Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

The World Hopes A Coronavirus Vaccine Will Come To The Rescue. Some Scientists Aren't So Sure

Resume

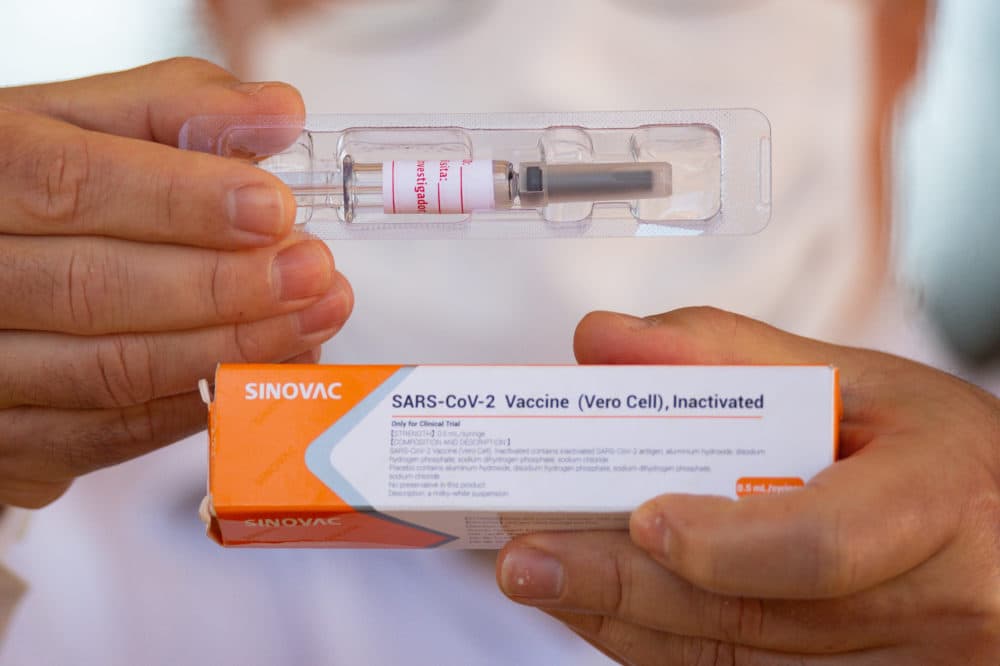

Pandemic-weary residents everywhere are holding their breath for the first coronavirus vaccines to be approved by federal regulators. The shots, currently being mass produced for international distribution, carry with them the hope of putting an end to the COVID-19 pandemic and resuscitating the global economy.

But Dr. Marc Hellerstein, a vaccine researcher and toxicologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who studied at MIT, says he isn’t actually sure if he'll take one of these early vaccines.

“That’s a really good question. I might,” he muses. “I’d be worried though. I’d be worried about – do I have to get another vaccine in two years?”

Hellerstein is one of a small but vocal contingent of scientists that are warily watching the development of the coronavirus vaccine frontrunners. In general, they have two theoretical concerns about the first candidates, which could receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration sometime within the next year.

First, these vaccines focus primarily on creating antibodies – immune defense compounds that can neutralize the virus. Hellerstein says that might mean the vaccine’s protection is short-lived.

“This is what scares me – say you give some people a vaccine, and it just gets antibodies. A year later, they’re dying away because that’s how long these antibodies live. Six months, even less,” Hellerstein says.

Once those antibodies fade, Hellerstein says it’s unclear if the immune system will still recognize the coronavirus and mount a strong defense. Antibody levels often wane after the body recovers from an illness, but the immune system can typically create those antibodies again quickly if the same pathogen returns. Even so, Hellerstein argues a vaccine that focuses on T cells, a type of white blood cell that helps fight infections, might be more lasting.

