Advertisement

Commentary

100 years ago my grandfather emigrated from China. He never could have imagined a Mayor Wu

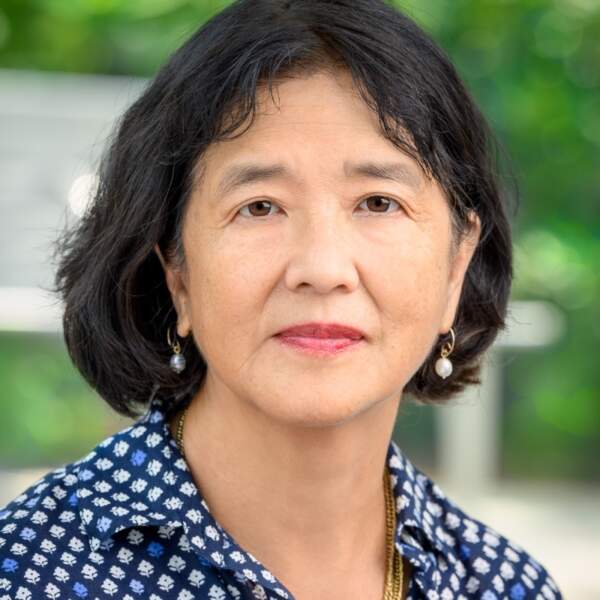

When Michelle Wu was elected as the first Asian American woman to serve on the Boston City Council in 2013, my family was thrilled. When she was elected mayor of Boston in 2021, we were ecstatic. To us, she represented the promise of rising Asian American political power. A promise that began — for our family anyway — with my grandfather. He was one of Boston’s early Asian American sojourners whose political acumen would have earned him an elected office if America had been ready for him — if he had been born a few decades later.

