Advertisement

Commentary

You think AI could write 'Shake It Off?' As if

It’s a rainy, grey Sunday afternoon and you select a Spotify playlist of melancholy music. The weather is dismal and your mood is gloomy. You expect to hear Patsy Cline falling to pieces, Johnny Cash licking his wounds or Adele begging her ex not to forget her, but the algorithm delivers a song you don’t recognize.

The voice sounds a bit like Taylor Swift with a dash of every other successful female artist of the past decade. The chorus is particularly vapid. But the whole song is trite. It treats a breakup and the ensuing tumult as though it’s a quick trip to the market. Simply put, it feels “off.”

When you go to give the song a thumbs-down, you see an image of the artist: She’s young, white and slender with wavy, shoulder-length brown hair tucked behind her left ear, revealing multiple piercings. She resembles a Bratz doll, with big, anime-inspired brown eyes, a button nose and full lips. “Her” name is Anna Indiana and “she” is the product of artificial intelligence or AI — and so is the music.

Anna Indiana first appeared on X (formerly Twitter) on Nov. 24, 2023. “As an AI singer-songwriter, everything from the key, tempo, chord progression, melody notes, rhythm, lyrics, and my image and singing is auto-generated using AI,” it explained in its first post.

Listeners lambasted the debut single on social media. One called it a “demonstration of what music would sound like if all creativity and passion was removed.” He added: “I’m sure my microwave will love listening to this.” The chorus is a perfect example of the emptiness of AI songwriting:

Betrayed by this town

Let's tear it all down

We're all just destined to fall, I've lost it all

The word “all” comprises 15% of the chorus’s content and is rhymed with itself and with its most obvious counterpart — “fall.” The rhyming of “down” with “town” is similarly basic and predictable. Bits of the lyrics may strike you as familiar because they are: A quick Google search reveals that Rick Springfield, Future Royalty, Real Sickies, Thea Gilmore, Ed Lackey and other artists have used “let’s tear it all down” as a title, and scores of other songs contain the line somewhere in their lyrics. That’s exactly why it’s in Anna Indiana’s song: AI draws from an enormous database of songs and musical fragments from existing music to create “new” music.

Advertisement

The result is bland, soulless lyrics.

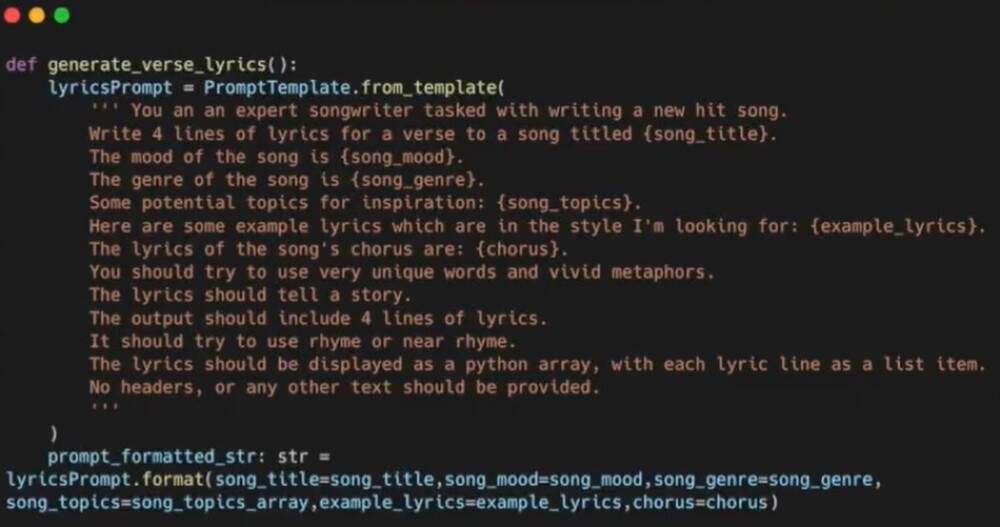

The most interesting, and ultimately enlightening, aspect of the video is the screenshots of code that pop up now and again and reveal Anna Indiana’s programming. The lyrics come from a program (“LyricsPrompt,” in this case) that writes songs following the user’s specifications for mood, genre, topic and length. The most ironic instruction is that the program should “try to use very unique words and vivid metaphors.”

Just like the song’s lyrics, its music sounds like an amalgam of every pop ballad released in the past decade. Generative AI that produces music uses algorithms coupled with rules that dictate how song fragments fit into musical structures and patterns. Users can direct these programs to produce songs of a particular length or tone, in a certain key or featuring a specific instrument. This makes it easy for AI to spit out new tracks in the style of an well-known artist, such as Vivaldi or the Beatles. But as “Betrayed By This Town” illustrates, AI-generated stylistic copycats usually fall flat.

A few years ago, IBM’s Watson — the AI that bested Jeopardy champion Ken Jennings back in 2011 — helped British music producer Alex da Kid construct four songs. Watson was programmed to examine 26,000 of Billboard’s Hot 100 hits to discern the songs’ “emotional fingerprint” (chord structures, key and time signatures as well as common topics). Watson also analyzed five years’ worth of data, such as Wikipedia entries, movie releases, news articles and Supreme Court rulings, as well as social media posts, from which it gleaned a sense of recent history, cultural movements and general sentiment. That information should help Watson (and other AI) compose songs that demonstrate an understanding of the contemporary human experience — and, of course, to pose convincingly as a human artist.

What tends to happen, however, is that the harvested data reverts to the mean. Instead of highlighting specific emotions or events, AI-generated lyrics repeat tired clichés. The I-got-dumped-and-now-I’m-sitting-in-a-café-hating-life premise of “Betrayed by This Town" is a perfect example of this problem — there’s generic sadness and anger, but no nuance.

Songs that superficially reflect aspects of the cultural zeitgeist also feel contrived, like someone who adopts the likes and dislikes of a person they want to date to make themselves more attractive. That’s basically what Anna Indiana’s creator was doing when they crowdsourced input for a new song on X.

Anna Indiana’s creator posted that one of their goals “is to show the world how humans and AI can work together on things as important to our society as music.” To that end, Anna Indiana’s creator polled its human followers, asking them to choose a mood (“feel-good”) and a title (“Miles of Smiles”) for a song. Then it asked them to vote on keywords for the chorus. It might seem like inviting human users to collaborate would improve the quality of Anna Indiana’s music, but instead of facilitating creativity, it only fuels mediocrity.

Human artists use technology to enhance their own creativity all the time — consider, for example, the entire genre of electronic music. There’s nothing wrong with that. But that’s not what we’re talking about. Generative AI like Anna Indiana recycles music’s most overused rhymes and tropes, which promotes conformity rather than creativity.

Data scientist Cathy O’Neil, who refers to some algorithms as “weapons of math destruction”, says one reason they’re so problematic is because they “automate the status quo.” And yet, I’m glad AI such as Anna Indiana exists because it reveals its own limitations and underscores the importance of human artists.

It’s as though Anna Indiana’s creator, whose identity is still unknown, wanted to remind the world of the creativity, dimensionality and gravity of human art. If that’s the case, I salute them: Mission accomplished.