Hundreds Of Immigrants Who Need Long-Term Care Get Stuck In Hospitals Because Of MassHealth Limits

There's a patient in a hospital north of Worcester who shouldn't be there.

She's 75 years old and suffers from dementia. A Liberian immigrant, she should be in a skilled nursing facility. But she doesn't qualify for long-term care under the state's Medicaid program, MassHealth, because of her immigration status. To qualify for that coverage, she needs a green card.

Her name is Nora Ketter. She essentially lives at Clinton Hospital — part of the UMass Memorial Health system. She's been there for three years.

Ketter is among hundreds of immigrants who get stuck in Massachusetts hospitals in a typical year, according to industry advocates.

"She deserves better," said her sister, Georgia Dennis. "But what can I do? Sometimes I feel like I have tried everything I could."

Something Wasn't Right

In the spring of 2018, Ketter was descending into her dementia.

She had been living with her sister in Worcester for a few years. Dennis had done her best to care for her. But Ketter had started to wander.

One day she got on a train to Boston. A conductor realized she was disoriented and called police. Another time, she tried to go down the staircase of Dennis' second-floor apartment with her walker.

On a particularly bad day, Ketter was refusing to eat. She was confused and had been having gastrointestinal problems. Dennis called an ambulance to take her sister to UMass Memorial Medical Center. And deep down, she knew it would be too risky to bring her sister home again. She told the hospital she couldn't.

"It was very hard for me, knowing I was the one who brought her here," Dennis said.

UMass transferred Ketter to its small hospital in Clinton. She's been there ever since.

Advertisement

'A Health Equity Issue And A Human Rights Issue'

The Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association estimates that in a typical year, several hundred immigrants end up stuck in Massachusetts hospitals, unable to move to nursing homes or rehabilitation facilities for long-term care because of immigration-related barriers to that coverage.

Some advocates say certain MassHealth rules are especially harmful to some elderly and disabled immigrant populations; specifically, the MassHealth Family Assistance plan, which Ketter is on, provides comprehensive coverage for medical services but doesn't cover the extended care so many people need later in life.

"It's absolutely a health equity issue and a human rights issue," said Andrew Cohen, senior supervising attorney at Health Law Advocates in Boston, who's worked on Ketter's case for more than three years. He calls it one of the most protracted cases he's handled involving an immigrant who doesn't qualify for long-term care.

Cohen and Dennis say UMass Memorial and its Clinton Hospital stepped up to fill the void, and the providers there love Ketter and take good care of her.

"The hospital here is absolutely doing the right thing," Cohen said. Even so, he fears Ketter has declined more quickly than she would have in a nursing home because the hospital doesn't have all the services she needs.

"They don't have the same kind of long-term supports that a skilled nursing facility would have for someone like her who has memory care issues," Cohen said. "They don't provide different kinds of programing to engage the residents. They're not set up to do that. She now is no longer able to walk."

