Advertisement

The faker: Deepfakes, lies, and cheerleading

Resume

Sixteen-year-old M.H. was excited for another year on her cheerleading squad in suburban Pennsylvania. But the year was cut short when an anonymous number texted a video of her vaping to her parents and the cheerleading coaches. Vaping was against the squad’s code of conduct. The thing was, when local police investigated, they determined that the video wasn’t of M.H. According to officials, it was a deepfake sent by another cheerleader’s mother.

Show notes

- A Bucks County woman created 'deepfake' videos to harass rivals on her daughter's cheerleading squad (Philadelphia Inquirer)

- A Bucks cheerleading mom was found guilty of harassing her daughter’s rivals (Philadelphia Inquirer)

- The Truth About The Viral Cheer Mom Deep Fake Scandal (Cosmopolitan)

- Deep Fakes: A Looming Challenge for Privacy, Democracy, and National Security (Robert Chesney and Danielle Keats Citron)

- Deepfakes Web

- Resemble AI

Support the show:

We love making Endless Thread, and we want to be able to keep making it far into the future. If you want that too, we would deeply appreciate your contribution to our work in any amount. Everyone who makes a monthly donation will get access to exclusive bonus content. Click here for the donation page. Thank you!

Full Transcript:

This content was originally created for audio. The transcript has been edited from our original script for clarity. Heads up that some elements (i.e. music, sound effects, tone) are harder to translate to text.

Vinny Vella: I would say homicides are a large portion of what I cover. I also cover police misconduct cases, violent attacks, things like that.

Dean Russell: So, this case is a little bit of an oddball for you.

Vinny: Yeah, certainly is unique. I can't say that I've covered a deepfake case in my entire journalism career before this. So it was the first time for me, definitely.

Ben Brock Johnson: Amory, you recognize one of these voices, right?

Amory Sivertson: I do, I do. Dean Russell. Our producer.

Ben: Extraordinaire. A couple of months ago, Dean was talking with another journalist.

Vinny: I am Vinny Vella, and I am a staff writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer. And I cover courts and crime in the suburbs around Philadelphia.

Ben: Vinny Vella, which is a great name. Vinny Vella told Dean a story about something that happened in one of those suburbs, in Bucks County. Dean told me, and neither of us could forget this ever since then.

Vinny: It was an email that I got from somebody in the community.

Ben: Back in March of 2021, Vinny got a tip with an odd allegation.

Vinny: On the surface, I thought that was bizarre. I mean, I couldn't believe this was true. But then, when I searched for this woman's name, it turned out that she had been arrested, criminal charges had been filed, and the documents seemed to bore out what this person said. The prosecutors were asserting that this is what happened.

Ben: What happened involved a group of cheerleaders.

Vinny: Several parents of teenage girls on a cheerleading team in Bucks County had received anonymous text messages from an unknown number.

Ben: Actually, a couple of unknown numbers. Some had been texting parents. Some were texting the cheerleaders directly, including one girl identified at first in police reports as M.H.

