Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

The Surge: WBUR's Virtual Town Hall Tackles Your Questions About COVID-19

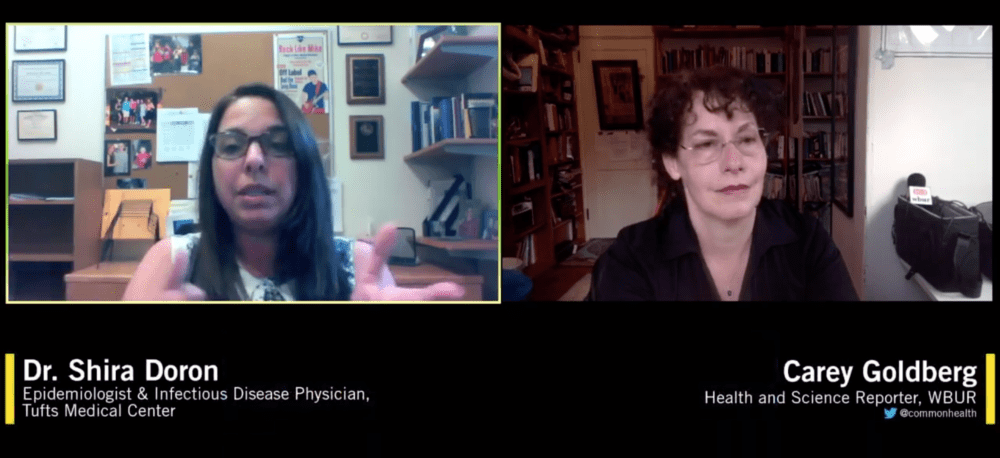

As Boston braces for what may be the worst week for COVID-19 cases, WBUR reporter Carey Goldberg interviewed Dr. Shira Doron, epidemiologist and infectious disease physician at Tufts Medical Center, and asked questions submitted by the public about the challenges facing the commonwealth and all of us.

Watch The Full Virtual Town Hall

Interview Highlights

On the surge of COVID-19 cases in Massachusetts and how Tufts Medical Center is faring:

So the number of COVID cases and specifically COVID hospitalizations in Massachusetts are continuing to rise. Many hospitals have reached — or are getting very close to what they would consider to be — their capacity, as a tertiary care hospital, which generally gets a substantial proportion of its admissions as transfers from other hospitals. And because no one has yet [become] an expert in COVID care, we were really slower to fill than some of our neighboring institutions and our community affiliates.

But once they filled up, our admissions started going up quickly because we started taking those transfers. So we have doubled the number of covered cases that we had last week and significantly more than we had yesterday, replacing critical care patients in areas normally used for non-critical patients. We have adults being managed in the pediatric ICU by our amazing pediatric intensive care docs.

...[Tufts has] capacity, as I said, and we've moved into contingencies sort of areas, but we are...in the surge.

Advertisement

And with the numbers still rising, at least from where I sit, we've not yet peaked. So the question of whether the system will become overwhelmed, whether we'll have enough ventilators, whether we'll have to make those horrible decisions that we hope to never have to make, like who gets a ventilator and who doesn't, that has yet to be answered. And we've had more time to prepare than Italy and New York. We have the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center open and the DCU open and Worcester ... Those are open now, before we even need them, already taking patients before we're at capacity. The state has been receiving more ventilators, we're as prepared as we can be. But, as I said, certain supplies are running dry. And that puts our health care workforce and patients in danger.

On contract tracing:

There are two stages in the response to a pandemic: containment and mitigation. During the containment phase, you're trying to detect every single case, isolate that person while they're contagious, find all of their contacts — that's people who were exposed to them who could be incubating the virus are already sick. That's contact tracing, and [you] quarantine them so they don't become contagious and infect anyone else. For this pandemic, though, we were hindered in our ability to contain the virus using contact tracing by the lack of widespread testing.

