Advertisement

Commentary

‘Papi’ is the person I remember — the one from my memories

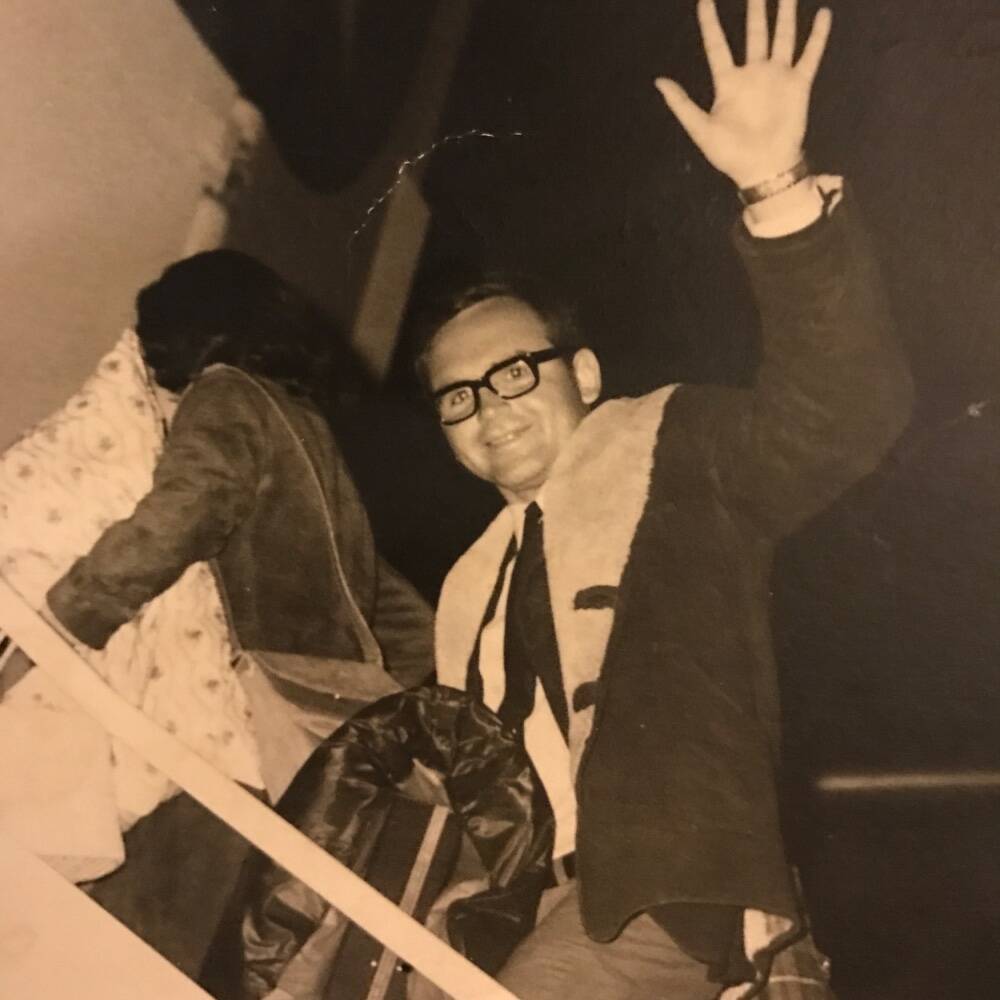

My grandpa, Hugo Palavicino, immigrated from Chile in the 1970s amid political and social unrest. He settled in New York City, determined to build a new life. He arrived with a small carry-on and $10. My grandpa’s relentless determination and prudent choices enabled him to persevere and ultimately provide for his family. He remained dedicated to their well-being, despite the challenges he faced.

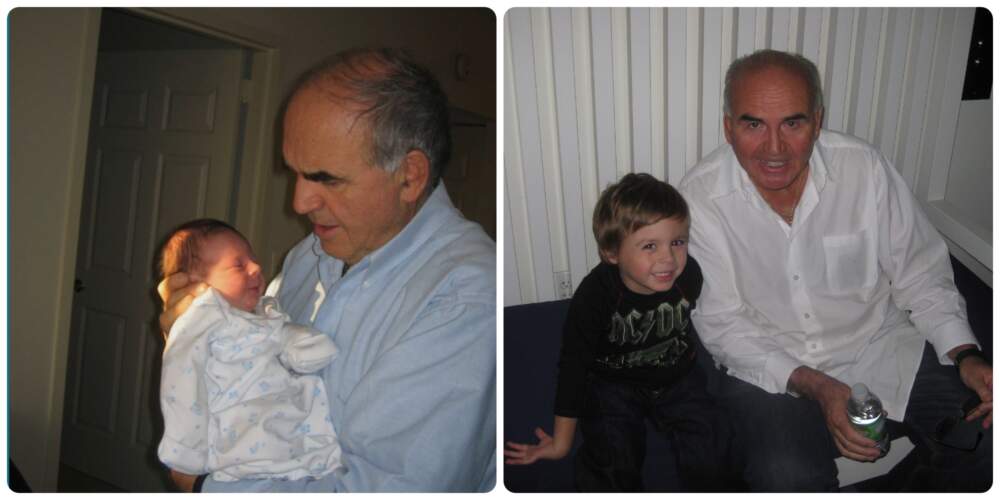

Growing up, my grandpa was always by my side. We built cities out of my Lightning McQueen car characters and role-played games in which I was a Marvel hero, and he played the villain — always ending in me tackling him. With my endless energy, my grandparents regularly took me to the park, where my grandpa would try to teach me how to play tennis. Whenever I became frustrated, when the ball kept flying over the fence, he would laugh and encourage me to try again.