In Hellerstein’s own research, he found that T cells created by the yellow fever vaccine were still effective decades after the vaccine was injected. And, Hellerstein adds, when researchers looked at people who had recovered from COVID-19, they found those who had only mild illness had fewer antibodies but more T cells. Hellerstein thinks that might mean T cells are more important for fighting off COVID than antibodies.

“The people with mild infection often don’t have antibodies at all. Those are the people we want to emulate. They won. They succeeded,” Hellerstein says.

Those people also created many different T cells that targeted different parts of the coronavirus, but the leading vaccine candidates provide the body with only one of those targets – the spike protein. This is the tool the coronavirus uses to infect and enter cells.

“I would say it’s five different flavors of vanilla,” says Dr. Anne De Groot, the co-founder of a vaccine design firm called EpiVax. “The problem being that if the spike doesn’t work [in a vaccine], then what do you have?”

Like Hellerstein, she has doubts about the leading vaccine candidates – especially what she considers an overcommitment to the spike protein. If vaccines based on this protein fail to provide adequate protection against the coronavirus, then the millions of doses that companies have already manufactured will end up in the incinerator. De Groot says that result would be disastrous for public health and could hinder subsequent efforts for a better vaccine.

“I think that’s going to have a hugely damaging effect on public trust in vaccines. So, we really need to have a plan B,” she says.

De Groot says that plan B should include the development of vaccines that focus on different targets and use a variety of strategies in case one fails, or the coronavirus mutates in a way that makes the leading vaccines obsolete. Recently, a mutation was found on the spike protein in coronavirus cases in Denmark, although it’s unclear if that mutation will affect the vaccines’ effectiveness.

Creating more vaccines that focus on other parts of the virus or increasing the complexity of the existing vaccines would also stretch out development time. That’s time we don’t have, points out Dr. Daniel Barouch, a vaccine researcher at Harvard University. He also led the team that designed the Johnson & Johnson coronavirus vaccine now undergoing clinical trials.

“It gets exponentially more complicated to add additional components,” Barouch says. “If you had 10 years, could you make a better vaccine? Probably. In terms of what could be done within the space of a year? Then I think this suite of vaccines represents the best science the world has to offer.”

For the short term, Barouch says the spike protein is the obvious choice for a vaccine. It’s on the surface of the coronavirus, and antibodies that can neutralize the protein also cripple the virus’ ability to attack cells. At the moment, Barouch says the research suggests a vaccine targeting the spike protein will likely work. The presence of antibodies is often used to help estimate the effectiveness of a vaccine and measure an immune response. Still, he adds, nothing is certain until the clinical trials are complete.

“We won’t know until we see the results. If the phase 3 studies are wonderfully protective, then that was clearly a pretty good decision,” he says. “If they fail, then there’ll be serious questions.”

Once the first vaccines get federal approval, it will still take months, at the very least, before scientists know whether they provide long-lasting protection. If they prove to be ineffective or only partially effective, Barouch says the world will have to wait for the next generation of vaccines, which will hopefully be better. Several companies, including De Groot’s EpiVax in Providence, are working on those vaccines now.

However, the federal government hasn’t made those vaccines a priority, says John Lewis, the CEO of Entos Pharmaceuticals in Canada and San Diego-based Aegis Life, Inc, which is working on a coronavirus vaccine. He asked Moncef Slaoui, the head of the federal government’s main vaccine development initiative, if he planned to allocate funding towards diversifying coronavirus vaccine candidates.

“I said, ‘do you have a plan if spike protein doesn’t turn out to be ideal, a backup plan to produce other vaccines?’ And he basically responded saying, ‘I don’t think we’ll need to do that,’” Lewis says. “I was disappointed when I heard that answer.”

Critics argue the government's strategy might slow down the development of the next generation of vaccines. But Berkeley’s Hellerstein says if it turns out the leading vaccines are just mediocre, they might still be able to slow down the pandemic enough for new vaccines to come to the rescue.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if the first vaccines are OK. Then we buy a little time," he says. "During that time, we should pick a great vaccine.”

This segment aired on November 9, 2020.