Advertisement

Commentary

Public trust in science is ebbing — and will have real-world consequences

Does it concern you to learn that nearly one in three Republicans and GOP-leaning independents believe that vaccines are more dangerous than the diseases they prevent? Or that only one in three Americans believes that human activity, such as burning fossil fuels, is a primary driver of global climate change?

Anti-science attitudes have historically encumbered societal progress in the U.S., often with serious ramifications. The teaching of creationism, which contradicts the established understanding of biological evolution, threatens scientific literacy and erodes the nation’s global competitiveness. Disinformation about vaccine safety sows fear and doubt, resulting in unnecessary deaths due to preventable diseases. Widespread denial of climate science hampers the nation’s development of public policies to curtail carbon emissions and prepare for future climate impacts.

Trust in scientific expertise has been ebbing since the pandemic. As the second Trump administration takes power this month, the emerging zeitgeist threatens to derail progress on climate change and other critical policy areas. It could also foster a shift toward autocracy.

Episodes of hostile skepticism throughout American history have punctuated public esteem for science, but science was ascendant in the era of the nation’s birth. Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke and David Hume, pioneers of empiricism and rational inquiry, strongly influenced America’s founders. To "promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts,” the U.S. Constitution mandated the establishment of the Patent Office. The first head of the patent office, Thomas Jefferson, was a polymath who conducted experiments with hybrid crops and farming techniques.

But it was also a time of witchcraft trials, entrenched superstition and folk medicine, such as blood-letting and treating syphilis with mercury. The practice of inoculation was called barbaric and irreligious in the early 18th century.

In the 19th century, advances in agriculture, transportation and communications boosted Americans’ faith in science. The development of railroads enabled westward expansion, and the telegraph connected distant cities for the first time. Thomas Edison’s electric light bulb illuminated homes and cities, and Charles Goodyear’s vulcanized rubber revolutionized manufacturing. In 1846, a Boston dentist started using ether as anesthesia.

