Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

As The FDA Reviews Moderna's Vaccine, Scientists Are Already Celebrating

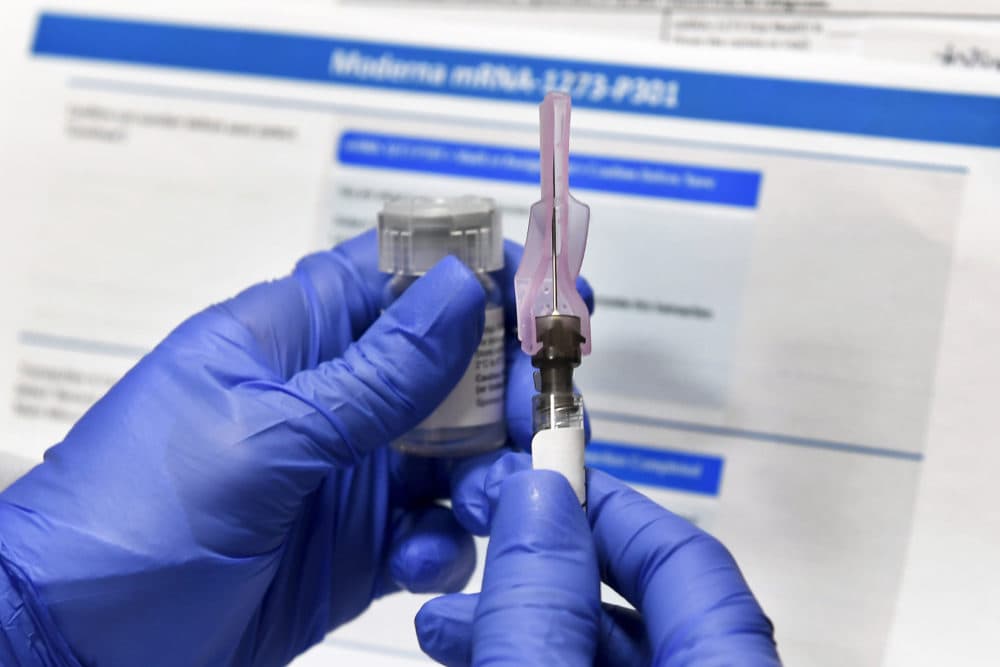

For the second time in two weeks, the FDA is on the cusp of authorizing a coronavirus vaccine. This one is from Cambridge-based Moderna. After reviewing a Food and Drug Administration evaluation of data from clinical trials released on Tuesday, health experts expect a repeat of the Pfizer vaccine’s prompt emergency authorization last week.

“If people read the 53 pages of the FDA evaluation of the Pfizer vaccine and the 54 pages of the Moderna vaccine and looked at all the data, I think they would all be very confident tomorrow to take the vaccine,” says Barry Bloom, an immunologist at Harvard University who is not on the independent FDA committee.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, given how close the two vaccines are in design and technology, the data from Moderna’s phase three clinical trial shows very similar results to Pfizer’s. After the full two dose regimen, Moderna’s vaccine has a roughly 94% efficacy rate — indicating that the vast majority of those who receive both doses should have strong protection against COVID-19.

Like Pfizer’s vaccine, uncomfortable side effects like headaches, pain or soreness at the injection site and fatigue were common. But these side effects were not serious and lasted only a day or two. Bloom says the vaccine showed “extraordinary safety.” And that means the country will likely soon have two highly effective and safe vaccines to guard against COVID.

“Terrific,” Bloom says. “The fact that we have two vaccines now is going to be a real help. It's still going to be a major logistical effort to get a large proportion of Americans vaccinated.”

Because supply of both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines is limited, front-line healthcare workers and those at the greatest risk of death from COVID are receiving the first injections. As more of the population becomes inoculated against COVID, particularly older Americans and those with conditions that increase the risk for COVID complications, it's likely that deaths will begin to decline, says Dr. Chris Gill, an immunologist at Boston University.

"I imagine the way this plays out is you vaccinate all the grandparents first and 90% of deaths are in grandparents, then we can basically reduce the death toll very quickly even though community wide transmission continues a bit longer," Gill says. "But that's OK. If we can protect that at-risk population, we've achieved a big portion of what we're trying to accomplish."

Moderna’s vaccine will be particularly convenient, Bloom says, because it only has to be stored at negative 20 degrees Celsius — a little colder than a typical home freezer. That means it doesn’t need to be transported on dry ice, as Pfizer's vaccine does, and it can be distributed at health centers, pharmacies or even post offices, Bloom says. Though, he adds, when it comes to the rest of the world, many low- or middle-income countries may still find maintaining those cold temperatures a challenge throughout the distribution process.

Advertisement

Moderna is selling its vaccine for a profit, and Bloom says he will wait for vaccine prices to come down before taking one himself.

“I’ve made a commitment not to take a vaccine that can’t be taken by people in low-income countries,” he says.

If the FDA authorizes Moderna's vaccine for emergency use, a move that may come as soon as this weekend, distribution may begin as early as next week. The speed of the development of these early coronavirus vaccines has been remarkable, says Dr. Benjamin Linas, an epidemiologist at Boston University.

“I think it’s probably the greatest achievement of human science to date. All the knowledge is like multiple Nobel prizes stacked on top of each other to get to this point. It's remarkable if you look at how long vaccines are supposed to take to develop — sometimes 10 years,” he says. “This only took five days to create, and the other 10 months was making sure it’s safe and works.”