Advertisement

Commentary

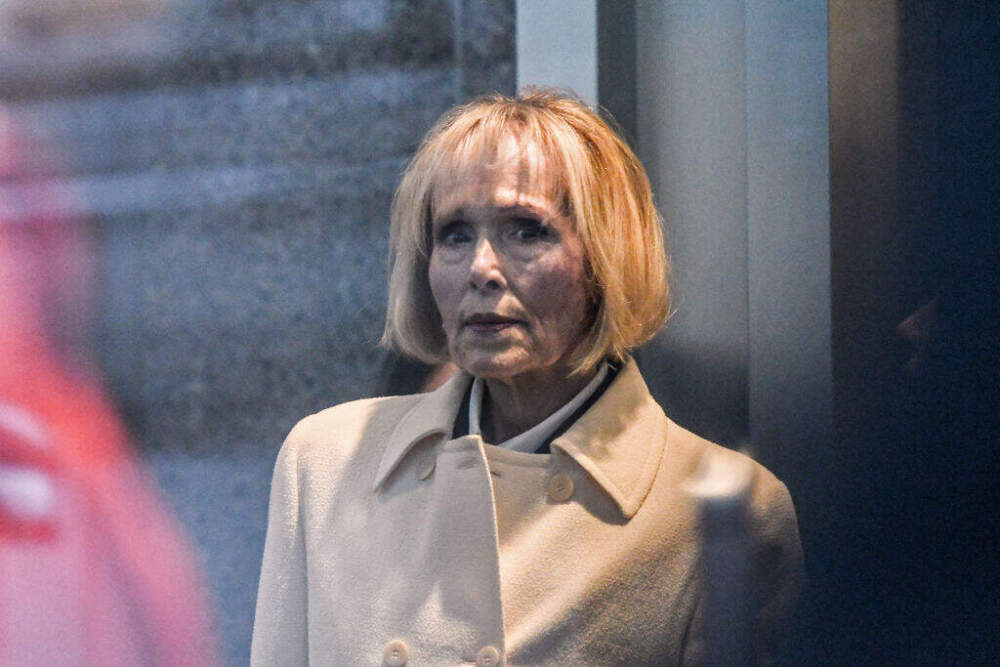

How E. Jean Carroll and an $83 million verdict finally got Trump to go quiet

Donald Trump, it turns out, can’t do whatever he wants. A Manhattan jury only took a few hours to award E. Jean Carroll $83 million for defaming her in the years since she accused him of sexual assault.

Most of the award, $65 million, was for punitive damages against Trump, who had already been found liable, in a civil trial last year, for sexually abusing Carroll. In this trial, Carroll’s lawyer had argued that Trump “doesn’t care about the law or truth but does care about money.”

She was right: Trump, who had recently made more than 40 insulting comments about Carroll in less than an hour, complained afterward about the verdict and the court. But he stopped attacking Carroll.

Why was Carroll, one of more than two dozen women who have accused Trump of sexual assault, able to hold him accountable for both assault and defamation?

Three factors converged: the #MeToo movement, the New York law that suspended the statute of limitations for survivors of sexual assault and Carroll’s determination to reclaim her reputation, career, life and her story by holding Trump responsible.

About two dozen women had previously accused Trump of sexual misconduct dating back to the 1970s. Although a few accusations of sexual abuse surfaced before Trump ran for president, the majority came after the “Access Hollywood” tape leaked in 2016. Trump notoriously bragged that “when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything ... Grab them by the pussy.”

His first wife Ivana Trump accused him of rape during their 1990 divorce (she later retracted her claim). Jill Harth accused him of “attempted rape” in 1993 at his Mar-a-Lago resort, but settled a separate breach of contract case and forfeited the rape claim. Jessica Leeds alleged that Trump attacked her on a flight to New York. Trump denied it all.

It took #MeToo’s outpouring of millions of women’s public stories to create a better understanding of sexual violence: what it looks like in real life, how pervasive it is and how it damages victim’s lives.

#MeToo made it possible to hear individual accounts previously dismissed as he said/she said — as part of the same story of sexual violence and impunity. The movement established a fairer baseline of credibility and created an expectation of legal accountability.

Before #MeToo, older rape victims like Carroll — 52 when Trump assaulted her, 80 now — were largely invisible and unheard.

The stories of the women who previously accused Trump were not that different from Carroll’s. She prevailed, in part, because #MeToo made us better listeners.

In 1996, when Trump sexually assaulted Carroll, she could not bring criminal charges against him. The statute of limitations for sexual assault in New York is three years and she later testified that it took her much longer to process the trauma of the assault.

For a long time, Carroll even had a hard time calling it “rape.” What Trump did, Carroll said, was an attack: “It hurt,” she said, when he forced his fingers in her vagina and curled them. This common response among survivors is documented in “I Never Called it Rape,” a 1998 book on sexual assault by Ms. magazine.

In 1996, myths about rape were common. When Carroll encountered Trump, he was a Manhattan playboy whom she had previously met. She was a 52-year-old respected journalist and witty advice columnist. She immediately told two friends after the attack, both of whom described it as rape.

Had Carroll filed a police report in Manhattan, it is unlikely Trump would have been charged. The district attorney at the time, Robert Morgenthau, prosecuted two high-profile rape cases, both of which made ample use of sexist and racist stereotypes to obscure facts (Robert Chambers, aka “the preppy killer” and the Central Park jogger case).

As a result of pressure from #MeToo, in 2022, the Adult Survivors Act, signed into law by Gov. Kathy Hochul in New York, suspended the long-elapsed statute of limitation for one year. It enabled victims of sexual assault to sue for damages.

Carroll had plenty to choose from, including Trump’s dismissal of her as a “nut job” and someone he wouldn’t rape because “This woman is not my type!” He called the rape allegations “a hoax and a lie.” (A jury last year found Trump liable for sexually abusing and defaming Carroll but did not find him liable for raping her.)

When Trump continued to defame her, riling up the MAGA mob to harass her, she sued him for defamation a second time. The same judge, Lewis Kaplan, presided. This time, the only question before the jury was defamation.

I have written about how sexual assault cases often come down to he said/she said. Typically, we have to take her word for what “he said.” In this case, we heard what “he said” in his own words. At his rallies and on Truth Social, even after he was found liable for sexually assaulting and defaming her, he couldn’t shut up about it.

We often say that “justice delayed is justice denied.” Justice for Carroll was delayed for over three decades. She lost her career, her reputation, and her sense of safety. She saw her earning power evaporate. She was menaced by the MAGA mob egged on by Trump.

The big story here, the one we should not miss, is how #MeToo continues to reverberate. It has made it possible for more survivors to tell their stories and for others to hear them. It has raised the expectation among attorneys that civil court is a place where victims can hold those who defame them liable. It has given those called to serve on juries a more realistic picture of sexual violence.

As much as #MeToo depends on silence-breaking, listening is the obvious and necessary corollary to addressing violence against women — in and beyond courts of law.