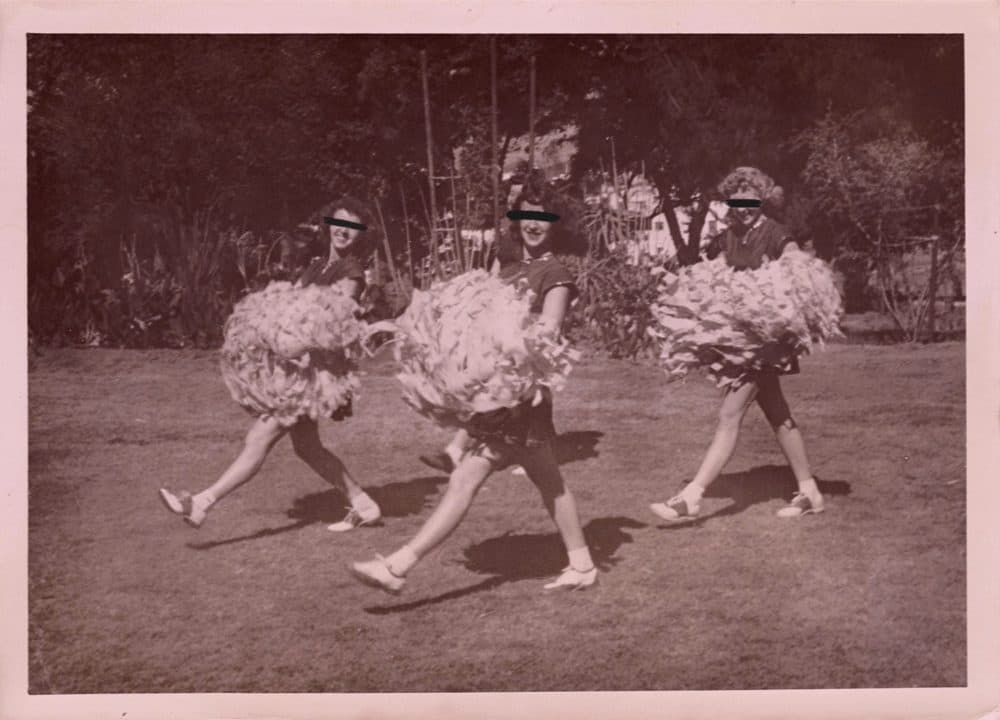

M.H. was 16 at the time. High schooler. Instagrammer. Tik Toker. She also loves cheerleading and was psyched to be on a local cheer squad called the Victory Vipers.

[Announcer: Let’s show some love for this level-two youth squad. It’s Victory Vipersssss!]

Ben: So, I think I know the answer to this, Amory, but were you ever a cheerleader?

Amory: I dabbled in school spirit. (Laughs.) I was a cheerleader until I realized you had to sit through football games, and then I was like, “Nah. Not into this.”

Ben: (Laughs.) But you’ve shaken a pom-pom or two.

Amory: Yeah, although we just call them poms.

Ben: Oh, okay, you’ve shaken a pom.

Amory: I’ve shaken a pom or two. I’ve shaken a pom and a pom.

Ben: That actually surprises me. I kind of pegged you more for a band geek. You know?

Amory: I am very versatile. I contain multitudes.

Ben: You do. You’re a renaissance woman. So, I should say, the Victory Vipers are a competitive, travel team, very different from what you or I probably remember from high school, right? Like, there’s very little cheering, but there is intense acrobatics to dance music. And the Victory Vipers, they are award-winning.

So, parents started getting these messages, which were not exactly what a cheerleading parent wants to see.

Vinny: That included photos and video clips of their daughters smoking vapes, drinking alcohol, you know, in varying states of undress.

Ben: At the same time, M.H. and two other cheerleaders said they were getting voicemails and texts that were disturbing.

Vinny: There were also messages saying, you know, there were threats saying “you should kill yourself” and other sorts of incendiary language.

Amory: So, it was the same person texting the parents and the cheerleaders?

Ben: So, at that point, it was unclear. But, on top of all of this, the parents heard from the girls’ coaches, who, it turned out, were also getting messages with these photos and videos. And this was bad news for M.H. and the other girls. Because, as Vinny Vella said, the images showed them doing things they probably shouldn’t have been doing, right?

Amory: Things that would get them kicked off the team.

Ben: Exactly. And this was going on for several months.

Amory: So, what happened?

Ben: Well, the parents were creeped out. So, they called the police.

Vinny: The detectives traced these messages to a spoofing app, an app that allows you to send messages through a randomly generated phone number. That app was later traced back to this woman, Raffaela Spone.

Ben: Raffaela Spone. She’s 51. She was using an app called Pinger, which lets people text from random numbers. The police got a search warrant for Pinger. And from there, it was pretty easy.

Amory: Who is Raffaela Spone?

Ben: Another great name, just like Vinny Vella.

Amory: That’s right.

Ben: It turned out that Raffaela Spone is a cheer mom. Her daughter was also a Victory Viper.

Amory: Ohhhh. Well, if her daughter’s also a Victory Viper, maybe her daughter was just fighting with some of the other people on the squad?

Ben: Yeah, so, it seemed this mom had it out for M.H. and the other girls, right? They were, according to TV news reports, her daughter’s rivals. Teenage nemeses, maybe. But what was surprising and even a little hard to believe was this part:

Vinny: The parents and the detectives presented these videos and photos as deepfakes. As their actual daughters' faces on, you know, someone else’s body in the traditional sense of a deepfake.