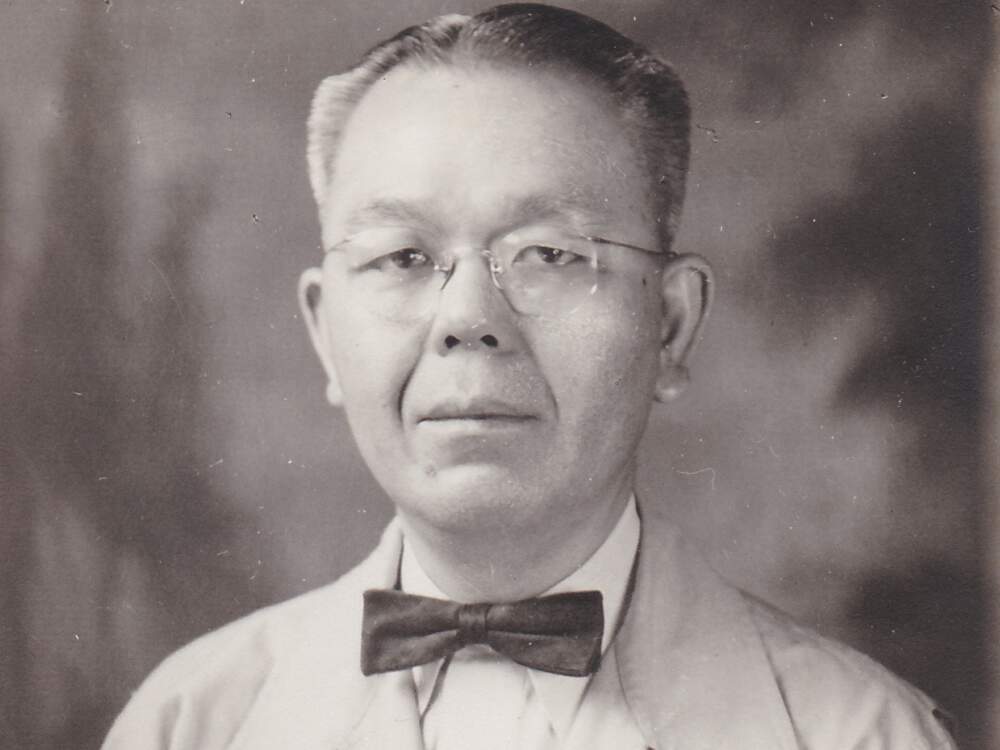

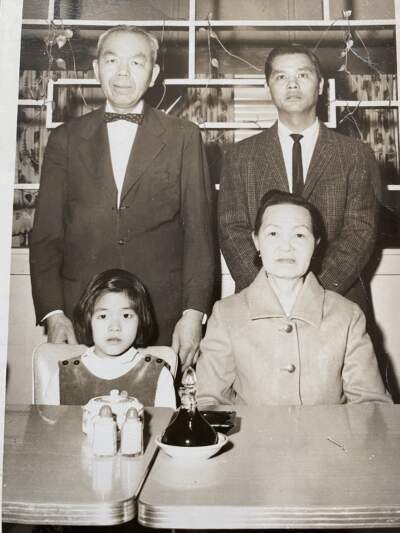

My grandfather came to the United States alone in 1923. His name was YeeSoon and he went by George, but Chinese people never refer to their elders by their first name, so even as an adult, I only think of him as grandfather. While the details may differ, his story is representative of Asian American experience in the early 20th century.

When he emigrated from China, America was hostile to the Chinese. Late in the previous century, growing nativism and competition with domestic workers had led to the enactment of a series of laws colloquially known as the Chinese Exclusion Act. When that act expired in 1892, Congress continued to limit Chinese immigration with the Geary Act.

These acts of exclusion, which were repealed in 1943, remain the only immigration laws in American history to single out a particular ethnic or national group. The few exceptions were for merchants and businessmen, but even they were not allowed to stay in the United States permanently or become U.S. citizens. Chinese migrants like my grandfather could only be “sojourners.”

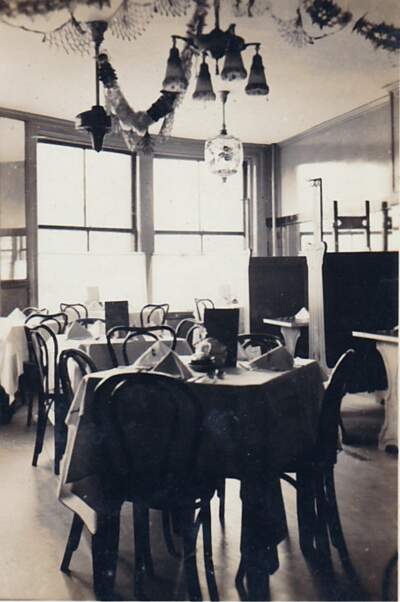

Fleeing anti-Chinese sentiments in California, my grandfather made his way to Massachusetts to open The Republic Restaurant (共和樓) in the city of Malden, about 10 miles outside Boston. He named the restaurant The Republic to honor the newly established Republic of China, which had emerged after 2,000 years of dynastic rule. Coming of age during a revolution gave my grandfather a strong sense of nationalism. Naming his first restaurant after the republic instead of choosing a more common name like Golden Lotus or Jade Fortune signaled his concern about issues beyond commercial success.

Still, The Republic proved to be a successful business. In fact, it was so successful that other Malden residents told my grandfather he should run for a seat on Malden City Council. Given his political savvy and business acumen, he would have been an ideal candidate and he was tempted. But, ultimately, he decided not to run. “America was not ready for a Chinese-American councilman,” he told me. “It would be more gracious to decline than to suffer a defeat.”

Advertisement

In my grandfather’s day, blatant racist stereotypes painted Chinese-Americans as alien, inferior and weak, stereotypes that led not only to legislation like the Chinese Exclusion Act, but also to anti-Asian violence, including the Los Angeles Chinese massacre of 1871. Instead of running for office, my grandfather settled for marching with other notable businessmen in Malden’s annual Fourth of July parade. I can see him in my mind’s eye with his suit and ever-present bowtie, marching in the most American of all holiday parades.