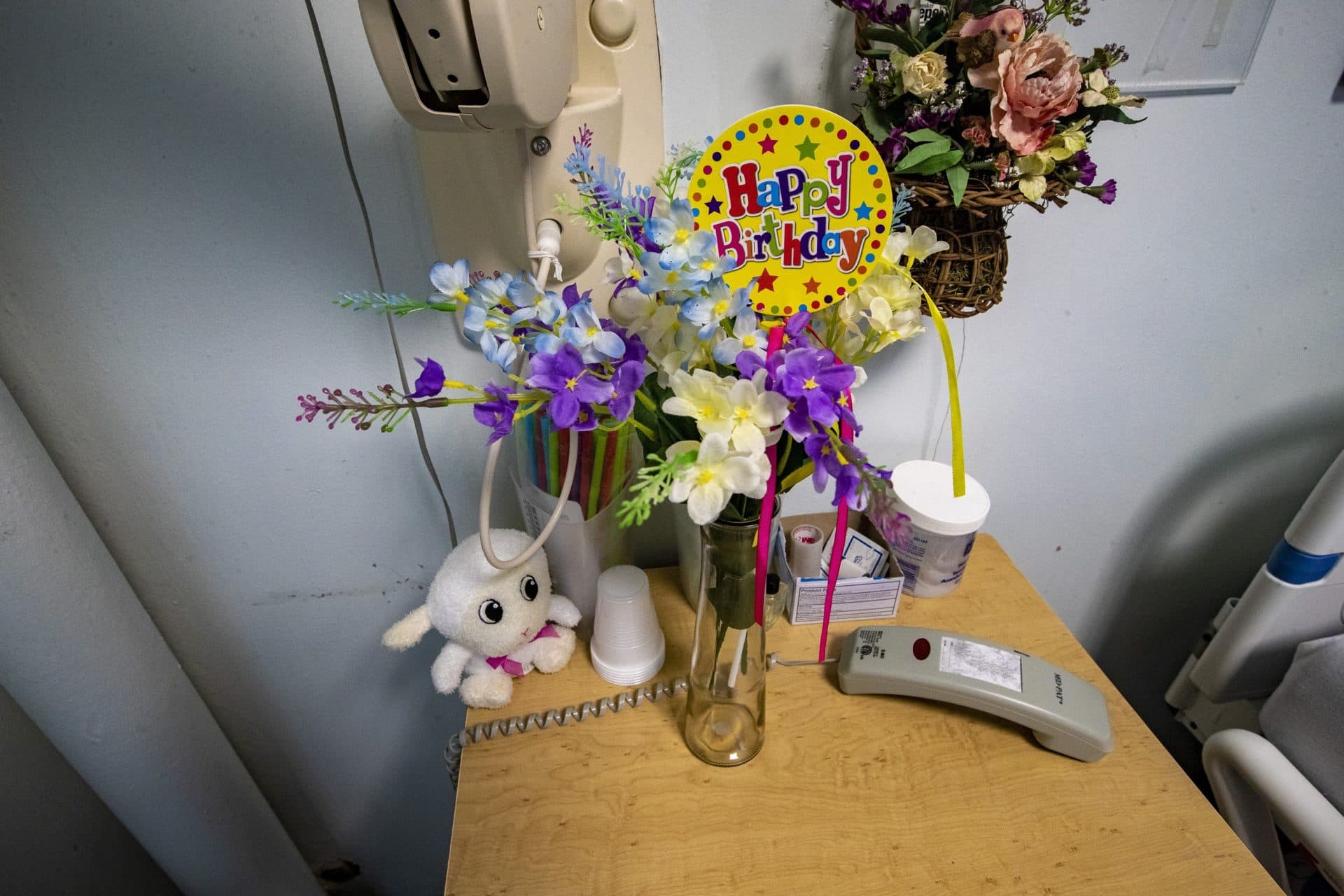

Ketter can't feed herself or get herself out of bed. She spends much of her time lying in a recliner, with a small TV playing in front of her. She responds to nurses when they interact with her, but her speech is often garbled or incoherent.

During a reporter's visits to the hospital — with the permission of Ketter's family and hospital officials — Ketter responded to a greeting, saying in a raspy voice, "Nice to meet you, too."

She laughed when a nurse called her a rock star.