[Bucks County District Attorney Matt Weintraub: But our allegation is that Ms. Spone took existing images from existing social media from these three victims’ existing social media accounts and manipulated them or spread lies that were attached to these manipulated media.]

Ben: The investigation presented by the Bucks County D.A., Matt Weintraub, said that M.H. hadn’t vaped or drank on camera, the girls weren’t in nude photos. They were fakes. Deepfakes.

Amory: Deepfakes, deepfakes? Like, face-swapping videos?

Ben: Right. Incredibly real looking. Amory, have you seen the Tom Cruise deepfakes on Tik Tok?

Amory: I’ve heard legend of the Tom Cruise deepfakes on Tik Tok, but I’ve never actually seen them.

Ben: I mean. They’re nuts. It’s the spitting image of Tom Cruise saying things Tom Cruise would never say.

[Fake Tom Cruise: Hey, what’s up Tik Tok? Look, I do a lot of my own stunts, but I also do a lot of industrial cleanup.]

Amory: So, this is usually when you take a real recording of someone and use artificial intelligence to map another person’s face onto the original face.

Ben: Yeah, it’s that face-based technology. Apparently, Raffaela Spone has some skill with technology, or at least she had access to it.

Vinny: I don’t have the capability. Like, if you asked me to do it, I don't know how to do that. But I know that there are programs that allow these types of doctored images to be created.

Ben: And Spone, whatever she did, she didn’t hold back.

Vinny: Look, I'm not involved in cheerleading culture. I'm not involved in that level of competitive sports. I don't know how toxic these things can be, but these were real messages that were sent.

Ben: And so this is the story that I want to tell you about. How deepfakes are evolving from something extremely complicated, hard to do, and niche to something that just about anyone can do, and what that means for how we understand truth and reality.

Ben: I’m Ben Brock Johnson.

Amory: I’m Amory Sivertson. And you’re listening to Endless Thread.

Ben: We’re coming to you from WBUR, Boston’s NPR station.

Today’s episode: The Faker.

Ben: Amory, having served your time as a cheerleader and knowing the culture, at least at the time that you were pomming, does it surprise you that a parent would go after her daughter’s teammates like this?

Amory: I just— My cheer squad was not that serious. I did a little cheer here, cheer there. So, yes, this sounds whack to me. But I don’t know.

Ben: Yeah. Well, it surprised a lot of people.

[NBC anchor: It’s a troubling new take in cyberbullying. A mom in Pennsylvania is accused this morning of using so-called deepfakes.]

[Good Morning America reporter: Accused of making fake videos. Threatening her daughter’s cheerleading rivals.]

[Inside Edition reporter: Girls on the squad were victims of deepfake images that appeared to show them nude, drinking, and smoking.]

Ben: After Vinny published his story for the Philadelphia Inquirer, people flipped. The news was picked up by Good Morning America, NBC, CBS, almost immediately. Maybe because, for the often overly dramatic TV newscasters, it was this perfect combination of girls being exposed and exposing themselves and technopocalypse…

Danielle Citron: I immediately knew we were going to be talking about it.

Ben: Or maybe because experts had been warning of this moment for years.

Hany Farid: So, is this the case? Is, is this the one where we see deepfakes really penetrating into the public?

Ben: So we went to a few experts. Danielle Citron, at the University of Virginia’s LawTech Center.

Danielle: I have long been writing about intimate privacy, so the privacy around our most intimate parts of ourselves and our lives.

Ben: And Hany Farid, at the Berkeley Artificial Intelligence Lab.

Ben: Professor Farid, give me a day in the life of a guy working at the Berkeley AI Lab. Do you show up, do the my-voice-is-my-passport-please-verify thing from Sneakers, and, like, high-five a robot? What is it like?

Hany: You wish it would be that cool. Usually, I'm, like, fumbling around for my keys, trying to figure out how to get into my office.

Ben: Hany and Danielle said that to understand the significance of the cheerleading case, you have to first look at the long history that brought us to this point.

Hany: In some ways, there's really nothing new here. It's just manipulated media. And let's start by acknowledging that for as long as we've been recording images and video and audio, we've been manipulating them.

Ben: Like in the 1930s, when Joseph Stalin scrubbed political adversaries from photos after he had them killed, so it looked like they never existed.

