Advertisement

BU Researchers Find Another Threat For Corals: Plastic

Boston University biologist Randi Rotjan has been studying coral reefs for more than a decade. A couple years ago, she started to notice tiny bits of plastic “in all of our samples from everywhere,” she says.

To understand how corals grow, she decided she was going to have to study how plastic gets into their bodies, how much is there and how it affects them.

In a new study published Wednesday in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Rotjan starts to answer those questions. She and her colleagues report that 100% of the northern star corals they collected off the coast of Rhode Island contained plastic, and when offered a choice of eating either plastic beads or brine shrimp eggs in the lab, the corals chose plastic every time.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence that plastic contamination is widespread among marine organisms. And while the long-term health effects of plastic ingestion on corals is still unclear, these results are troubling, experts say.

“Can we conclude that corals in the wild are being threatened by plastics in the same way they’re being threatened by warming temperatures and bleaching and acidification? We just don't know the answers to those questions yet,” says Kara Lavender Law, an oceanographer at the Sea Education Association in Woods Hole and an expert on ocean plastics.

But Law, who was not involved with this study, calls plastic contamination "yet another slight" against already-threatened corals. “There’s a good reason for us to be concerned," she says, "even if we don’t know exactly what’s happening.”

Rotjan notes that plastic has been found in the deep sea, in remote locations from the Arctic to Antarctica and in diverse marine organisms. Large plastic debris can weather down to “microplastics” — bits of material smaller than 5 millimeters — and work its way into food webs. “The big question in my mind is: You’ve eaten a microplastic — now what?’" she says. "This study opens the door to those ‘now what' questions.”

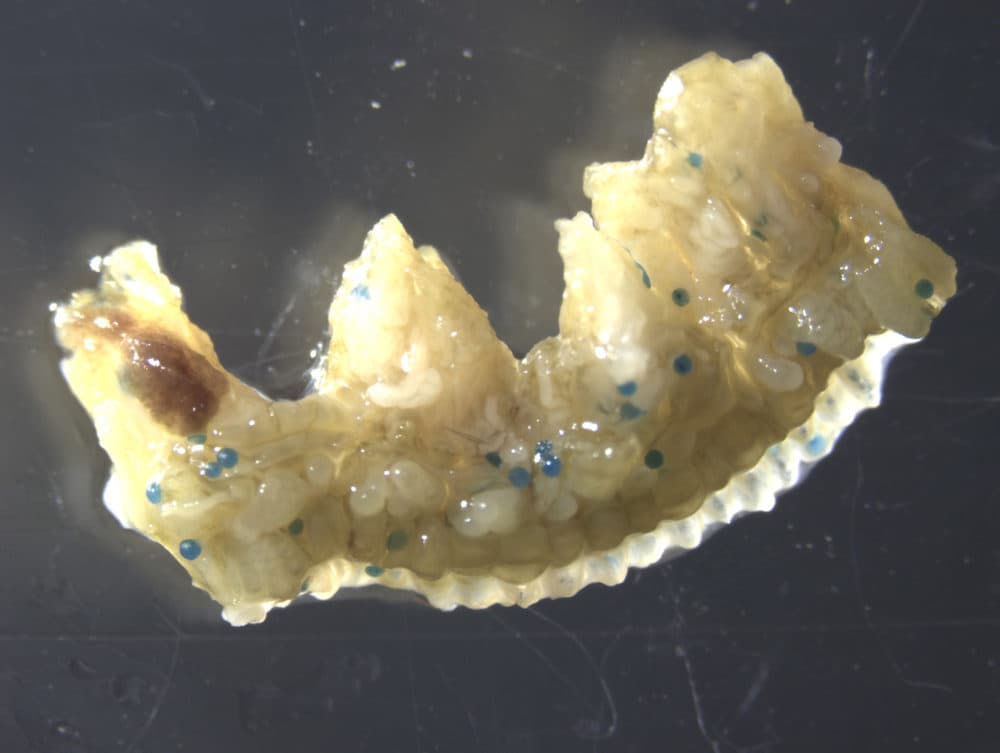

For the study, Rotjan and her team gathered samples of northern star coral, a temperate species found along the New England coast. All the wild samples they collected contained microplastics, with an average of 112 particles per polyp.

The researchers then conducted a number of experiments in the lab. They fed the corals plastic beads, then watched to see if they would eat other foods afterward, like live brine shrimp and tiny crustaceans called copepods. (They did.)

In another experiment, they offered the corals plastic beads and brine shrimp eggs at the same time, and were surprised when the corals chose to eat beads over eggs every time. (Rotjan is still unsure why.) And, the researchers coated the plastic beads with E. coli bacteria and fed them to the coral, to see if the microbes would make their way into the coral. (They did.)

Rotjan emphasizes that this research is preliminary and leaves many questions unanswered. But she suspects that the many-layered threats against corals may have a compounding effect.

“If you feed corals plastics, and the plastics have bacteria on the surface, and they’re harmless bacteria and the coral’s immune system is intact, it’s probably not going to be that big a deal in terms of microbial infection,” says Rotjan. “But if you have an infectious pathogen and a coral’s immune system is suppressed, and microplastics act as a little plastic raft where all these bacteria can hitch a ride, then suddenly maybe these plastics are not just plastics. They’re plastics with a problem attached.”

Rotjan added that the study does have a small silver lining: The wild corals were still alive even though their bodies were speckled with plastic. The fact that the corals can tolerate a certain amount of plastic may make them effective biomarkers for plastic pollution, she says, and could even suggest cleanup solutions.