Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

Why Some Scientists See 'Unlimited' Possibility In Technology Behind COVID-19 Vaccines

Resume

One of Moderna co-founder Derrick Rossi’s favorite things to say is that there are three keys to life on Earth.

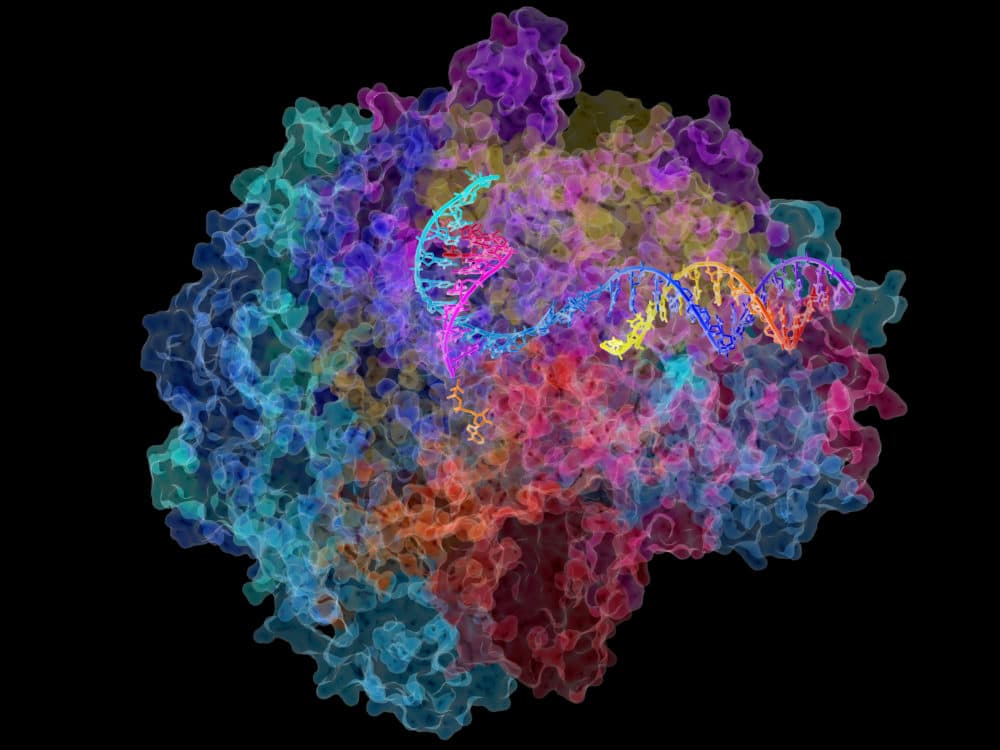

“DNA makes mRNA makes protein makes life,” he says.

The experimental technology behind Moderna and Pfizer’s coronavirus vaccines harnesses the power of one of those keys – messenger RNA, or mRNA. These vaccines are the first medical products to use mRNA in this way, but they certainly won’t be the last. A COVID-19 vaccine is just one of the near-infinite possibilities the technology offers, Rossi says.

Being able to control mRNA would allow scientists to manipulate life in astonishing new ways. It could open the door to new treatments for diseases like cystic fibrosis, cancer and HIV. Now, bolstered by the apparent success of the COVID-19 vaccine, Rossi says those other applications may soon come to fruition.

"Within 10 years time, we'll see probably dozens of mRNA therapeutics. In maybe 15 years time, we'll see maybe 50 or 60 mRNA therapeutics," he says.

Before Rossi co-founded Moderna, he was a biologist at Harvard tinkering with mRNA. DNA is often described as the building block of life, but DNA is essentially a database of information cells need to create proteins. RNA is the molecule that actually does the work of creating those proteins.

The possibilities were unlimited. You know, the RNA can encode for anything.

Timothy Springer, immunologist

For years, Rossi and other scientists tried designing strands of mRNA that would force cells to make specific proteins. But long before this technique would create the world’s highest profile vaccines, they failed.