Deepfakes, as we know, are only a few years old, though. The term comes from a place we know well: Reddit.

Amory: I did not know that’s where the term “deepfake” came from.

Ben: Yeah. In 2017, a Redditor named “deepfakes” started posting extremely convincing fake celebrity porn they made using a machine learning algorithm and publicly available videos. The subreddit r/deepfakes blossomed, and more people started doing it because the internet.

Danielle: Women are so often the canaries in the coal mine. Privacy and security issues that often affect women and people from marginalized communities are just the signal that this is going to happen in a much broader scale and be used in ways that nation states will be using them.

Ben: Danielle remembers seeing r/deepfakes — which, by the way, is now banned — and, in her mind, it opened the door to a whole cast of bad possibilities. One of which was how these things would be used against women, a.k.a. nonconsensual porn, and another was the way political actors would weaponize deepfakes for their own ends.

Like, a few weeks ago, the deepfake of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky surrendering to Russia.

[Fake Volodymyr Zelensky: (Speaking Ukrainian.)]

Ben: And Hany and Danielle say that the scariest part, to them, is what’s happening now: The ability to create deepfakes is increasingly in the hands of the masses.

Hany: Two [or] three years ago, you needed a lot of video, a lot of images of a person. So, for a performer or a politician, that was pretty easy because they have a big footprint online. But what has been happening as the technology gets better and better is you need fewer and fewer images, fewer and fewer videos so that now, if you have even a modest footprint online, you are a potential victim of somebody capturing your likeness.

Ben: And while you used to have to write your own code to make a deepfake, now, there's an app for that. Several, actually.

Estimates for deepfake videos online are between 60,000 and 200,000, mostly of women. But there are also deepfakes offline.

Hany: Now, outside of the nonconsensual porn, we are seeing examples of the use of deepfakes in fraud. So, for example, in the United Arab Emirates, just a few months ago, somebody stole [$35 million] by cloning somebody's voice and convincing somebody to transfer [$35 million] as part of a corporate deal.

Ben: Oh, I just pictured my dad getting a call from me.

Hany: From you. Yes. Because you're a podcaster. So, I've got your voice. And "you" call your dad, and "you" say, “Dad, my car just broke down. Will you Venmo me, you know, $3,000?”

Ben: Oh my god.

Amory: Okay, so the cheerleading case seems like the natural next step in deepfakery. A deepfake of women — or, girls in this case — but everyday girls, for seemingly petty reasons.

Ben: Right.

[Madi Hime (M.H.): I went in the car and started crying and was like, “That’s not me on video.” Because I thought that if I said it that no one would believe me because obviously, like, there’s proof. Like, it’s a video.]

Ben: This was M.H. on Good Morning America last year. Her real name is Madi Hime. And she made quite a few media appearances.

[Hime: I think I was just so much in shock with everything going on. Like, I couldn’t really comprehend what was going on.]

Ben: For the most part, the photos and videos in question are not yet publicly available. Except one: a video of Madi vaping. One that she told her parents was a fake. And police agreed.

Amory: Do you have the video?

Ben: I do. Let's take a look.

Amory: Huh. So you just see her face very close up, and she’s using a vape pen, it looks like. And you just see her, like, puff out the smoke, and then smile, and that’s it.

Ben: Yeah, something I didn’t think would be that scandalous. You know what I mean? Like, the teens are always vaping, ain’t they?

Amory: Yeah.

Ben: Vaping in the bathroom? Whatever.

Amory: Yeah, but something bothers me about this. Because I get that there are apps and ways to do this, but if someone asked me to make a deepfake — kind of like the reporter Vinny said — I don’t know what I would—. Where do I start?

Ben: Yeah. I’m glad you raised this, Amory, because we’re going to try. It doesn’t have to be a deep vape. But it has to be a deepfake. You know? We’re going to deepfake each other — ourselves and each other. A deepfake challenge. Are you, are you ready?

Amory: Nope. But here we go. (Laughs.)

Ben: All right. We’ll see which one of us can fool the other in a minute.

[SPONSOR BREAK]

Ben: Okay, so Amory, last weekend we decided to deepfake each other.

Amory: Mhm.

Ben: And I will say for me, it was slow going. It was slow going. It was sort of like, you know, I got in, I had to download several things to make this thing do the thing.

