Advertisement

As Mass. Schools Reopen, Teachers Are On The Move Again. Some See A Public-Health Risk

As the fall semester progresses, teachers and administrators are working hard to keep students, desks and classrooms separate to limit the risk that coronavirus will spread.

But that project of distancing breaks down before and after each in-person school day, with thousands of teachers commuting many miles on their way to and from work.

The range of those commutes is a reminder that communities in Massachusetts, however different, remain deeply interconnected — and that no school district is an island.

Since early August, the Baker administration has asked school districts to consider a single local metric — the average daily incidence of new cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 residents in a given community — as they shape and adjust reopening plans.

That number, simplified in a color code, should serve as a “north star” for school committees, according to education commissioner Jeff Riley.

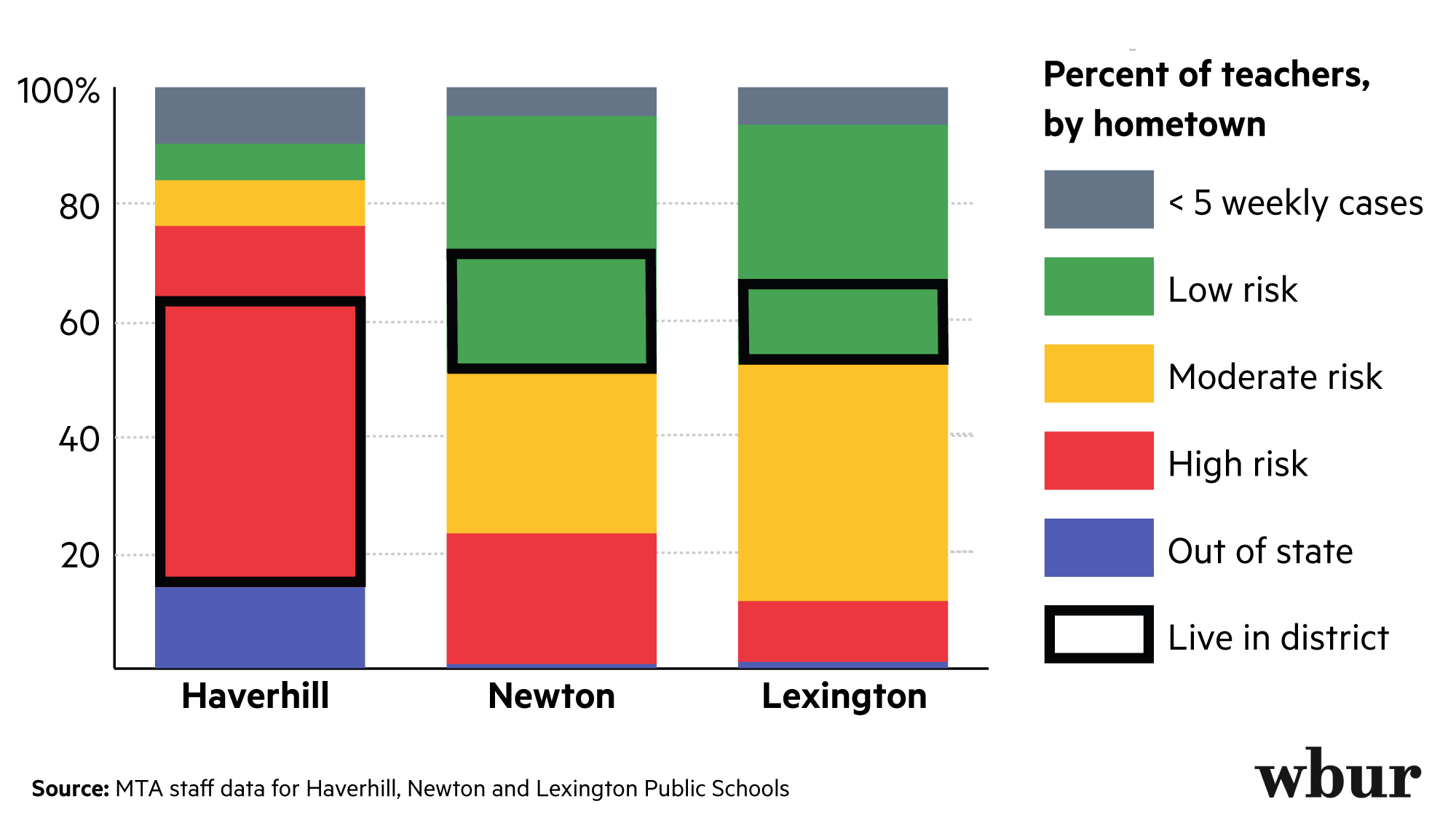

Districts coded “green” for their low COVID-19 risk should reopen in person and those with moderate risk ("yellow") should offer hybrid learning, with at least some in-person component. And in high-risk, or “red”, communities, teachers should pursue entirely remote learning — though teachers themselves should still re-enter buildings for work whenever possible, per state guidance.

Currently, the districts of Newton, Lexington and Haverhill are all pursuing a hybrid model despite widely disparate rates of COVID-19 transmission.

As a result, at least 1,600 educators are already coming into their buildings, according to staffing data shared with WBUR.