As I mentioned, we weren't able to detect the cases in order to contain them. And we've now reached a stage where the number of new cases each day is so enormous that it would be prohibitive, from a human resource standpoint, to call them all on the phone and all their contacts ... For this infection, so many of the positive cases that we're detecting — especially in employees [of the hospital] — are so mildly ill that they're going about their regular lives for days upon days before they even think to get tested. So the numbers of contacts are really large. So, that's in part what brought us to this mitigation phase, which sort of took us out of the containment phase and puts us into the mitigation phase ...

The mitigation phase is where you use the social distancing measures to minimize the damage, to flatten the curve, as they say. So you don't get such a large number of people sick all at once that the hospitals can't handle them and treat them and keep them alive. The hope is that when we're on the other side of the peak, we could actually get back to the containment phase.

And so, unique to Massachusetts is this initiative called [the] Contact Tracing Collaborative that's enlisted hundreds of people to perform contact tracing in an attempt to establish containment. And it may seem impossible now, but as the numbers hopefully decline again, it may become more realistic ...

On social distancing and the future:

Very smart people have built mathematical models designed to predict where we're headed, but models are based on assumptions and there are a lot of assumptions still being made. We don't really know how well people are adhering to social distancing in their day-to-day lives.

We don't really know what percent of the population is sick now or has already recovered from the disease. We know from the influenza pandemic of 1918 that it is quite possible for cases to spike again after distancing measures are lifted. Right now, all eyes are on Wuhan as the canary in the coal mine since they're just starting to open up.

On personally avoiding the virus:

Well, I leave my shoes at the door. I clean my hands a lot. I wipe my phone with disinfectant. And not necessarily every day. I don't clean the mail or the grocery bags or the outside of the takeout containers, but I do clean my hands often as I handle those things. I try not to touch door handles or elevator buttons, and if I do, I definitely don't touch my face until I clean my hands. And try not to let the worry over the disease consume me. I've got enough to worry about here at the hospital ...

I think what everyone's got to find their own balance of being obsessive and, you know, being a little bit less so. I clean my hands and I try not to touch my face. And so, if I've touched the grocery bags but I've cleaned my hands, then that should do it.

On false-negative COVID-19 tests:

Well, I can tell you that the issue of false negative tests is certainly being discussed by health care professionals. We're very concerned about labeling somebody negative and having them go out and expose people ...

The problem is this; In order to know what percent of results of a certain type of test are false negative, you have to have something to compare it to that's better than the test you're evaluating. And to know how sensitive your new test is, you actually need to have something called a "gold standard." But the tests that we're using ... [are] very, very sensitive. It actually detects minuscule quantities of virus in the sample.

Nevertheless, we see a few things that make us wonder if we're experiencing these false negatives. So we see patients who have all the classic signs and symptoms of COVID, but the test is negative. We also see patients who test negative and then we continue to have a high suspicion that they have COVID and we repeat the test and they test positive. And that makes us worry about the test.

So there are a number of possible explanations for this. One is the technique with which the sample was taken. Now, I think most people have heard that the way that the sample is taken is a swab ... and so there's a possibility that the swab isn't done right ... you didn't get secretions, that you didn't get cells. And that could be why the test is negative, which should be positive. Or it's possible that the patient just doesn't have COVID.

You know, there was some suggestion that as we were heading into this cold season, we were actually starting to experience some pretty bad mycoplasma season. Mycoplasma is a bacteria that causes walking pneumonia. So, you know, maybe these patients don't have COVID and it's not a false negative test. But basically, this should be added to the long list of things we're really trying hard to learn more about.

On prospects of a COVID-19 vaccine:

I do worry that a lot of people, including sometimes myself, are putting all their faith in a vaccine as a way to get back to normal. Vaccines typically take at least 10 years to bring to market, and 90% of candidates fail for one reason or another. We've been told that the process is being fast-tracked. I fear that we may be being overly optimistic. This virus is probably here to stay. And what exactly that looks like in terms of our personal freedoms over the next few years is really anyone's guess at this point.