Amory: You were doing a visual deepfake. Is that right? A picture?

Ben: I did a visual deepfake — a moving picture.

Ben: Okay, so I've been in crazy download zone. I’ve downloaded Deepfakes Web, and I've also downloaded something called 4K Video Downloader App, which is just generic enough to cause concern. But I think I’m set up to do a deepfake here. So what I'm going to do is I'm going to upload this video of Amory that I found from, like, just post-college. She's so fresh-faced. At first, I thought I was going to switch her face with the Hamburglar’s face, but then I was like, “You know, maybe that's too stupid,” and then I was like— I don't know. I just couldn't figure out what to do, but I did land on something that I think is just perfect, which is Rebecca Black's “Friday.” Amory is a singer. Rebecca Black’s a singer. You know they go together like PB&J.

Ben: So, should we play you you as Rebecca Black, the singer of the much-maligned and yet still very catchy hit, “Friday”?

Amory: Absolutely.

[Rebecca Black: Waking up in the morning / Gotta be fresh, gotta go downstairs / Gotta have my bowl, gotta have cereal / Seein' everything, the time is goin' / Tickin' on and on, everybody's rushin' / Gotta get down to the bus stop / Gotta catch my bus, I see my frien—]

Amory: (Laughs.) That's very strange.

Ben: It's weird, right? Can you see yourself in there?

Amory: I can see myself in there, but no one would ever know that. You know, like if weren't—.

Ben: I want to say, I see it in, like, the eyelids. And maybe the mouth.

Amory: Yeah, I see the eyebrows and the— and the eyes. Very creepy. Well done.

Ben: Thanks, man. Yeah, I felt pretty good about it.

Amory: I did not have such success.

Ben: Okay. All right.

Amory: So, the good news is that I made an audio deepfake. The bad news: I couldn’t use your voice because I used this site called Resemble AI, and the free version won’t let you upload audio. So—

Ben: Oh man. You’re not spending any money, Amory? C’mon.

Amory: Not on this. So I had to record my voice.

Amory: Okay, so we’ll call this “Fake Amo.” Record my voice. Generic script for robust AI voice.

Amory: It records you reading 50 different sentences to hear your voice and then create what they call your clone.

Ben: Okay?

Amory: This is a microphone check. The data recorded on this platform will be used to generate my voice by Resemble AI. ... Float the soap on top of the bathwater. ... He was now in the last stage of a deadly fever. ... Wipe the grease off his dirty face. ... For two days, Paris has been living on salt meat. (Laughs.)

Amory: I mean, it was just nonsense. For the most part. But I recorded all that, and then it like created my clone. I could type in text that I wanted my fake voice to say. So, here's an example of that:

Fake Amory: Endless Thread is a production of WBUR in Boston. If you have an untold history, an unsolved mystery, or some other wild story from the internet that you want us to tell, hit us up: endlessthread@wbur.org.

Ben: I think they would ask us to read that one again. It's like an older, drunker version of you.

Amory: (Laughs.) I don't think it sounds anything like me.

Ben: Oh, really? I feel like I'm catching that Amory vibe. It’s very slight, but it's there. Okay. But it's not. But it's still— it's not. You could see how it could work.

Amory: I don’t know, man. I mean, we make a show about the internet, and yet our deepfakes are not good.

Ben: I refuse. I reject that. My deepfake was pretty good. So, you can just go pound sand.

Amory: Okay. But that vaping video of the cheerleader, it looks so much better.

Ben: Fair.

Amory: So, I’m skeptical.

Ben: To be clear, Raffaela Spone, the cheer mom accused of making deepfakes, says she did nothing wrong. And she definitely didn’t deepfake anyone, she says. Initially, her attorney agreed to talk to us, but then he ghosted.

We also tried to talk to the supposedly vaping cheerleader Madi Hime. But even though the Himes made plenty of media appearances last year, they never returned our messages. And there may be a reason for that.

Vinny: So, I believe it was two months after the initial charges were filed. They had this preliminary hearing.

Ben: Again, reporter Vinny Vella.

Vinny: So, they brought all of the parents of the four victims up to the stand. And at one point, one of the parents said that she recognized the photos and video as things that have been posted by her daughter on social media.