Nora's Journey

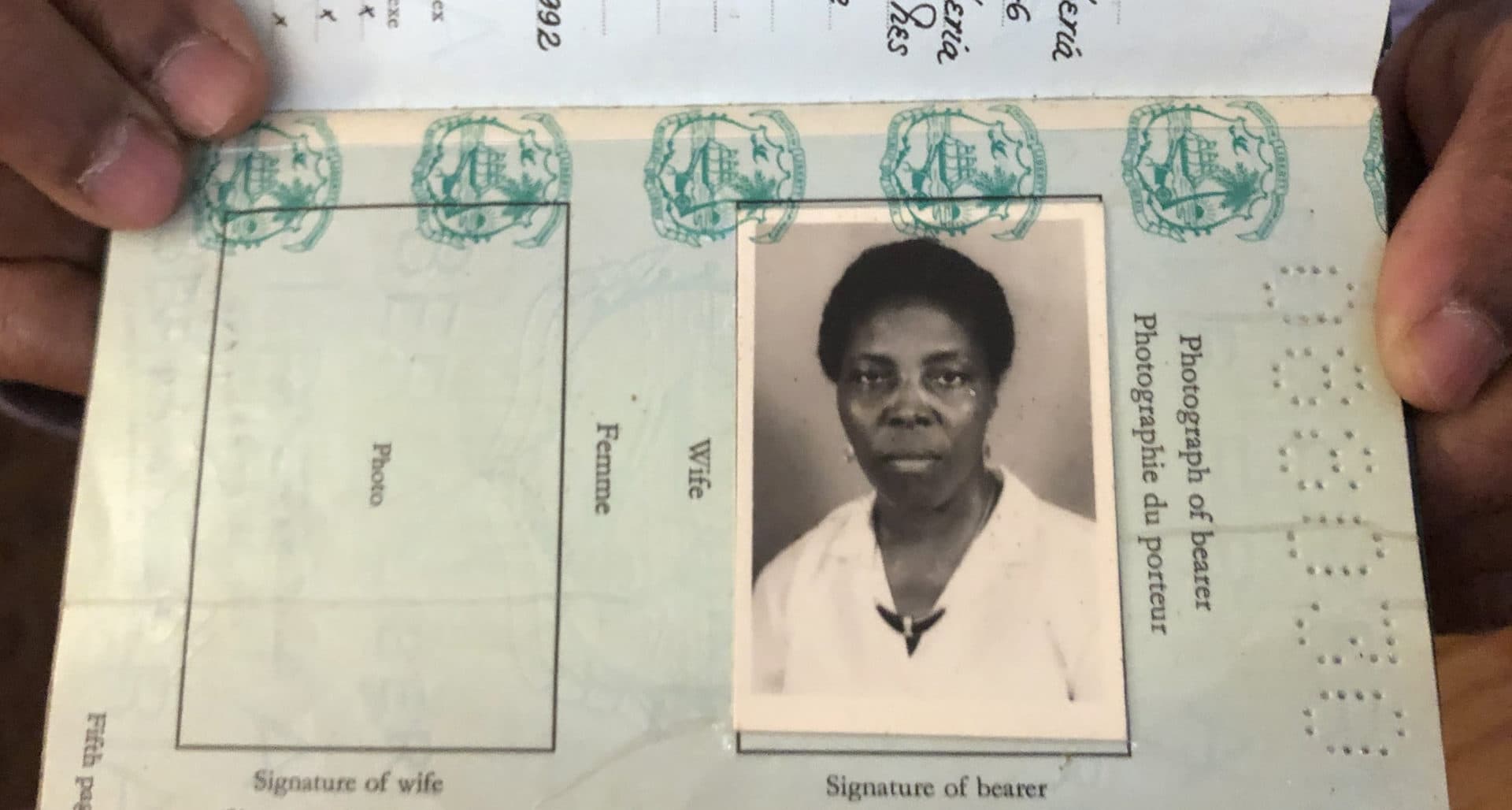

Ketter came to the U.S. on a visitor visa in 1989. A civil war was breaking out in Liberia. Her sister had already been living in the U.S. for more than a decade. A friend from Liberia was here, too.

According to her immigration attorney, Marlboro-based Eloa Celedon, Ketter feared for her safety back home because of her husband's political involvement.

So she overstayed her visa. She first lived in New Jersey, then moved to Staten Island. She worked as a nurse's aide and in-home caregiver, and sent money home to her husband and six children, according to her sister. Her family lived in a refugee camp for a long time and relied on her earnings.

One of Ketter's daughters was later killed in the conflict in Liberia. Her husband died in 2005.

As a Liberian national, Ketter has had protections from the U.S. government that allowed her to stay here, including what's known as Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure. But she waited six years to apply for asylum, instead of applying within a year as the government requires, according to Celedon. She wasn't granted asylum, and the case was eventually closed.

About six years ago, Dennis realized something was wrong with her sister cognitively. So she brought Ketter to live with her in Worcester.

Dennis later started working with Celedon to straighten out Ketter's immigration status. The two collected all of the necessary paperwork, including more than 1,200 pages of documents from immigration officials, Celedon says.

They applied for Ketter's green card two years ago, submitting letters from her UMass Memorial doctors and asking for the case to be expedited on humanitarian grounds.

"There's nothing in her case that would raise an eyebrow or would say, 'You know what, this is someone that would not merit lawful status,' " Celedon said. "All they have to do is push that button for an approval so that they can go ahead and print that green card and then have her here as a lawful permanent resident."

There is a sign of movement on Ketter's green card application. Celedon learned recently — weeks after our interview — that federal authorities will take up her case in early June.

