Advertisement

Strategy Flags Almost All Genetic Heart Disease Patients Who'll Face Sudden Death

Researchers at Tufts Medical Center report reassuring accuracy predicting which patients with a common genetic heart disease are at the most risk of sudden death and thus most need an implanted device that can shock their heart back into normal rhythm.

Their study looks back over 17 years at more than 2,000 patients treated for the disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy — a thickening of the heart muscle best known for killing young athletes in mid-game.

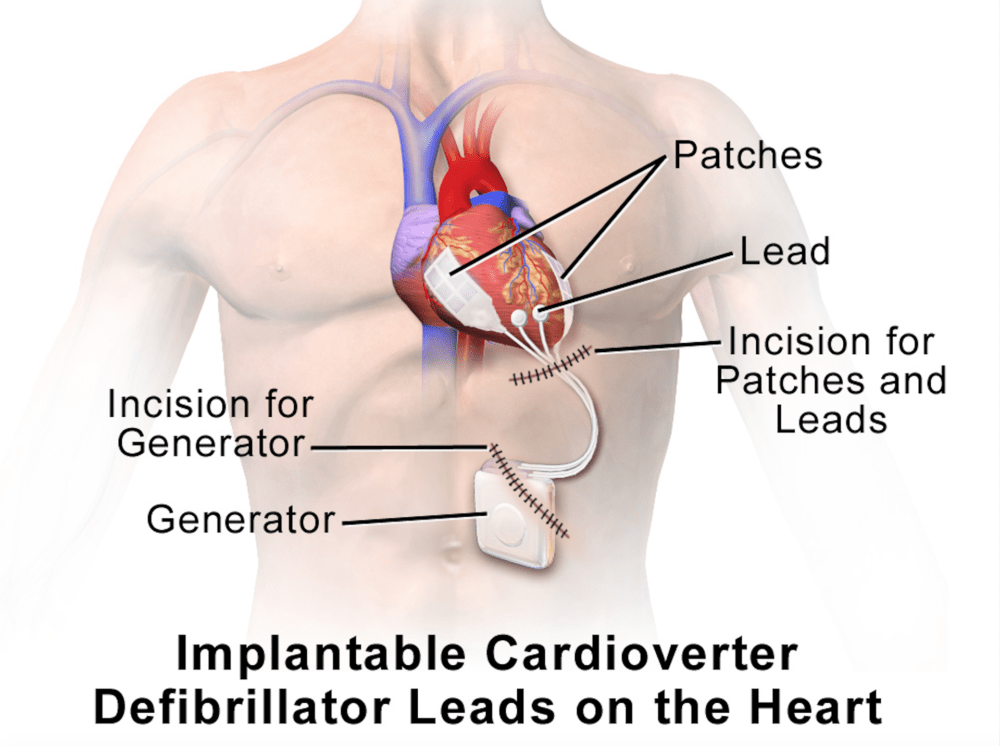

More than 500 patients were deemed to be at such high risk that they needed a lifelong device — an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, or ICD — implanted. The recommendations were based on family history, heart imaging and several other factors.

The study "identified 82 patients with this genetic heart disease, through this strategy, that had the ICD, that received a lifesaving shock at some point after their evaluation and their implant," says lead author Dr. Martin Maron, director of the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Center at Tufts.

In other words, it was a very good thing that these 82 patients had ICDs — they might have died without them.

The study also identified five disease-related deaths among the patients. Two of those patients had been told they needed the device but declined.

I spoke with Dr. Maron, and here is our conversation, lightly edited. He began with the background:

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or HCM, is the most common genetic heart disease in the world, and the leading cause of sudden cardiac death in young people in the United States, including competitive athletes.

We have a medical device called an ICD which has been shown to be effective at shocking patients with HCM out of potentially life-threatening arrhythmias that can occur in this disease.

However, accurately selecting which HCM patients need this ICD device, which is implanted in the patient for their lifetime, has been challenging, and which methods to use have been debatable.

So what we've done over the last 17 years at our national HCM referral center here at Tufts Medical Center is, through studies that we and others have done, to assemble a number of non-invasive risk markers. These markers are found in either the patient's history — their medical history and their family history — or are derived out of testing — imaging tests of their heart or monitoring of their heart rhythm over several days.

What we've done is then take these markers that have come out of the testing and unified them in a strategy with clear definitions and criteria.

What we recommended to patients was that if they had one or more of these major risk factor markers that it would be reasonable for them to consider the ICD implant.

So the present study, then, was done to assess the reliability of this sudden death prediction strategy using these markers within our dedicated center here at Tufts.

And what we showed is that, over 2,000 consecutive HCM patients, this strategy using these risk markers was highly effective for predicting which patients were really at the highest risk for these sudden death events.

Was this study a first or a "most"?

This was the largest prospective evaluation of a risk stratification strategy to prevent sudden death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the most common genetic heart disease. And the strategy has been shown to be highly effective in identifying almost all HCM patients that are at risk for life-threatening sudden death events.

The downside is that arguably, over 400 people got the device who didn't end up having a life-threatening event. So is that overtreatment?

I'd say two things. The average age that patients are identified as at risk for this disease is early 40s. So we're talking about patients who are young, with a genetic heart disease that puts them at risk for life-threatening rhythms for many decades of their lives.

And so to protect, and really to save, as many patients as possible, we accept a small amount — and we consider it a small amount — of overtreatment with the ICD in order to achieve the primary goal that we have for our patients, which is saving as many lives as possible.

And I suppose the response would be the same about the 15% or so who have device complications, that it's a price worth paying?

Correct.

And then there were the five patients who did have fatal cardiac events. Two of them were told to get the devices but declined. But what about the other three? Do they suggest that you need even more refining?

I think what that says is that we know that it's not yet a completely perfect strategy. It's highly effective, and much more effective than anything we've had before. But that doesn't mean that we're done, and that there can't be room to continue to refine even what we've done here, to hopefully, in the future, maybe identify literally everyone who's at risk.

You came pretty close.

Yes. That's why it's important. And the point we wanted to make is that this is a clear, concise and relatively simple strategy that we believe can be replicated by all practicing clinical cardiologists, with the hope that these results can therefore be used to really save HCM patient lives anywhere in the world. That's the goal.