Ben: Suddenly, the deepfake claim started to break apart.

Vinny: Raffaela Spone's defense attorney made this point at the preliminary hearing, and I think it's a valid one: there was never any evidence presented of the original video — the source video, so to speak — and then the doctored one. So there was never two versions. It was always just the allegedly doctored video that was sent to the parents.

Ben: The police had the so-called deepfake, but, as we know, deepfakes use real videos as their raw material. The police didn’t have that, which was a major flaw in the prosecution.

In fact, the police detective in charge of the investigation later admitted that he based his assessment solely on his own personal research into deepfakes. He probably never consulted an expert like Hany Farid because Hany noticed glaring problems with the vaping video immediately.

Hany: There was a person vaping, and that smoke in front of the face is very hard for a deepfake to create. I mean, even when I put my hand in front of my face — to synthesize that correctly because now I have to synthesize the face and also the hand. And so, occlusions around the face can be a little tricky today.

Ben: So tricky, in fact, that it’s a crucial tell in what ended up being an epic bluff. After months of publicity about this deepfake case, everyone realized something. This deepfake wasn’t a fake at all.

Amory: What?

Hany: This has got to be a great example of the liar's dividend. Somebody got caught with their hand in the cookie jar, and it is now: “Deepfake.” Right? “It's not me.”

Amory: What’s Hany talking about?

Ben: This is a term coined by the law professor Danielle Citron and one of her colleagues. The “liar’s dividend.”

Danielle: Which is, not only will deepfakes be accepted as true. But what they would also do is enable the liar to say of real video and audio, “Oh, that's not true. You can't believe your eyes and ears anymore. It's all a fake.”

Hany: Because the average person doesn't really know how the technology works. They just see the headlines, right? "Deepfake video is here, and it's scary." And so they don't know what's possible, what's not possible. And so you get to claim it's a deepfake, even if the technology has not caught up with where that is. And that's what makes the liar’s dividend so powerful.

Ben: The more familiar we are with deepfakes, especially in a superficial sense, the easier it becomes to lie about something that’s true. And the cheerleading case is one in a long line of examples of the liar’s dividend.

Danielle: And we certainly saw President Trump do that, right? Recall that, you know, the tape of him talking about how he grabbed women by the p****** and they'd let him do it?

[Donald Trump: And when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything.

Billy Bush: Whatever you want.]

Danielle: After the audio came out, he apologized.

[Trump: I said it. I was wrong. And I apologize.]

Hany: Now, fast forward a year and a half. Deepfakes are on the scene, and he's asked the question again about Access Hollywood and what does he say? It's fake.

[Anderson Cooper: Does that mean a third person has now said that the president has expressed doubts about the authenticity?

Maggie Haberman: Yes, yes.]

Hany: Don't get me wrong, there are real risks with deepfakes around nonconsensual sexual imagery, around fraud, around election interference. But it's that ability to deny basic facts of what's going on around us that I think should worry us.

Ben: It sort of shakes the very ground that we all stand on.

Hany: Yes, because think about the, the fundamental nature of democracy is that we may disagree on how to address certain ills of society, but we have to start by agreeing on basic facts.

Amory: Wow. But I have to say, you can sort of empathize with the cheerleaders. They're teenagers. Teenagers lie.

Ben: Yeah. And vape.

Amory: And do other things because they’re young and free. But what about the other photos and videos? Were any of those fake? Any of them?

Ben: It is still possible that some of the images were manipulated, but the Bucks County D.A. dropped the deepfakes allegations entirely.

This may be a complete aside, but I should also say that the lead detective no longer works for the police department because — yes, the guy who did his own research on the deepfakes — he was recently charged with 1,700 counts of child pornography possession.

Amory: Oh my god.

So, Ben, the trajectory of this larger story about deepfakes, it looks pretty dystopian. And that may be an overreaction, like, there’s always going to be “scary new technology.” But Hany is talking about an existential threat to democracy. So, what are we supposed to do with that?

Ben: There are some things being worked on right now. Hany told me that there are some proposals to give each raw original photo something like a token, basically, something linked to the hardware that did the filming that can authenticate the raw original video.

Facebook and Google and others have talked about using AI to determine whether a video is real or fake.

Ben: But Professor Fareed, are you telling me that some combination of the device makers and Google and Facebook are the ones who are supposed to save us from this?

