Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

'Drinking From A Firehose': Tapped As The Rule Enforcers, Local Health Depts. Brace For Reopening Calls

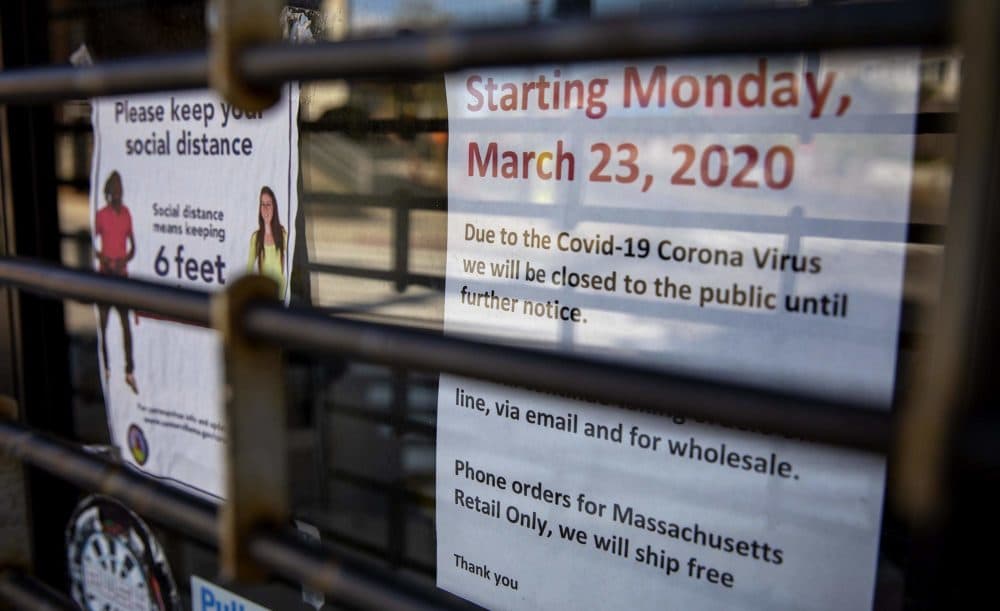

Starting Monday, thousands of previously shuttered businesses will have the go-ahead to reopen — with lots of new COVID-19 related rules and restrictions.

The state wants all businesses and workers — from hair salons to office spaces, to pet groomers and car washes — to practice social distancing, sanitizing and mask-wearing. The agency responsible, in large part, for ensuring they comply with all the rules? Your local health department.

“We’re worried,” says Cheryl Sbarra, senior staff attorney and director of policy and law for the Massachusetts Association of Health Boards. “And maybe, hopefully, we’re worried unnecessarily. But I’m not sure that we are. Because when you look at what's happened in other states when they've opened, we know there will be surges.”

Gov. Charlie Baker’s reopening order says businesses must come up with a written “COVID-19 Control Plan” covering how the workplace will prevent the spread of the virus. Those businesses also need to meet the mandatory standards and sector-specific protocols published by the state.

But they aren’t required to file those plans anywhere, and because of how many businesses will reopen all at once, there won’t be much proactive inspection. Instead, it will be up to a customer or a worker to call their local health department or the state to report problems.

Rules That Keep Changing

Even with state help, local health department employees expect to be inundated with calls, as they have been for the two months since the non-essential business order went into effect. Some are operating with just a few full-time workers.

“We've already seen an uptick in calls just about the essential businesses that have been operating this whole time,” says Jacquelyn Murphy, director of public health in the central Mass. suburb of Milford. “So I think it would be unexpected if we didn't have even more calls when things start to reopen.”

“We’re worried. And maybe, hopefully, we’re worried unnecessarily. But I’m not sure that we are."

Cheryl Sbarra

Murphy, who started her job in September, says the workload has been like “drinking from a firehose” for the department’s three full-time and two part-time staffers.

That’s been in part due to frequently shifting guidelines. Sigalle Reiss is the public health director in Norwood and the president of the Massachusetts Health Officer Association. She understands why the rules have to change as what is known about the coronavirus changes. But that fact doesn’t make the situation any easier to enforce.

“From an enforcement standpoint and in a policy-implementing standpoint, it's very, very difficult to have this constant changing environment,” she explains. “Not only the confusion, but also for us planning as a municipality. You know how we move forward. It's just as difficult for us as it is for the businesses.”

And with four phases of reopening — and all on yet uncertain timelines — things are expected to get more confusing.

Advertisement

“Reopening is going to be even harder,” Reiss says. “Maybe the hardest part for us through this process.”

In western Mass., Randy Crochier has experienced that whiplash as he responds to complaints across his extremely rural health district. Crosier is the regional health agent for the Franklin Cooperative Public Health Service, which covers 11 towns that range in size from 2,000 to 300 people.

A few weeks ago, he got an anonymous complaint about a factory continuing to manufacture and ship, against the rules at the time. Crochier went out there and talked to a manager, who shut operations down.

“Ironically enough, that day the governor signed a loosening of the regulations,” Crochier says. “The governor signed regulations allowing for those types of operations to resume remote fulfillment. So I was able to contact the person I was in touch with and say, ‘Hey, you can go back to shipping. You just can’t make [anything].’”

But even Crochier, who is the only full-time health agent for a district that takes 90 minutes to drive across, says it makes sense that this kind of enforcement falls on the locals like him.

“Is it difficult? Yeah,” he says. “But it makes sense.”

“I believe that our 11 towns, for complaint-driven things, our 11 towns will be OK,” he adds.

Education, Not Punishment

The 351 local health boards across Massachusetts all have varying resources and needs. Sbarra worries about inequities: Will there be workers who don’t feel safe enough at their job to flag a concern. And will some cities and towns be better equipped to respond to those calls?

“We need to find a way to operate our local public health system in a way where it doesn't matter what zip code you live in,” she says. “You are entitled to and you receive the same level of services. Everyone should be receiving the same level of public health services. And that's not happening now.”

“Reopening is going to be even harder. Maybe the hardest part for us through this process.”

Sigalle Reiss

Desperate for help, local health agents have pulled people off their regular jobs and into dealing with the pandemic. Food inspectors, recycling coordinators and administrative assistants are now fielding complaints, too. Duties that would have picked up around now — pool and beach inspections, septic tank installation checks — are put on the back burner.

And health officials say they’re willing to rely on their police forces, too, though they don’t want to have to use the arm of the law to convince people to follow the rules.

“You always start with education,” Reiss says. “And a lot of times it's just that people didn't understand. Most people are compliant. Most people want to do the right thing. And of course, you're going to get people that aren't compliant and are knowingly going against the orders or guidelines.”

That’s where police, or warnings and fines might come in. There are four levels of enforcement: a “verbal consultation and redirection,” a written redirection, a $300 fine and, most severely, a cease and desist letter.

But public health officials say they don’t want to have to go there. They hope a gentle explanation of why the rules on wearing a mask or keeping social distance are important will be enough.

Resources: The Department of Labor Standards has a hotline for complaints about businesses that may not be meeting the COVID-19 safety standards at: 508-616-0461, ext. 9488, or by sending an email to safepublicworkplacemailbox@mass.gov. Attorney General Maura Healey says her office is also taking complaints from workers at 617-727-3465 or at this website. Concerned customers or workers can also call their local board of health.

This article was originally published on May 25, 2020.

This segment aired on May 26, 2020.