“It totally didn’t work,” Rossi says. “So, what it looked like to the cell was the mRNA was a virus. And the cell, like a good soldier, would elicit a very robust antiviral response.”

Every time Rossi tried to insert the mRNA, the cell would either destroy the molecule or kill itself – not at all what he wanted. He felt like he'd hit a wall.

The solution came from another part of the cell – and two scientists at the University of Pennsylvania discovered it. Katalin Karikó, then a junior scientist at UPenn and now a senior vice president at BioNTech, another company that has developed a COVID-19 vaccine, was trying to do the same thing that Rossi was – and coming up empty, too. But a colleague at UPenn, Dr. Drew Weissman suggested Karikó try using modified chemical letters in her mRNA code.

“By modifying the RNA, it cloaks the RNA. It’s like giving it a fake passport,” says Timothy Springer, an immunologist at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. “And it worked brilliantly.”

“An hour later, we put the mice into this machine, and we could see this glowing spot.”

Derrick Rossi

The modified chemical letters disguised the mRNA, making it appear more or less innocent to the cell. When Rossi read about Karikó and Weissman’s work, he immediately started incorporating their technique into his own research. In one experiment, he directed cells to create proteins called Yamanaka factors that converted mature cells into stem cells. In another, he injected mice with mRNA encoded for the protein that makes fireflies light up.

“And then you know, an hour later, we put the mice into this machine, and we could see this glowing spot,” Rossi says.

The experiments were working, and now Rossi knew how to control one of the three most fundamental keys to life. He took the new data to Springer, also an accomplished entrepreneur, and asked him to help start a company based on the new technology.

Springer jumped onboard, becoming the company’s first investor. They called it Moderna – short for modified and RNA. Both still own stock in the company.

“The possibilities were unlimited,” Springer says. “You know, the RNA can encode for anything. They could be encoding secreted protein or an enzyme in the cell or a vaccine unit, you know, to protect against SARS-CoV-2.”

Over the last decade, Moderna and other companies like BioNTech have been studying modified mRNA technology as a way to develop treatments for a wide variety of diseases including heart failure and chikungunya virus. Other researchers have found ways to use modified mRNA to make advances in anti-aging research.

“The technology provides a nimble platform that you can switch things up quickly.”

Dr. Cathy Wu, Dana Farber Cancer Institute

And modified mRNA is particularly suited to creating vaccines, Springer says. That’s because while those modified chemical letters allow the molecule to sneak past cellular defenses, the compound still looks somewhat suspicious.

“It doesn’t completely sneak by. There’s a little bit of interest. Maybe the eyebrows of the immune system perk up,” Springer says.

The mRNA in a vaccine carries the code for a pathogen protein – like the spike protein from the coronavirus. When the cell begins executing the code from the vaccine and manufacturing that protein, the already wary immune system flares into action and produces a particularly strong immune response. Springer says that might be one reason why the coronavirus vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer have been so effective so far in clinical trials.

That property, along with others, make modified mRNA an attractive option for cancer vaccines, says Dr. Cathy Wu, an oncologist at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute. These vaccines train the immune system to attack tumors, but it’s expensive and takes a long time to create vaccines. That’s a problem for cancer patients.

“If someone has advanced cancer, you can’t really wait that long,” she says. “Being able to build vaccines in a timely fashion is probably what’s going to be needed to make this actually work.”

And mRNA vaccines can be made lightning fast. All you need to do to create a new one is rewrite the genetic code in the vaccine. The COVID-19 vaccine took only days to design once researchers had the novel coronavirus's genome. This could also be an advantage if the coronavirus mutates in a way that makes the current vaccines less effective.

“The technology provides a nimble platform that you can switch things up quickly,” Wu says.

Now that the COVID-19 vaccine is being produced on a massive scale, Wu says that might also help drive down some costs for the technology, as manufacturers find more efficient ways of making the mRNA. The last step remaining for cancer vaccines is to be tested in large clinical studies.

That’s true of other applications for modified mRNA, too. Wu points out that with two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines now in use, billions of dollars are going into the new technology. Other therapeutics aren't likely to be too far behind.

This segment aired on January 11, 2021.