Advertisement

Boston Under Water

Sam Adams In The Water: A Conversation With Historian Nancy Seasholes About Landmaking In Boston

Historian Nancy Seasholes is an expert on Boston; specifically, she’s an expert on what’s underneath Boston — the rocks, dirt and garbage that people have used for centuries to make the land on which much of the city stands. She even wrote a book about it: "Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston."

This little-known bit of Boston's history is part of what makes the city so vulnerable to flooding today. As part of our series Boston Under Water, WBUR spoke with Seasholes about what Boston's tradition of landmaking means for its future, as climate change brings more water our way.

The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

People in Boston made land for different reasons throughout the centuries. What was the first significant landmaking you found in your research?

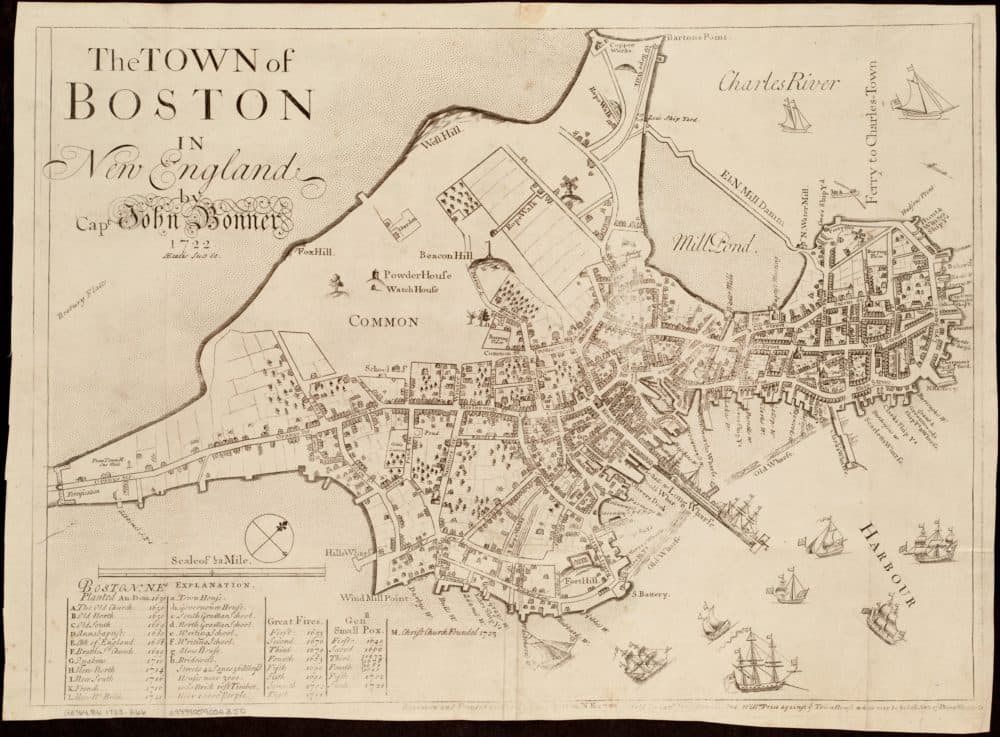

Seasholes: Well, I don't know if it's significant, but the very first was at the head of the Town Dock, which is basically on either side of what's now Faneuil Hall. The water came all the way up to what's now Congress Street.

Like, to the Sam Adams statue by Faneuil Hall?

Where the Sam Adams statue is — that was near the shoreline, but it would have been in the water. So they began filling in the sides and trying to even them off, to make it easier for ships to dock there.

How exactly do you figure this out?