'Immigration Status Should Not Be A Barrier'

Ketter will immediately qualify for full MassHealth coverage that includes long-term care — known as MassHealth Standard -- if she gets the green card. But there are many other immigrants who get stuck in Massachusetts hospitals and don't have that same pathway. Anyone who immigrated to the U.S. since Aug. 22, 1996 has to wait five years after obtaining lawful permanent residence to qualify for that full coverage.

When a patient cannot be discharged into long-term care, hospitals pick up the bulk of the cost for continuing to care for that person, according to the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association. Dan McHale, the association's vice president of healthcare finance and policy, says that affects the entire health care system.

"We feel strongly that immigration status should not be a barrier to receive care," McHale said. "That care ultimately is certainly financed at first by the hospital, but it's put into the system here, which is distributed and shared. That burden is shared by every single hospital in the commonwealth."

Private insurers and Massachusetts residents also pay to finance that care, through surcharges on medical bills. And the state pays a share. The pooled system is known as the Health Safety Net; it covers essential services from hospitals and community health centers for the uninsured and underinsured. It can reimburse some costs for the stays of stuck patients waiting for discharge to long-term care, according to McHale. Care not reimbursed by the safety net is often classified by hospitals as charity care or written off as bad debt.

"Massachusetts likes to think of itself as a health care innovator -- and in so many ways it is. But in our commitment as a state to universal coverage, we really have left this population behind."

Andrew Cohen

UMass Memorial didn't answer our questions about the cost of Ketter's care. According to Kaiser Family Foundation, a night in a Massachusetts nonprofit hospital costs, on average, more than $3,000.

But not all immigrant patients who lack coverage for care in a nursing home or rehabilitation facility get to wait safely in a hospital. Attorney Andrew Cohen says hospitals sometimes discharge patients to shelters, or to family members ill-equipped to care for them. In extreme cases, hospitals send patients back to their home countries.

"It's more often than not that [these discharges are] not in the patients' best interest," he said.

Cohen believes MassHealth can and should do more for elderly and disabled immigrants like Ketter, who qualify for comprehensive medical care but not long-term care. Under federal law, Medicaid plans are required to cover long-term care in a skilled nursing facility or from home health aides. Immigrants in certain categories are barred from that coverage. Still, states have leeway to offer it through their Medicaid programs. Cohen says he and other advocates have been pushing MassHealth for several years to do so.

"It would cost a lot more money to cover people in long-term care in Ms. Ketter's circumstances," Cohen said. "That said, I think from a moral standpoint, it is absolutely the right thing to do. And I think the state could find the money to do it if they really wanted to."

Other states have found a way, Cohen points out.

"New York and California, specifically, have laws that allow people in her circumstances to get this kind of care," he explained. "Massachusetts likes to think of itself as a health care innovator — and in so many ways it is. But in our commitment as a state to universal coverage, we really have left this population behind."

'I Haven't Given Up Hope'

The state's Executive Office of Health and Human Services oversees MassHealth. Department officials did not respond to WBUR's request for an interview. But a spokeswoman said MassHealth doesn't know how many of its immigrant members are stuck in hospitals because they don't qualify for long-term care; that's because MassHealth isn't billed for any covered services until after a patient's discharge, according to the state.

The agency says it insures approximately 340,000 immigrants who aren't U.S. citizens. They make up about one-sixth of MassHealth members.

Last year, the state did start covering 100 days in a long-term care facility for immigrants with complications from COVID-19 — and 100 days, even unrelated to COVID, for members of the health plan by which Ketter is covered.

According to the state spokeswoman, MassHealth would have to get additional state funding and federal approval for changes to the state Medicaid plan that would extend long-term care benefits to immigrants like Ketter.

So for now, nurses, aides and doctors at UMass Memorial in Clinton continue to care for Ketter, who has heart disease and other chronic conditions in addition to dementia. She survived pneumonia and the coronavirus in the hospital last winter, according to her sister.

Dennis prays for Ketter to be moved to a facility with more services and activities, to live out her life — however long that might be.

"I pray that she would be able to get the papers that she deserves, even if she will stay in a nursing home one day, two days, a month, however long ... so that she can be somewhere she should be ... and we can go and visit with her all the time," Dennis said.

"I'm still hopeful. I haven't given up hope, because that's all I have."

This segment aired on May 19, 2021.