About six years ago, at the age of 70, my grandpa was diagnosed with dementia, a general term for memory loss and other cognitive abilities. However, as time passed, it became clear that he had Alzheimer's disease, a more severe form of memory impairment. I was 9 years old at the time of his initial diagnosis, and my family had just moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts. I didn't think about it much at first. I was busy hanging out with my friends, reading comic books, building Legos, and making stop-animation videos. I didn't understand, yet, how it would affect my grandpa and my family.

Alzheimer's disease is one of the leading causes of death in adults aged 65 and older. Approximately 21.3% of Black Americans and 13% of Hispanic Americans live with Alzheimer's disease, and cases among people aged 65 and older from the Black and Hispanic/Latino population are expected to quadruple by the year 2060. Studies have shown that Latinos, like my family, are more likely to develop Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia at a younger age and are also more likely to be diagnosed later in the disease.

For my grandpa, the situation became serious when my grandma could no longer care for him alone. They had to move in with us to ensure that he received proper care and support. The transition, while sometimes stressful — having to help my grandpa take his medicine and calm him down when he was confused — also brought me joy. The opportunity to spend more time with my grandparents was a source of happiness for me.

But when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, human interaction became limited. In my opinion, this was the biggest factor in my grandpa’s rapid decline. At home, now, I help my grandpa amidst all of his confusion. I assist him with showering, getting dressed, brushing his teeth, cutting his beard, and other daily necessities. Each day, I witness firsthand the devastating effects of memory loss on a person.

I still struggle to comprehend how someone as important as my grandpa could be so harshly affected by this disease. My own thoughts often feel scattered — and complicated. So when my 10th grade humanities teacher asked us to create a poem, I knew I wanted to write about my grandpa,"Papi," and my experience as his grandson during this time when he both is and is not himself. I wanted to capture what life is like, the questions I often ask myself, and how my time with my grandpa has changed my life.

Advertisement

As I reflect on my grandpa, I find myself fixating on the notion of memory, which is crucial to our identities as individuals. I have a lifetime of memories with my grandpa, who was the patriarch of my family for so many years, the solid rock everyone looked up to. I wonder, does his essence as a person stem from my memories of him, or his own recollections? Are his memories ultimately what define him? There are moments when he is lucid, and my own memories of who he was in my earlier years come flooding back for a brief moment. Then I feel lost, and sad, knowing he is slowly fading away from us.

However, when I recall my childhood memories, they evoke the feelings of love and affection that I still hold onto. I tried to capture this in the poem because, to me, they are as real as the devastation of what’s happening now. These memories keep my grandpa alive in my heart; they remind me of the man he once was.

I choose to believe that my grandpa is the person I remember — the one from my memories. Even though it's difficult to find hope when I see the lost look in his eyes as he gazes into the mirror, I choose to view consciousness through the lens of my own memories. That way, Papi will always be the giant I looked up to when I was young.

“Papi”

What is a memory?

Is it simply what we remember?

Or is it what a person means to me?

Sometimes it feels like what was once clear is now burnt to embers.

When Papi looks in the mirror,

Does he know the man standing in front of him,

Or does he simply stare until something else catches his attention?

His mind is an endless blur,

Some days he’s gone, and some days, he is there.

Does Papi come from what he remembers, or what we remember of him?

When I was a boy, he was like a giant, someone that I had to look up to.

In the echo, he resides in the grainy young memories filled with love.

But the most current and clear memory of him is one of confusion.

The Papi of memory was always clear, not the Papi in front of me.

Although he might seem like a living, breathing creature,

His body remains tangible even as his consciousness fades away.

Is it without meaning?

What path does one’s self follow without memory?

What is a living being without an authentic consciousness?

Is it our memory that separates us from the animals?

Does a dog not remember its owner?

What even is the right criteria for a working consciousness?

What one sees, feels, or believes is all relative,

Except for Papi. I know he is not relative.

He is everything I remember and everything he sees in the mirror.

Author’s note:

I want to thank my Humanities teacher, Ms. Lauren Lamb, for encouraging me to find my own voice and experiences in writing, inspired by Langston Hughes' work during our study of the Harlem Renaissance. Thank you for your dedication to teaching and inspiring me to write a poem that is true to me.

This segment aired on June 29, 2023.