old letter’s fleeting kindness. I felt undeserving of this mothering.

For I was loving you very much, I was proud of you, and happy, in spite of all my blisters on my toes.

Letter from the author's mother

I had always wanted a mother. Mine must have been unprepared, even at 36, to take me on. Her own mother doesn’t seem to have been an especially involved parent, though when she died in the final months of my mother’s pregnancy with me, her absence was profound. Never informed of her mother’s illness, then unable to travel to Greece for the funeral because of her advanced pregnancy, my mother entered motherhood six weeks early, her labor said to have been brought on by grief. She mourned her mother at the same time that she became one. Perhaps those early months with a premature infant made her feel I was a poor substitute for what she had lost.

Only after my own first child was born could I understand how the trauma of my grandmother's death must have shaped my mother’s life. But by then, it seemed too late. As I had begun an independent life, a marriage, a family, I’d held my emotions and experiences away from her, fearful that if I shared them, she wouldn’t care. We went months with my father serving as the only link between us. When he suffered a massive stroke, I saw my mother for the first time in weeks. Fresh from cataract surgery the previous day, she stood at the end of an Emerson Hospital corridor, tiny in a white t-shirt and jeans, an eye-patch giving her a horrible rakish air. As if I were first laying eyes on my newborn child, I knew instantly then that she was mine to take care of.

I reminded myself that she was just an old lady, and one with qualities that I admired. She painted and sculpted, she drove a stick-shift, she wore three-inch heels, and she could still do a full split even into her 90s. Before she sold her suburban house, she used to haul the ladder out from the garage and wash her own plate-glass windows, two stories up. She read histories of Byzantium for fun. But my best efforts to connect — and hers — eventually succumbed to emotional fatigue, and she remained a mystery to me.

My mother never sent that letter she’d written to me in March of 1981. She wrote it and stuck it in her nightstand drawer. The thought that she might have been too afraid to share those emotions with me makes me deeply sad. What would our relationship have been like if I had read the letter back then, on the cusp of adulthood? Would I have understood that I was loved? Would I have understood how difficult it had been for her — even if I didn’t know why — to let me in, and would I have been able to ease her worries?

Sometimes I think I never met the woman who wrote that letter. Still I keep it in a box where I store the documents from my life’s most important relationships. It’s there with the love letters. And why not? Because that, for better or for worse, is what it is.

Let this essay — because it's all I can do — be my reply.