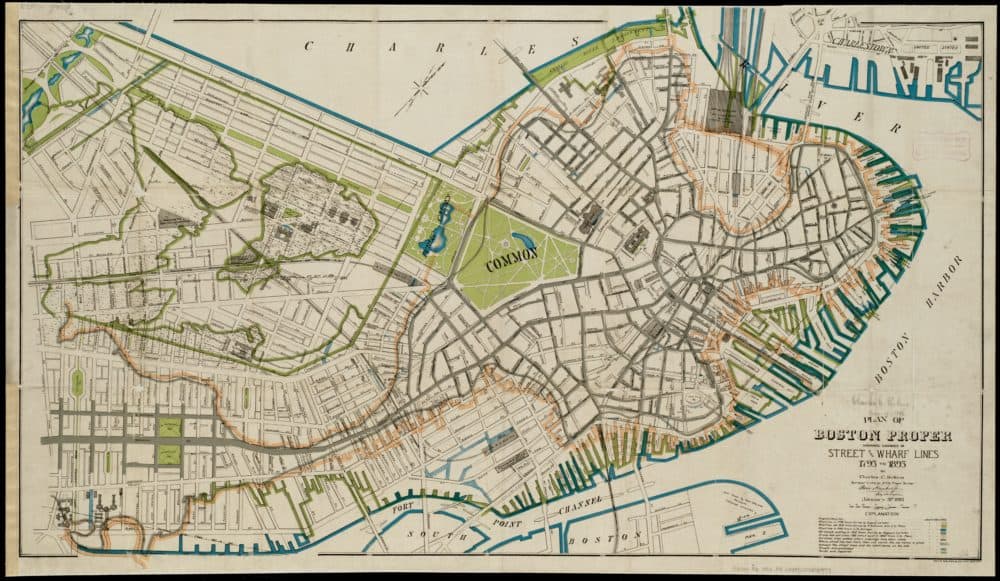

My basic sources, at first, were maps. And the key was finding a series of maps I thought were accurate, and then looking at the changes in the shoreline from map to map — that is where the land had been made, where the tidal flats had been filled in. And then I went about trying to find out why, and by whom, when and with what.

To my surprise, it was possible to find the answers to this! Especially in the 19th century a lot of the big projects were done by entities that had to file annual reports and say exactly what had been done in the past year. Finding this information was much more difficult for the 20th century. Projects like the filling of the South Boston and East Boston Flats, which had been done by the Harbor Commissioners, were taken over by the Department of Public Works, which wrote very cursory annual reports. And areas such as Commercial Point and along the Reserved Channel were filled by utility companies, whose records were hard to acquire.

Did you end up doing any actual archeological digging to figure out what the fill was made of? Or did you mostly rely on records and maps?

I mostly relied on records. The fill itself was one of the things that changed over time for various reasons.

I think when people think about “fill” they think of “landfill” and expect that all the fill was garbage. Was it?

Well originally it was. We know from excavations around Faneuil Hall and behind the Bostonian Hotel that those areas were filled with what was clearly just cartloads of trash. Like a whole lot of wine glasses where a tavern was throwing things out. But beginning in the 19th century, trash became verboten as far as fill was concerned, because people thought it was a source of disease. This was a time when people thought diseases were caused by the bad odors from rotting animal and vegetable matter, or the “miasmas,” as they called them. So you could not use trash for fill.

So what did they use?

