Advertisement

After Bombs Hit, Spaulding Moved Front And Center

Resume

When the twin explosions hit the Boston Marathon last April, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital was 12 days away from moving into its new building at the Charlestown Navy Yard.

Among the first patients on Spaulding's move-in day were more than a dozen marathon survivors — some just released from acute care hospitals. They'd lost limbs, suffered burns and nerve damage, and some still had shrapnel embedded in their bodies.

"What happens in great places like Mass. General, they save people's lives that would have otherwise been lost. We like to say once they come to rehab we give the quality of life back after that life's been saved," said David Storto, president of the Spaulding Rehabilitation Network and Partners Continuing Care, which includes three other hospitals, as well as 23 satellite facilities.

"People just generally, at the onset of a significant disability, they're more concerned about the basic things in life," Storto said. "Are they going to be able to walk again? Are they going to be able to dress themselves again? Are they going to be able to brush their teeth again without being dependent, and requiring support of other people?"

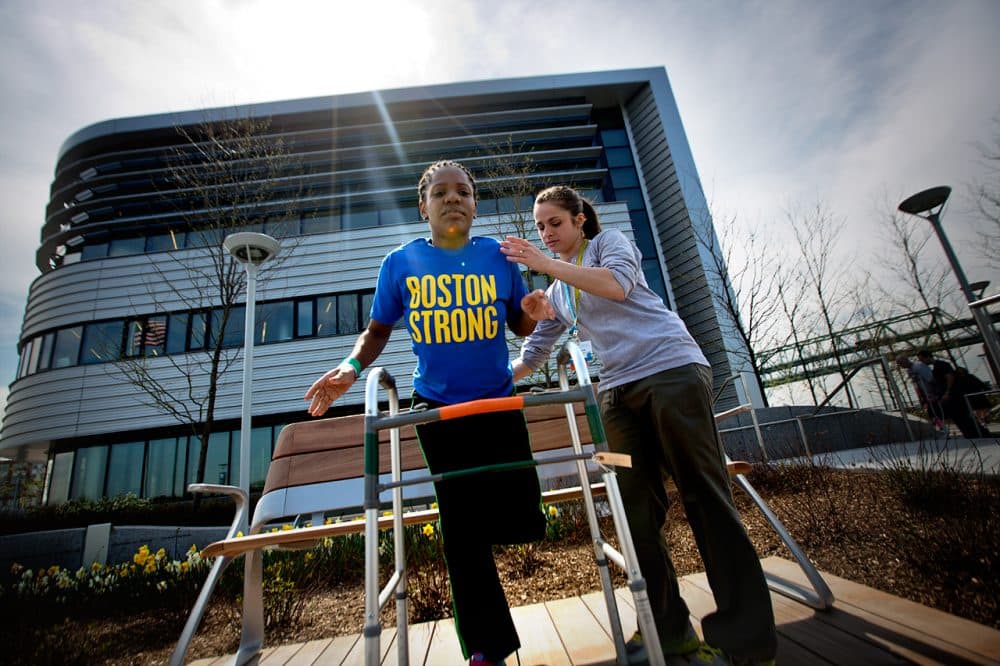

Thirty-two marathon survivors were treated on an inpatient basis at Spaulding, including 15 of the 16 who suffered amputations and had to learn to walk on prosthetic limbs. Among them: first-grader Jane Richard, the youngest of the marathon amputees; and Mery Daniel.

Daniel is a medical school graduate who was a spectator watching the runners at the finish line when the bombs went off. Her left leg was so badly damaged in the explosions, it had to be amputated above the knee. Doctors were able to save her right leg, even though some of the muscles had been blown away.

"When the doctors came in they were explaining all the damages and everything else that had happened, the only thing I could think, I'm glad I'm still alive, and that's what I'm looking for in life, living life to the fullest."

Now one year later, Daniel and all of the other amputees are working with prosthetic legs. Most of them are still receiving outpatient treatment at Spaulding or one of its satellite facilities.

'Rehab Out Of The Basement'

Spaulding's new $225 million hospital makes a statement.

Every patient room in the 132-bed structure comes with a view. Patients can lose themselves in thought looking out over Boston Harbor or the Mystic River — watching the giant ships roll in, small sailboats glide by, or airplanes ascending into the sky from Logan Airport.

Even the physical and occupational therapy rooms offer spectacular waterfront views.

Storto says the new building was designed to reflect how much rehab has changed over the years — no longer relegated to windowless rooms in the basements of hospitals.

"What we wanted to do when we built this hospital was make a bold statement about getting rehab out of the basement," he said, "and making sure that for the patients who are coming here, they had an environment and ambience that was most conducive to doing their rehab care."

But there was one design flaw, pointed out during a tour near the end of construction, by spinal cord injury patient advocate David Estrada.

"The first thing I noticed is that I couldn't see out the window," he said. "I'm sitting in a wheelchair, the wall was up to my, above my eyesight, head height. I said, 'Gee, you guys must really want people to work hard cause you can't see out the window.' "

The window sills were lowered at a cost of $300,000.

The nine-story building sits on reclaimed land, made possible with support of former Boston Mayor Thomas Menino. But it came at a cost.

"In terms of this site, it was so polluted, we paid $25 million to clean up this site," Storto said.

For the past eight years, Spaulding has recruited more than 100 individuals to run the Boston Marathon to raise money to support the work of the hospital.

"The marathon bombings and the needs of the survivors really did catapult Spaulding in particular into the limelight," Storto said, "and for all the wrong reasons gave us an opportunity to educate the public in ways we otherwise would not have had about the importance of rehabilitation, about issues of physical disability, and to have the public become more and more aware about just what the possibilities are for people to return to very, very gainful lives."

Storto himself is a marathoner, and he too will be running again this year — running for those who can't.