Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

How A Science Giant Pivoted To Coronavirus Testing And Helped New England Colleges Salvage On-Campus Fall

With its cream-colored walls and low-slung profile, the building at 320 Charles Street in East Cambridge is so nondescript you might not even notice it as you pass by.

But if it's late in the afternoon, you may well notice the parade of drivers pulling up every few minutes to the curb in front, and bringing coolers and cartons and Styrofoam boxes inside.

Some are professional delivery people, like medical courier Brendyn Anderson. "I probably come here maybe like seven or eight times a day," he said. "Today I came here about eight times, just because we had a really big influx of samples today."

Some are college staffers like Joyce Maudie, the softball team coach and assistant athletic director at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island. "Every day, we bring about a thousand tests up here," she said, "so that we can get it turned around in 24 hours and make sure our students and faculty and staff are safe, and we're doing our part."

Add up all the deliveries, and you get more than 70,000 coronavirus tests a day, being processed at the Charles Street building, which belongs to the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

At latest count, the Broad has performed a total of nearly 3 million coronavirus tests. At 70,000 a day, it alone is running about 7% of the national total of about 1 million tests per day. It's handling the tests for Massachusetts nursing homes and hot spots, and over 100 colleges.

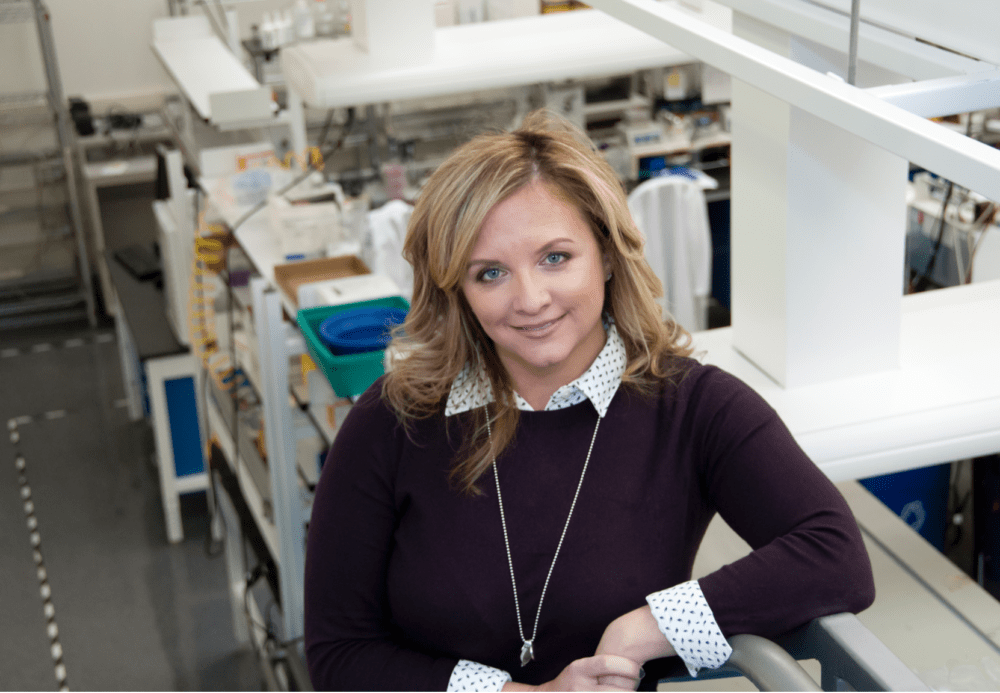

The goal is to hit over 100,000 tests a day soon, said Stacey Gabriel, who oversees all the testing. The ramp-up is challenging, she said, but it's working.

"I think we’re all learning a lot, together with our users," she said. "None of this has been done before. College campuses have never ordered thousands of diagnostic tests for their students every day before."

And the Broad has never tested millions of samples for viruses before.

The institute is known as a powerhouse of the young science of genomics — DNA research seeking to understand diseases like schizophrenia and cancer. Its building at 320 Charles houses its collection of machines for analyzing DNA, believed to be the biggest in the country. Normally, they’re used almost entirely for research.

Advertisement

But this March was anything but normal.

"Testing just wasn’t there as we needed it," said Dr. Deborah Hung, a leading researcher at the Broad and an infectious disease doctor at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

As the pandemic was just starting to hit in Boston, she had a very frustrating time arranging a test for a patient. "I can say that it consumed probably almost 12 hours to make things happen," she said. "Twelve continuous hours of my making phone calls."

On the morning of March 9, Hung ran into her colleague, Michael Mina, an expert on diagnostic testing. She’d just heard him talk about the need for more coronavirus testing in a radio interview, and the two discussed what it would take to do large-scale testing: high-throughput robotics. Expertise handling the samples. And a certified lab that could do the type of tests needed.

"And when you think about it that way, there are not that many institutions where all of those converge," Hung said. "And so I would say, literally it was two seconds to click."