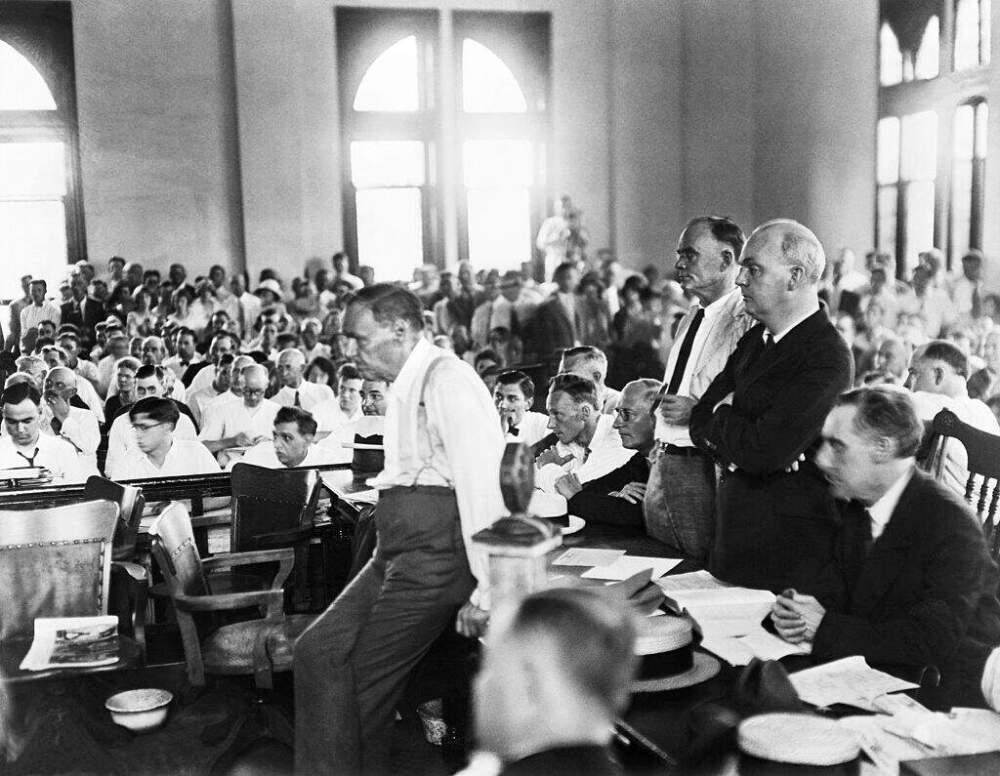

As science’s influence grew, it inevitably encroached on deeply held beliefs. When Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution arrived here just before the Civil War, its challenge to accepted beliefs about human creation was met with outrage. Protestant evangelicals called it “a threat to biblical truth and public morality,” and the Anti-Evolution League of America was active in several states. The issue came to a head in 1925 when school teacher John Scopes was prosecuted for violating Tennessee’s law that prohibited teaching evolution.

Advertisement

Opposition to Darwinism stemmed in part from religious objections, but American individualism and skepticism of authority fueled the controversy. Those who prided themselves on independent thinking “did their own research” and regarded scientific institutions with skepticism. The proliferation of pseudoscience — such as eugenics and orgone energy — further eroded society's respect for the rigor and reliability of genuine scientific inquiry.

In Boston, where I live, vaccination for smallpox mandated by the state government during the 1901-1903 outbreak was met with stiff resistance from the Anti–Compulsory Vaccination League. A challenge to the law allowing cities to require vaccination failed in the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the 20th century, landmark breakthroughs helped restore people’s confidence in the power of science and innovation. These milestones included the development of nuclear energy, the polio vaccine, antibiotics, the Green Revolution in agriculture, the space program, semiconductors and computers, and the mapping of the human genome.

The decades following World War II saw growing trust in scientific expertise as the public benefited from the advances it produced. But in the 21st century, respect for scientific knowledge has again declined.

An October 2023 poll said that only 47% of Republicans and Republican-leaning Americans believe science has a mostly positive effect on society. The scientific community is now bracing for potential upheaval as a new federal administration prepares to take office.

For example, the nomination of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to head the Department of Health and Human Services, which encompasses the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, raises the question of how the government would respond to another viral pandemic like COVID-19. Kennedy has been zealously opposed to vaccinating children against infectious diseases for over 20 years, despite his claims that he is “not anti-vaccine.” He has trafficked in numerous debunked conspiracy theories, including the narrative that the COVID-19 virus was designed to spare Ashkenazi Jews and Chinese.

Anti-vaccine propaganda has serious real-world consequences. Kennedy made a visit to the island nation of Samoa in 2019, where a measles epidemic that eventually killed dozens of children was tied to vaccine hesitancy. Officials said anti-vaccine activists took their cues from Kennedy.

Suppression of science is in the toolbox of autocrats.

The outlook for climate science is grimmer still. Climate journalist Emily Atkin laid out the case against Trump’s cabinet nominees, almost all of whom either deny the science of climate change outright or downplay the dangers of global warming. Several have deep ties to the fossil fuel industry.

Notably, The Wall Street Journal quotes Chris Wright, a fracking CEO and Trump’s nominee to head the Department of Energy, as saying that climate change would bring “probably almost as many positive changes as there are negative changes.” Wright is unlikely to embrace the scientific consensus on climate change or prioritize renewable energy and carbon reduction efforts.

Suppression of science is in the toolbox of autocrats. In 2019, Viktor Orbán restructured the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, moving 15 of its institutes under direct state control despite sharp protests in Hungary and other European countries. In the U.S., the Brennan Center for Justice notes that state governments have repeatedly dismissed, altered or suppressed sound scientific research that conflicted with their policy goals.

In The New York Times, M. Gessen writes, “Rejection of genuine expertise is both a precondition and a function of autocracy.” Autocratic leaders prefer to ally themselves with non-experts, marginalizing credentialed individuals who resist political aims. In George Orwell’s “1984,” one of the ruling party’s slogans is “Ignorance is Strength,” underscoring the idea that controlling factual awareness renders the public more malleable.

Science needs skepticism—it’s part of the scientific process. But skepticism is not the same as reflexive denial. Society must insist on evidence-based policies and resist the individuals who sidestep data out of self-interest. Only then can science guide us toward the common good.

Follow Cognoscenti on Facebook and Instagram. And sign up for our weekly newsletter.