Advertisement

Commentary

How do you mourn a tree?

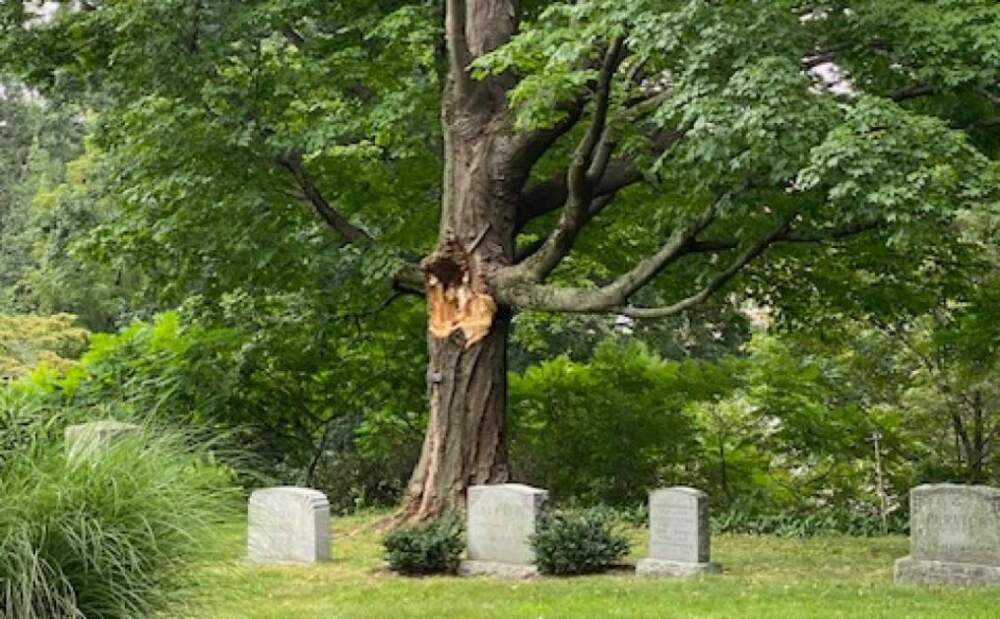

The morning after a recent microburst, a friend sent a disturbing photo from Mount Auburn Cemetery. “Look what happened to Tree #65, the wonderful maple at the start of the Blue Trail,” she wrote.

I gasped. Her picture showed a majestic sugar maple with a broken limb and a deep

cavity in its center. She had heard that the tree would probably be destroyed, so she suggested we might want to “stop by and pay our respects.”

If that sounds personal, it is. My friend and I and other volunteers, have kept track of this tree for seven years. We are part of Mount Auburn Cemetery’s phenology program, which monitors natural changes in relation to climate. Through the growing season, we keep track of when trees bud and leaf out; when flowers form, swell and open. We note when trees bear fruit; when leaves change color and drop in the fall. We have learned the idiosyncrasies of our trees: which oaks drop their acorns first, which dogwood produces few flowers when another is abundant. We know to avoid the female ginkgo in the fall when she drops her noxious-smelling fruit.

We have learned the idiosyncrasies of our trees: which oaks drop their acorns first, which dogwood produces few flowers when another is abundant.

Numbered tags identify the trees on three routes: Red, Green and Blue. Sugar maple #65, on the Blue Trail, sits like a sentinel at the top of a rise. It has a lovely, conical shape. Though it is the last of the 65 trees we monitor, those of us who walk the Blue Trail like to begin our observations there. In the spring, we aim our binoculars at #65’s high branches to see if it is flowering. We peruse the tall grass at its feet, looking for any seeds (called samaras) that the squirrels might have missed. In later observations, we note a weak branch on the trunk’s left side. In the fall, we photograph its brilliant golden canopy.

I thought back to 2022, when this tree — along with every other sugar maple on our

route — bore no fruit. Had they made a pact to rest that year? Did they sense something about the weather that caused them to hold back? This year, all our sugar maples — including #65—produced an abundant crop of samaras that swirled to the ground like tiny helicopter wings.

Most trees in the cemetery are identified by name and date planted. But #65’s tag only shows its Latin name: Acer saccharum. When I check with the cemetery office, they can’t find a planting date for the tree. Could it be older than the cemetery, which was founded in 1831?

In the first years of our study, we kept records for the cemetery’s own interest. Now our data is submitted to a national database. Our work is inspired by the research of Boston University biologist Richard Primack, who studies how a warming climate affects the plants and birds of Massachusetts. Primack has compared current data to records kept by Henry David Thoreau of Concord, in the 1850s.

Primack’s work — and our observations — have shown us that trees leaf out weeks earlier than in Thoreau’s time.

Primack’s work — and our observations — have shown us that trees leaf out weeks earlier than in Thoreau’s time. They hold onto their leaves longer in the fall. When trees produce leaves earlier, insects hatch out in sync with them. When migrating birds arrive at their usual time, they may find the insects they rely on to raise their young have already finished their cycle, threatening their fledglings’ survival. This is just one of many worrisome disruptions taking place in the natural world.

Climate change has been especially dramatic this summer, causing many of us to wonder if we’ve reached that “tipping point” that climate scientists have warned us about. Heat has broken records around the globe; Canadian fires sent smoke as far south as Washington, D.C.; temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean registered an astonishing 101 degrees Fahrenheit; torrential rains flooded many areas of Vermont; fires burned through the tropical forests of Maui.

When I first heard the news about our wounded tree, I went to pay my respects and was shocked to see the hole in its heart. Still, its great, heavy limbs were all intact. Perhaps the tree could be saved?

I went away for a week. On my return, my friend sent another photo: this time of an

enormous, flat stump. I hurried to the cemetery and climbed the hill, shocked to see the wide, empty space in the sky that the tree once filled. It’s only one tree — yet its demise is emblematic of all we may lose, if we don’t turn down the heat on our planet. I closed my eyes and mourned.