And while he didn’t have a place in mainstream American politics, my grandfather devoted himself to the “huiguans” — guilds or associations — in Boston’s Chinatown. The huiguans were the social and political backbone of our immigrant community, which was often isolated from and ignored by the rest of American society. Much to my shame, I dismissed these organizations as old-fashioned and irrelevant. Once, when my grandfather made a large donation to one, I chided him for being gullible.

“But I am an elder of the association,” my grandfather replied. “I must set an example.”

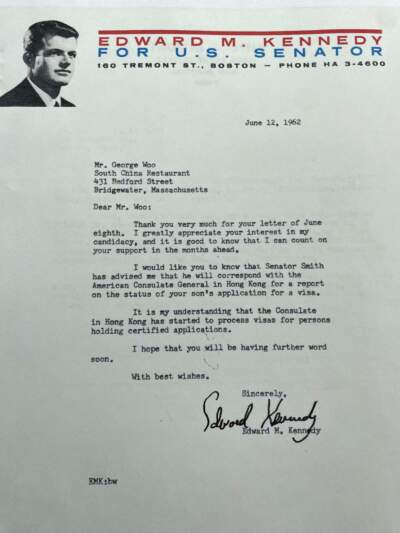

When the exclusion laws were repealed in 1943, my grandfather became a U.S. citizen and spent the next 17 years contributing to, supporting and lobbying elected officials on behalf of our family, which had sought refuge from the Chinese Civil War in Hong Kong. A politically savvy man, my grandfather crossed party lines and worked diligently as a volunteer for Ted Kennedy’s Senate campaign and John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign, hoping it would help our cause.

My grandfather would later recount — always with the hint of a smile — how he was often the sole Asian American in the room at campaign rallies. He was such an anomaly that each of the Kennedys, including JFK himself, would cross the room to shake my grandfather’s hand. At almost six feet tall and slightly stooped, my grandfather stood out. He was a distinguished figure.

These acts of exclusion, which were repealed in 1943, remain the only immigration laws in American history to single out a particular ethnic or national group.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 eventually helped many families like ours immigrate to the U.S. But a year before that act became law, my grandfather received a congratulatory telegram from Sen. Kennedy, informing him that our family’s application for immigration to the U.S. had been approved. The approval for our entire family of eight, an unusually large number, shook Boston’s Chinatown. My grandfather wasted no time: It took him less than two months to complete the documentation for my family’s travels. And in late July 1964, we boarded the S.S. Cleveland and commenced our journey to Boston.

It would be nearly 50 years before we saw a Chinese American on Boston’s city council, and another 60 before we elected a Chinese American mayor. My grandfather was right: Boston wasn’t ready in his time.

And what about now? Asian American voter turnout spiked in the 2020 election. In fact, between the 2016 and 2020 U.S. presidential elections, Asian Americans increased their turnout rate by more than any other racial or ethnic group. But Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) are still dramatically underrepresented in elected office. As of May 2021, AAPI people made up 6.1% of the U.S. population, but only 0.9% of U.S. elected officials.

And while California’s 1913 Alien Land Law — which made the state so inhospitable to people like my grandfather — no longer exists, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis just signed three bills aimed at limiting “the malign influence” of the People’s Republic of China. SB 264 prohibits any Chinese individual without U.S. citizenship or lawful permanent resident status from owning property in Florida altogether. Chinese visa holders are allowed to own one home, but must complete a special registration with the state government to do so.

Even as we celebrate the accomplishments of Michelle Wu, anti-Asian sentiment smolders. A “model minority” myth complicates matters with seemingly positive stereotypes that oversimplify the history of Asian people in America and obscures the bamboo ceiling that has limited so many of us, including my grandfather.

My grandfather’s political efforts had to be small and invisible because America wasn’t ready for him. So instead of working for the city, the commonwealth or his country, he worked for his huiguan and his family. He was right: it was important that he set an example. He would have been proud and thrilled to witness the election of leaders like Michelle Wu — leaders who stand on his shoulders. I will honor him by making sure that others will follow.