Advertisement

Commentary

Farewell to Jimmy Carter, and a more innocent time

Jimmy Carter’s final moments on the worldwide stage this week remind me of his global debut in 1976, when he accepted his party’s nomination for president at the Democratic Convention at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

I was working in the newsroom at the Trenton Times in New Jersey when the editor, Richard Harwood, decided to send a cadre of what can only be called baby reporters, including me (a still green 27), to cover the event. For the paper, it was a cheap date, an hour away by train.

Having read “The Boys on the Bus” by Timothy Crouse, published in 1973 about the election of ’72 and the reporters — all men — who covered the candidates on the campaign trail, I knew the likelihood of a woman being asked to attend a convention was slim to none. Yet here was the chance to report on weighty matters. Like the precise level of the din when thousands of delegates surge to their feet to bat around a few beach balls and to sing “Happy Days are Here Again.”

What luck! An august assignment, at long last. Ha.

It was a moment of change and hope, that to me embodied, if not innocence, then seeming innocence, often the best we can do.

Outside the Garden, the usual flotilla of lost souls I’d grown used to was nowhere to be seen. Vanished: The woman who wore 10 coats no matter how hot it was, a man with a debris-filled beard cascading to his waist; another man, also generously bearded, shouting about how the end was nigh. Some bigwigs had decreed it a good idea to charge these homeless folks with vagrancy and ship them off to the hoosegow, to protect the sensitivities of the delegates as they filed into the arena along with the famous people, George McGovern, Ralph Nader and Tip O’Neill.

Boston-trained and old school, Tip took the longest, pausing to wave and shout a greeting at everyone he knew and at everyone he didn’t.

Carter was running against Gerry Ford, who had assumed the presidency when Nixon resigned after Watergate. A former football star from Michigan, Ford’s innate grace failed him when he somehow managed to tumble down the steps of Air Force One in full view of the press, inspiring the pundits to joke how about hard it must be to chew gum and walk at the same time. In New York, the cab drivers all offered the same tip-tailored spiel: “Gerald Ford is a good guy, couldn’t be nicer, but he’s pasta without tomato sauce and the country needs more spice.”

Advertisement

Associating Jimmy Carter with anything tangy was a stretch. He was plain, from Plains, Georgia, and he favored the kind of utilitarian sweaters made famous by Mr. Rogers. As his running mate, Carter chose Walter Mondale from Minnesota, whose nickname was Fritz. The ticket became known as Grits/Fritz which is about as spicy as it got. During some of the more dragged-out procedural aspects of the convention, the delegates proved that they could clap and sleep simultaneously.

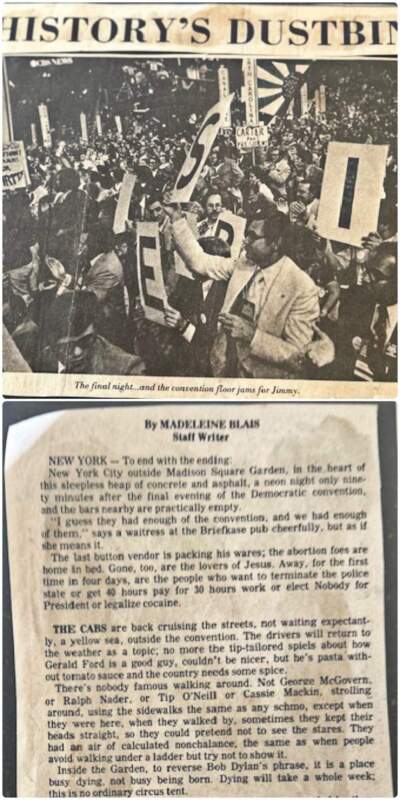

The outcome of Democratic Convention in ’76 was known before it began. It was a “unity” convention — and therefore lacked all suspense. When I entered the arena on the first of four increasingly dismal days in July, I was overwhelmed by immensity of the crowd — my memory tells me that were about 16,000 in attendance, but whether that number is accurate is not the point.

The point is that in the face of whatever quantity of humans filled all those seats, I could not figure out how to tell a single story in a singular way. All the delegates seemed to be waving the same signs, wearing the same banners, shouting the same slogans. Everything I wrote came out in knots. I felt like I was in a contest with an equally stymied colleague: Who could produce the most confusing lede with the most dependent clauses?

When the final benediction was given by Martin Luther King Sr., father of the slain civil rights hero, there was silence. When he said the Lord had sent Jimmy Carter to America to bring her back to where she belongs, there were shouts of “Yes, he did!” His loud tremulous “Amen” was the last official word of the gathering. I feared my sigh of relief sounded just as thunderous.

At that moment, inspiration struck. I decided I would stick around after everyone left and document the clean-up, the dirty dishes. I understood for the first time my own calling as a reporter: My beat would be the periphery, the aftermath, not the generals so much as the infantry.

Some people save love letters. I save old clips. As a result, I can quote exactly from the story published July 16, 1976 under the headline “History’s Dustbin.” I tried to capture a mood that has in more recent years been mocked. It was a moment of change and hope, that to me embodied, if not innocence, then seeming innocence, often the best we can do.

To end with the ending.

New York City, outside Madison Square Garden, in the heart of this sleepless heap of concrete and asphalt, a neon night only 90 minutes after the final evening of the Democratic convention, and the bars are practically empty.

“I guess they had enough of the convention, and we had enough of them,” says a waitress at the Briefcase Pub cheerfully, but as if she means it.

The last button vendor is packing his wares; the abortion foes are home in bed. Gone, too, are the lovers of Jesus. Away, for the first time in four days, are the people who want to terminate the police state or get 40 hours pay for 30 hours work or elect Nobody for President or legalize cocaine….

Inside the Garden, to reverse Bob Dylan’ phrase, it is a place busy dying, not busy being born. Dying will take a whole week. This is no ordinary circus tent.

Jimmy Carter is a prophet. Two hours ago, surrounded by thousands accepting his party’s nomination for the presidency, he said he sees an America on the move again. And he was right. There they are after Carter is gone. Americans on the move, two hundred laborers, electricians, carpenters and trash collectors, the men who will sweep up after history.

I watched the workers scramble to unscramble the wires of the phones. Some were missing, leading one worker to observe that the convention taught him something — there were petty thieves in all 50 states. A few of the delegates were refusing to leave.

“Let’s cross the floor one last time for posterity,” said one delegate from Ohio. They scrounged for souvenirs. A discarded name tag from Mayor Daley’s chair counted as a conquest.

It took two hours for a kind of lull to set in, the torpor we all recognize when a party has lost its steam.

The article ended:

The $2.2 million worth of security had dwindled to a few cops on the beat. The derelicts and the whores can come home now, if they want.

“Hail hail, the gang’s all gone.”

Of course, I could not know how the Carter presidency would play out with its ups and downs, the high interest rates, the hostages in Iran, the first solar panels on the White House, the overtures of peace in the Middle East. I had no idea how irritating the Washington establishment would find Carter when he turned down their dinner invitations, asked the military not to play “Hail, to the Chief” on the grounds that it elevated one individual above all others (before changing his mind out of deference for the musicians), and even ditched the Sequoia, a fancy government yacht known as the floating White House dedicated to posh parties on the Potomac.

Nor could I envision his extraordinary post-presidency in which he and his wife Rosalynn labored with such steadfast humility to support causes, especially ones related to mental health and to housing — literally nailing shingles on roofs to create homes for the homeless.

Nor would I realize that I would be creating my own time capsule of the week, one I would treasure forever.

Follow Cognoscenti on Facebook and Instagram. And sign up for our weekly newsletter.