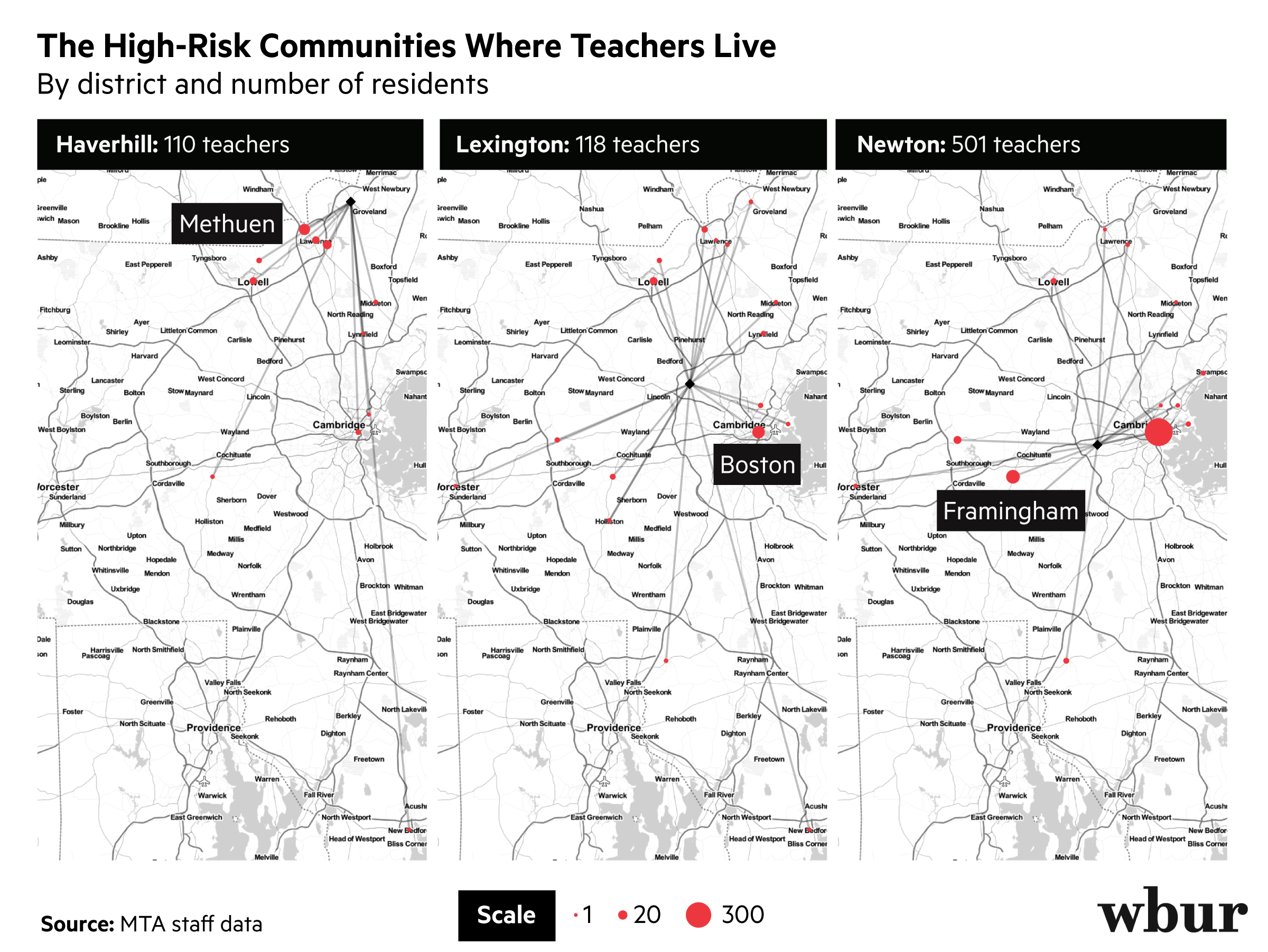

At full capacity, that number would grow to encompass almost 3,200 out-of-district educators entering schools, including 729 from communities currently labeled as at high risk of COVID-19 transmission by the state.

“It’s been very stressful,” said Christine Hickey, who lives in Medford but teaches physical education at the Tilton Lower School in Haverhill. “Going from ‘yellow’ to ‘red’ — the anxiety level’s now even more.”

State officials labeled Haverhill a "red" (or high-risk) community on Sep. 30, after it produced 129 new positive tests in the prior two weeks. That's more than nine new cases each day in the working-class city of about 64,000.

For now, Haverhill’s schools are still operating on a hybrid model. Under state guidance, a district should revert to remote schooling after it’s deemed ‘high risk’ for three weeks in a row.

Hickey — who is also the union representative for her building — said that teaching P.E. remotely this spring was “definitely challenging.”

But now that she’s back in her small, familiar gym, she has other concerns: a working husband, a son with asthma who is back in school himself — and her own diagnoses of asthma and Epstein-Barr syndrome.

Advertisement

So, like so many of the state’s essential workers, Hickey said she’s paying close, even “neurotic” attention to her movement each day, starting with her 30-mile commute in from Medford. “I drive to school” — not stopping for gas in Haverhill — “then I’ll stay in my gym — I barely move around the building,” Hickey said. At the end of the day, she said, “I get in my car and go home.”

As soon as she gets there, Hickey changes her clothes and sanitizes her shoes. “Our water bill is going through the roof,” she laughed.

In Haverhill And Beyond, A Sense of Risk

It’s not unusual for teachers to live outside the district where they teach. Only 12.8% of teachers in Lexington Public Schools live in Lexington, while 21.3% of Newton Public Schools educators live in Newton, according to staffing data.

In Haverhill, the out-of-district residents hold a much smaller majority: 49.8% of the district’s nearly 900 teachers live in the city themselves. Still, the thought of inter-community spread has worried Anthony Parolisi, president of the Haverhill Education Association (HEA), since the summer.

“The other half, they’re pretty widely spread out,” Parolisi said. 44 hail from neighboring Methuen and 14 from Lawrence — both labeled “high risk” by the state before Haverhill was. Nearly one in seven live out of state, most in neighboring communities in New Hampshire.

By comparison to Massachusetts, the Granite State has relatively low rates of COVID-19. But that leads some to fear that northeastern Massachusetts’ outbreak could bleed over the border there or in Maine.

“We’re right on the border of Plaistow, New Hampshire, and [some] of our members who live in town still do their shopping in Plaistow — tax-free shopping. It’s human nature,” Parolisi said.

