Advertisement

Commentary

The outrage at Harvard, Penn and MIT is rooted in American anti-intellectualism

So what if these women headed three of the greatest research universities in the world? Or that these institutions had their fingerprints all over the credentials of recent Nobel Prize winners? Many of the representatives on the congressional committee grilling the presidents of Harvard, MIT and Penn at a December 5 hearing were far more interested in easy soundbites than real evidence or complex narratives. They were out for blood, not subtleties: Answer: Yes or No!

For five hours, Elizabeth Magill, Sally Kornbluth and Claudine Gay — respectively the presidents of the University of Pennsylvania, M.I.T. and Harvard, and outstanding scholars in their fields — tried in vain to use a kind of academic logic and legal context to educate their attackers. They testified that they too were appalled by antisemitism and that they did believe in the right of the Jewish state to exist.

But when it came to disciplining students for speech, even for the horrendous use of specific words, including intifada and genocide, the intellectual lobes of their brains took over and the old mantra — “The only thing better than free speech is more free speech”— gripped them.

Facing hostile questioning, but aware of their faculties and others waiting at home who would scream just as loudly if their words seemed to threaten free speech, the three waffled. They tried and failed to dance on the head of a pin about invoking genocide as a form of free speech. (Magill resigned from her post at Penn on Saturday afternoon.)

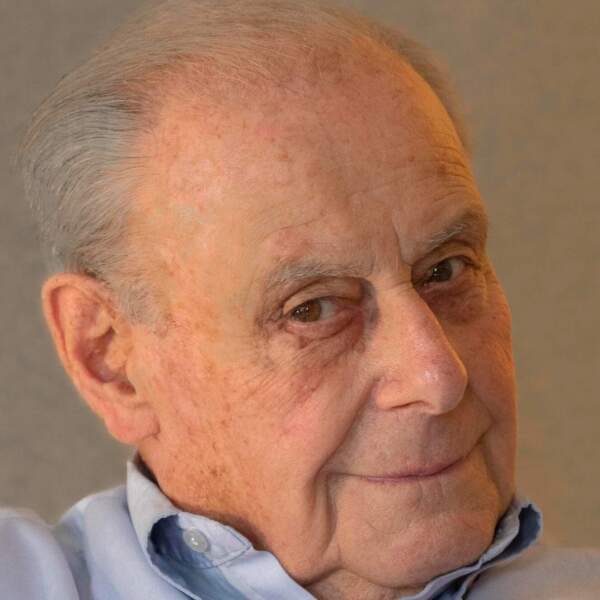

I was a professor of Judaic Studies, mostly literature and Yiddishkeit, for more than 40 years, occasionally also lecturing on Zionism.

Earlier in the five-hour hearing, Rep. Elise Stefanik (R-NY) had already asked the presidents about whether speech in support of intifada or calls for violence against Jews would lead to disciplinary action against students. Such “hateful, reckless, offensive” speech is “personally abhorrent,” Gay replied, but free speech demands that action be taken only “when speech crosses into conduct.” The presidents thus walked right into a narrative trap that had been already set, namely that anti-Zionism or even opposition to Israeli policy equals antisemitism. Groups such as AIPAC and the ADL have won the battle of controlling the narrative and gaining congressional approval. Criticism of Netanyahu or rampaging Israeli settlers? That’s antisemitism.

True — some of those condemning Israel today are also anti-Jewish. They really are virulent antisemites. But nuance was not on the congressional agenda last week. Bringing down three academic giants, three extraordinary women scholars, most certainly was.

Beating up on our own higher education system has been a favorite American sport since long before the Israel-Hamas war. Americans have long preferred their heroes to be relatively uneducated — think the Wright brothers, Thomas Edison and Charles Lindbergh, who dropped out of college after one year. Stefanik thus reflected — and went to town with — basic American anti-intellectualism; these three women were her perfect target.

No matter what they say or do now, the two remaining presidents will continue to be pilloried. But they ought to remain in their positions and defy this unjust witch hunt: caving now would be worse than falling on their free-speech swords.

I came to Tufts University in 1964. As I cringed through the December 5 hearing, I thought of some of my own experience as both a professor and administrator.

I was a professor of Judaic Studies, mostly literature and Yiddishkeit, for more than 40 years, occasionally also lecturing on Zionism. My approach was to just teach the facts. I’d explain that Theodor Herzl was a secular Jewish European, who, after the Dreyfus Affair Trial, wanted a secular Jewish state, with German as its language, and no religious test. He thought of Argentina as a possible Jewish homeland, later Uganda, and after Zionist Congresses from 1897 to 1904, he was negotiating for Kenya when he died at 44 years old in 1904, after which the Zionist movement focused on Palestine.

After this class, students would often come forward and ask, “So what is your opinion on Zionism?” My answer was always the same: “None of your business. Make up your own mind.” This is a subject best taught by keeping your own opinions to yourself.

I have lived through what is arguably the Golden Age of American higher education, but try convincing most of the public, let alone a polarized Congress.

Our research universities are the greatest in the world. Even the Chinese, in spite of spending hundreds of billions of dollars to catch us, have accepted American research hegemony. Their own Shanghai University Rankings of World Universities gave to American institutions 12 of the top 15 positions: Harvard was first, MIT third, the University of Pennsylvania, 15th.

Stefanik thus reflected -- and went to town with -- basic American anti-intellectualism; these three women were her perfect target.

Over the past 20 years, the United States has a $36 billion trade surplus in higher education. We dominate the Nobel Prizes. But no degree of success can prevent the majority of Americans from believing that our higher educational institutions are failing, that, as a recent Wall Street Journal contributor wrote:

The biggest threat to our future isn’t climate change, China, or the national debt. It is the tyrannical grip that a hopelessly corrupt higher education now has on our national life.

American higher education is more than research. Students — many of whom are young enough to still get medical care from their childhood pediatricians — go to thousands of colleges to grow up, learn new things, make new friendships and, often by accident, find a career path that may prove startling to themselves and their surprised parents. They take risks, fail at times, grow — and commence into a world of lifelong learning. That’s college in America, and there is nothing like it anywhere in the world.

There is no Swarthmore in China, no College of the Holy Cross in Russia, no Bryn Mawr in Iran, no Hillsdale in the European Union or Great Britain. American higher education is not a “system;” it is not part of a federal state of civil servants, such as is found in the European universities, where the faculty must gain permission to change universities. Students here are not told when they are just 11 or 12 years old: Here is your career path; this one cleans toilets; that one becomes a doctor.

Without a doubt, some of higher education’s wounds are self-inflicted. Billions of dollars are wagered on intercollegiate sports, athletes are bought, hired, paid, often learning little or nothing. There are admissions scandals, faculty immorality, research fraud, other ailments and problems. And there are truly awful periods, like the ones embroiling campuses today. Yet for all of that, for all of the steady din of negative comments and columns, American higher education remains the envy of the world.

Except at home.

Sol Gittleman is professor emeritus and former provost of Tufts University. He is the author of “An Accidental Triumph: The Improbable History of American Higher Education.”