From her car, Hung called Gabriel at the Broad Genomics Platform, to broach the idea of using its DNA machines for coronavirus testing.

'It Was All A Leap Of Faith'

"My next phone call was to Eric, knowing that he had to approve, essentially, what I was proposing," Hung said.

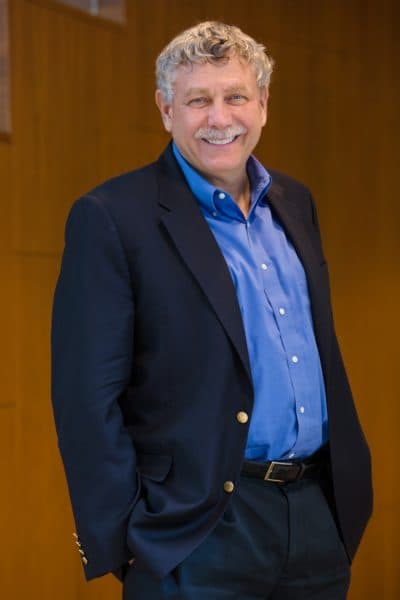

That would be Eric Lander, president of the Broad and its leader since it was founded in 2003.

"There really wasn’t a choice," Lander recalled. "Deb Hung called up and she was so adamant: ‘You have to do this, you have to let Stacey do this,’ she told me. And I really didn’t have a choice. I said, ‘Of course.’"

He figured Gabriel and her team were already running a top DNA analysis center, "and they knew how to take any process and make it automated and efficient and inexpensive," Lander said. "And so all I had to do was say yes, and basically over a three-day weekend they came back with a plan for doing high-throughput COVID testing."

And the complex conversion to mass coronavirus testing began, even though it wasn’t clear yet how bad the pandemic would get, Hung said.

"There are not many institutions where I could pick up the phone, make two phone calls, based simply on my personal assessment, and have people mobilize and say, ‘Let’s evaluate this,’ and then really rapidly say, ‘Let’s just do this.’" she said. "It was all a leap of faith."

In April, as COVID-19 cases and deaths mounted, the institute was running over a thousand tests a day from nursing homes, homeless shelters and hospitals. At first, many samples were messy.

"We were receiving tubes that were leaking and sometimes floating in water from ice packs, and wet paper that was really hard to read," Gabriel said.

To scale up, her team had to put a better system in place. They did.

These days, "Those tubes come in a very standardized way," Gabriel said. "It’s very clean. There’s a bar-code. There’s an automated flow of information. And it has just been enabling."

The testing facility runs 24/7. It has brought on more than 200 new employees since May and is still hiring, she said — especially for the night shift.

Meticulous Attention To Detail

Other DNA research centers around the country have stepped up to help with testing, from Baylor College of Medicine in Houston to the University of California, Davis.

Such centers are not typical academic research labs, said Dr. Eric Green, the director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, which funds some research at these centers.

"They are mini-factories that happen to be residing at academic research facilities, and that’s key," he said. "And it’s both the infrastructure, but it is also this meticulous attention to every aspect of the process, from samples coming in the door to data going out on the Internet."

Among them, the Broad’s testing effort is by far the biggest, he said. Green calls it "Lander-esque" — a reference to Eric Lander, a fellow human genome pioneer.

"Eric always, to his credit, is going to tackle it at a scale that nobody else is quite ready to do," Green said. "The Broad really went all-in, in a very aggressive way."

And the testing capacity it built is now allowing thousands of college students to be on campus across the region. Again, a phone call was key.

In May, a group of Massachusetts college leaders approached the Broad. They’d concluded that the only way they could bring students back to their campuses was if they could test them — a lot.

"We gave Eric a call, and the rest, as they say, is history," said Dr. Paula Johnson, the president of Wellesley College, who helped lead the group's thinking on testing.

They set up a program that could be used by a wide range of public and private institutions, she said. The Broad is a nonprofit and provides the testing at cost, about $25 a test.

"This is not a money making venture; this is a public service," Johnson said. "We wouldn’t be able to do this without the Broad."

As Long As It's Necessary

The institute agreed to run tests for colleges in Massachusetts and to a lesser extent around New England, and it currently has a waiting list of out-of-state colleges.

The program's success, Lander said, signals "what the future of the country has to be. To meet any of the challenges ahead, it's got to be science-based pulling together."

Some Massachusetts parents are now pushing for the Broad to offer testing for public K-12 schools as well, and the institute is also working with employers who want to use testing to help bring workers back.

Still, mass testing is not what the Broad institute is really for.

"I’m viewing their role as short-term first responders," said Eric Green from the National Human Genome Research Institute. The Broad was positioned to help in a crisis, he said, but its mission is research.

So how long will it keep doing all this testing?

"As long as necessary," Lander said, "which we hope is very short."

This article was originally published on October 02, 2020.

This segment aired on October 2, 2020.