As the virus has spread in and around Haverhill, Parolisi said many teachers have asked city officials — who are following state guidance — “‘Why should any of us have to come into contact with each other if we’re capable of doing this work from home?’”

Asked whether he was concerned about teachers transmitting or contracting the virus in schools, Haverhill Mayor James Fiorenti wrote, “I have not seen any evidence that supports this theory.” There are five cases in the Haverhill district so far, including three students and two members of staff.

In an interview with WBUR last week, Jeff Riley — the state’s commissioner of elementary and secondary education, who has pushed districts to reopen schools in person for months — said that as of Oct. 2, the 94 cases reported by districts were mostly “one-offs,” as opposed to "super-spreading" events.

Cause For Concern?

Throughout the summer, union officials and some community groups raised concerns about inter-district transit.

Jessica Tang, president of the Boston Teachers Union, said it informed her union’s recommendation “that only those who need to go into the school buildings do so.” Commutes and the physical availability of teachers has played a part in an ongoing battle between Newton's teachers' union and city officials.

So far this fall, there is no evidence that the virus has spread between communities explicitly because of some school districts’ physical reopening — and indeed relatively few cases appear to have arisen in schools.

Some public-health experts said that emerging research does partly support the state's push for resuming commutes — and even some in-person schooling.

“The main way [COVID-19] spreads is through clusters,” said Michael Siegel, a professor at the Boston University School of Public Health, citing research that 80% of cases originate with at most 20% of people carrying the virus.

Late this summer, Siegel harshly criticized BU and other universities that opted to open their classrooms in the fall fall. But that’s because, he said, in a pandemic, the scale and nature of exposure matter — so a single dorm room or lecture hall can become a public-health disaster area.

Commuting teachers don't present the same risk of a cluster, since they don't tend to move from one place to another together and in great numbers — only 57 teachers commute from Boston to Lexington, and just five teachers from Boston to Haverhill, for example. So even as Boston experiences a spike in new cases, the chance that a sick teacher will spread the virus to their work community remains low.

Siegel argued, as others have, that the state might have pursued a reopening model differentiated by grade, so that younger children — who are less likely to develop serious symptoms from COVID-19 or to get together in large groups outside of school — could return to class in person, while older students continued to learn remotely.

Epidemiologist Eleanor Murray, Siegel's colleague at BUSPH, agreed that commuting teachers shouldn't be the state's top priority — but she added that that doesn’t mean the current system is foolproof.

“There’s an increased risk of transmission” whenever people enter or leave a contained social context, Murray said, whether that be a classroom or a city.

So while even a large cohort of workers — the nearly 400 teachers commuting from Boston into Newton, for example — might be entirely safe on a given day, “it’s happening district by district, around the country, week after week," Murray said. "Eventually, at some point, it has happened enough that, probabilistically, you’ll see some transmission.”

She also sought to reframe the debate.

“We should be providing support to give people what they need,” Murray said, including in-person schooling for students with disabilities or language needs. “But for other kids — whose parents just need childcare — maybe we should think about other solutions that don’t involve the same risks.”

In any event, Murray warned against an attempt to forcibly subdivide the state, arguing that it wouldn’t work and — if anything — would tend to reinforce the geography of stark inequality in Massachusetts.

(Max Larkin/WBUR) She cited a recent example of neighborhood-based restrictions imposed in Madrid, Spain — similar to those now being taken up now in New York City. Murray pointed to research that suggests that approach “often doesn’t really mesh with how people live their lives.”

In Madrid, policymakers found that “the areas of the city that had the highest case count were the places where the essential workers were most likely to live” — principally denser, lower-income precincts.

But those workers’ essential responsibilities carried them outside the local lockdown, which rendered it ineffective, Murray said. Her lesson is that, even across broad physical and cultural distances, “our communities are connected in really important ways.”

As such, the goal would be a policy that allows for safe, in-person contact wherever it is truly needed, and that keeps — and supports — people at a distance everywhere else.

This segment aired on October 7, 2020.