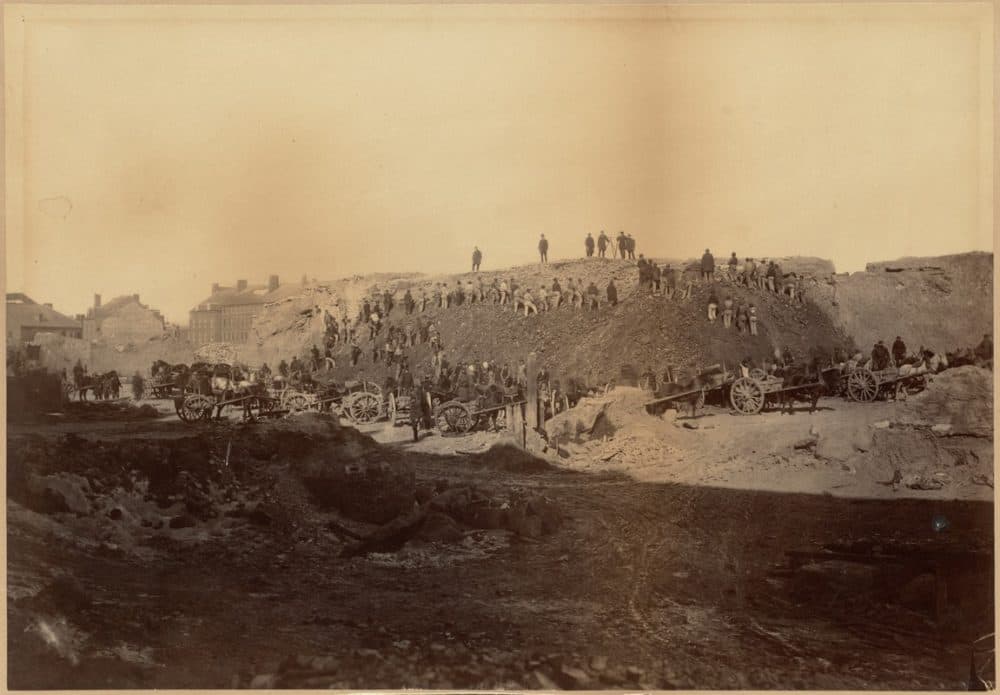

Gravel was considered one of the most desirable forms of fill because it was “clean” — it didn't have any organic matter in it. So that was why Back Bay, by law, had to be filled with gravel. It was going to be an upper-middle-class residential area, and they wanted the fill to be nice and clean. But other places were filled with mud that was dredged from tidal flats. That was not considered as desirable because it was wet. And they also used coal ashes. People burned coal for heat, and we had ash collections, like trash collections today. And then they always needed places to dump the ashes.

By the 20th century, once the germ theory of disease was accepted, trash became an acceptable form of fill. And the poster child for a trash-filled piece of Boston is Columbia Point, which was a huge trash dump for years. Everything in Columbia Point is built on 30 feet of trash, which actually has caused a lot of problems.

It’s so interesting that in the early days they had cleaner fill and better records. And then you got to the 20th century and —

Everything falls apart!

Ha! Yes. You mention in your book that Boston probably has more made land than any other city in North America. Why Boston?

Well, it turns out every large city in the United States — in fact, every city in North America that's on a coast, river or a large lake — has made land. At least until all of the regulations about wetlands came in, that seems to be the area that people found easiest to fill to create new land and increase the size of their metropolis. But although all these other large cities have some made land, it was really hard to find out how much. So that's why Boston probably has the most.

The thing that made Boston such a good site for landmaking was that it was surrounded by big areas of tidal flats. Boston was originally a little peninsula, but there were these vast areas of tidal flats around it that were fairly easy to fill.

How did they actually do it?

They would build a structure around the outer perimeter of an area to be filled, generally on the tidal flats — not in deep water, at least in Boston. During most of the 19th century, the structure was a stone seawall — and then they just dumped in fill behind it until the level of fill was above the level of high tide.

That is actually why these areas of made land in Boston are so subject to flooding now with sea level rise. It's because they didn't see any need, at the time, to fill it much above the level of the high tide. And that level is rising now.

Were you aware of that when you started doing this research?

When I began working on this, people really weren't thinking about it too much. But in my latest book, "The Atlas of Boston History," there’s a map of predicted levels of sea level rise with the original shoreline of Boston over that — so you can see that the areas most subject to flooding are the areas of made land.

What’s the most recent section of made land in Boston?

The very last part in Boston that — I think — was what was called Subaru Pier. It was down on the South Boston waterfront, near the industrial park. And it was filled in the 1980s. And that was that was where the imported cars were offloaded until the Big Dig took that space. That was where all the dirt was dumped to be taken out to Spectacle Island.

I was guessing Spectacle Island was the last one, but maybe that doesn’t count?

Well, it could! Yes, Spectacle Island then would be the last because all the dirt from the Big Dig went there. So, yes, you're right. I wasn’t thinking about the Islands, but I should! They are part of the city.

When you think about how much Boston has changed over time, one thing that’s sort of heartening, in a way, is that when people put their minds to it, they can do some pretty heavy-duty engineering feats. Do you have any thoughts on what the city should do to deal with sea-level rise?

It’s hard for me to know what actually needs to happen. Of course, all buildings need to be built on stilts. But we can’t do that. So all the mechanism of buildings — the heating systems, the elevator systems, the whole thing — all of that needs to be moved up to the roofs of buildings rather than being in the basement.

I am against a major seawall. That kind of thing has been proposed for some places, but I think Boston Harbor is too complex. I mean, I can think of a place you can put a barrier, but the water could just go around. So honestly, I don’t know.