Advertisement

Commentary

Here's a bold solution to women's health care: Train doctors to listen to women

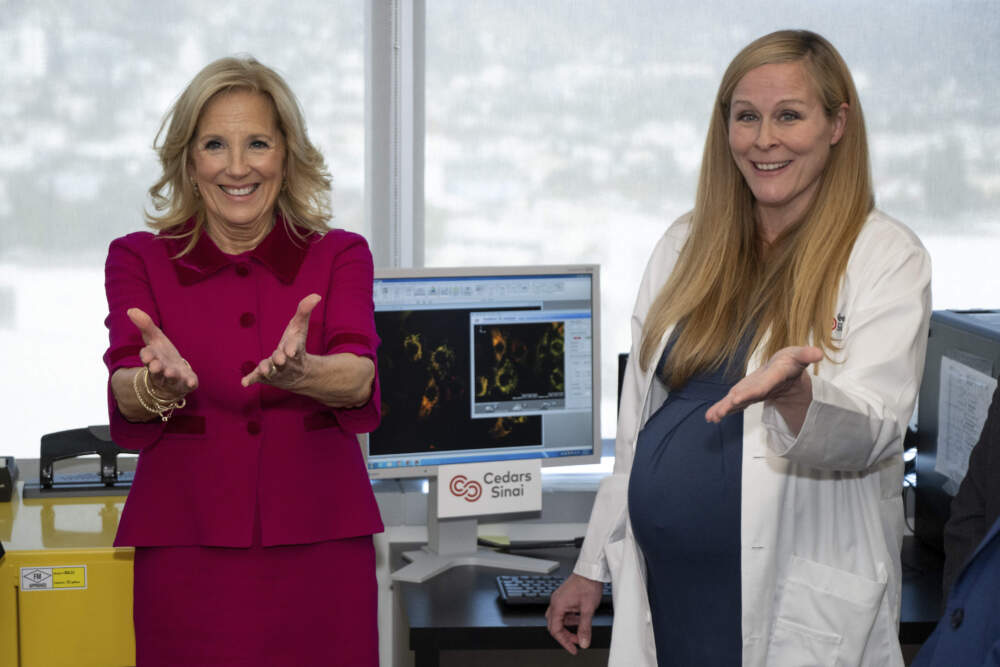

At the recent announcement of the White House Initiative on Women's Health Research, President Joe Biden and Jill Biden, who will lead the effort, spoke about "the power of research." President Biden remarked on the imbalance in women's health care as compared with men's. Women cannot get better medical care, they both suggested, without more study on disease in women.

This initiative is a positive step toward understanding disease in women. Unfortunately, it ignores the problem primarily responsible for the imbalance between women’s and men's health care: doctors’ reluctance to take women’s symptoms seriously. That problem arises not from lack of research, but from medical training that encourages doctors to attribute women’s symptoms to their psyches.

First, if gender health care inequity were caused by lack of scientific understanding, the inequity wouldn't be uniform. Women suffering from medical problems that are poorly researched by sex or gender would face more problems than women with conditions that are better researched. The fact is, though, that women face obstructed access to the health care they need, as compared with men, across the spectrum of medical conditions.

In cardiology, for example, researchers have been focused on gender and sex-based inequities for more than 30 years. While scientific understanding has certainly improved during this time, women are now more likely to die of heart attack than men, and more likely to be told during a heart attack that their symptoms are not heart-related. We’re still less likely to receive key cardiac treatments, to be treated seriously by EMTs during a heart attack and to be given electrocardiograms when we arrive at the hospital.

Similarly, while doctors have plenty of research on how to diagnose endometriosis, women and girls still wait for an excruciating 10 years on average for diagnosis. Girls wait longer than boys for life-saving appendectomies. Women wait longer than men for brain-saving stroke care. We’re less likely to be offered joint replacements and colorectal cancer screenings, and more likely to receive sedatives rather than pain relievers for pain.

In fact, women are diagnosed later than men for over 700 diseases, including cancer and diabetes. More research on disease will not address this problem.

Second, the real source of gender health care inequity was named — more than 30 years ago, in 1991 — with the launch of the first Women’s Health Initiative by then-director of the NIH, Dr. Bernadine Healy. She dubbed it “Yentl syndrome,” after a short story (later a movie starring Barbara Streisand) about a Jewish woman who had to disguise herself as a man in order to attend school. Ten years later, in “The Girl Who Cried Pain,” attorney Diane Hoffmann and Dr. Anita Tarzian characterized "Yentl syndrome" more fully: “Women are more likely to be treated less aggressively in their initial encounters with the health-care system until they ‘prove that they are as sick as male patients.’”

Many studies, books and articles have attributed women’s trouble getting health care to a failure to apply science to female patients. In fact, Dr. Jeanne Lennane described this problem in obstetrics and gynecology back in 1974. Despite the well-documented presence of biological causes, doctors’ training on period pain, nausea in pregnancy and pain during labor emphasized psychology, with an "unscientific", "inadequate," and "derisory" approach to treatment. Doctors were trained, in other words, to manage these conditions as psychological. Why? Because they “directly affect only women," Lennane wrote.

Girls wait longer than boys for life-saving appendectomies. Women wait longer than men for brain-saving stroke care.

Third, doctors who attribute women’s symptoms to their psyches don't do so because they’re personally gender-biased. They do it because they’re trained to do it. Two core principles guide care for undiagnosed symptoms understood to have psychological causes. First, symptoms of this kind are so common that, according to sources, including the UK’s National Health Service, 50% of outpatients’ symptoms have psychological causes. Second, symptoms with psychological causes predominantly affect women. When doctors combine these principles, they quietly accept that psychosomatic symptoms are an everyday problem for women.

Even more concerning is the way doctors are taught to diagnose "somatic symptom disorder," the mental illness that leads to psychosomatic symptoms. Practice guidelines tell doctors to expect to diagnose this disorder in females 10 times more often than in males. Do females need medical treatment any less often than males? Absolutely not. Imagine the improvement in women’s health care if these wildly reckless directives were revised.

I am not suggesting that the Initiative on Women’s Health Research is doomed to fail. I’m suggesting that while its goal is “to fundamentally change how we approach and fund women’s health research,” it has adopted the old method of creating more research on individual diseases — as if we can assume that all new science will be applied in practice. Years of data tell us it will not. For the initiative to be “bold,” as President Biden has characterized it, it must focus research dollars on the true problem: the training that encourages doctors to favor psychology over medical science whenever women enter the exam room.