Hany: I feel like you are being a little cynical, but yes, let's talk about this. So, I am in by no means suggesting that Mark Zuckerberg is going to be our savior. But here’s what I would argue: The same way that safety became a feature in cars over the last three decades, I think safety is going to become a feature that we want.

Ben: In other words, our collective want for safety will nudge the marketplace and government regulations, which is ultimately how car safety came about. But that could take years if it ever happens.

Amory, there is someone I know of with a less dystopian view. So, wanna take a ride?

Amory: Let me just buckle my seat belt. Yeah. Let’s go.

Matt Groh: See, there's a lot of different kind of stuff here. So, there's some bicycles. You might have heard an opera happening. This is an interdisciplinary place. We'll take this elevator right here.

Amory: Ben and I went to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to meet this someone.

Matt: So, my name is Matt Groh. I'm a fifth-year Ph.D. student in the affective computing group at the MIT Media Lab.

Ben: A few years ago, Matt saw the very dire reporting about deepfakes, but he wasn’t buying the “news at eleven” narrative.

Matt: A lot of times, we see an anecdote. We see a single deepfake, and we say, “Oh my God, that looks so convincing.” And what you probably saw was the best deepfake that exists out there or one of the top 10, because that's the only thing that's going to go viral: the very best.

Amory: Matt told us he thought humans are actually pretty good at detecting the average deepfake. So he and his colleagues set up an experiment. They asked 15,000 people to take a test to see if they could tell fake from real.

The videos were only a few seconds long, and they featured unknown actors saying uncontroversial things. The most boring deepfakes you could imagine. Turns out Matt’s theory seems to be right.

Matt: So, when you put videos side by side — a deepfake on the left and a real video on the right or vice versa — and ask people to guess which one is which, people are quite accurate, actually. So, they can spot those manipulations. And manipulations might essentially have a kind of blurriness on the cheeks, or maybe a mustache, or they had glasses, stuff like that. Those are the kind of manipulations. And people were good at it and essentially about 80 percent accurate.

Ben: People were less accurate when looking at a single video — 72 percent. But still, solid C-minus. So naturally …

Ben: Let's look at some stuff.

Matt: Cool.

Ben: Can we look at some stuff?

Matt: Yeah, yeah.

Ben: Matt made us his test subjects, showed us one of the videos, and asked us to guess.

Actor: We're going with something that I have in mind for the future changes that I just go purchasing little by little.

Amory: On the screen was a woman in what looked like a hotel room. She was wearing all black. Black ponytail. Looking off to the right, talking about who knows what.

Amory: There's something a little off about it for me, honestly, but I couldn't tell you, so I'm going to say it's real.

Ben: Well, that was my gut reaction. It's real because the shadow on her right cheek looks legit. I'm going to say real.

Matt: So this is a video that the AI was very confident on and was correct. And a video that people, in general, were pretty bad at.

Ben: Oh s***.

Ben: Deepfake. We were wrong. So then Matt showed us something more controversial: A video of North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un sitting at a desk, giving a speech directed at the American people.

Fake Kim: Democracy is a fragile thing. More fragile than you want to believe. If the election fails—.

Amory: I'm saying fake.

Ben: Yeah, me too.

Amory: This one, we got right. Matt said whoever made it probably hired an actor.

Matt: And then they also essentially probably took just a single picture of his face and did the facial landmark movement. But did that in an artistic way, hired probably a visual effects artist. Most likely. I don't know because I wasn't the one who created this thing.

Ben: Kim Jong Un is also not exactly known for speaking English in official communications.

Amory: Okay, so generally speaking, the more you work on this stuff and the more you learn about it, the more hopeful you feel that this is a problem we collectively can solve.

Matt: Yeah, I do think this is a problem that we can address. It's going to be a problem that continues to exist.

Amory: And evolve.

Matt: And evolve, for sure. But it's also a problem that we can deal with.

Amory: Ben, it’s interesting to think about that vaping video because Matt talked about hiring actors and visual effects and green screens and even trying to match the desk Kim Jong Un uses. That’s a lot of work.

Now, moms can do anything, right? Anything at all. But it’s hard to believe that anyone would go to that length just to antagonize your daughter’s rivals.

Ben: True. She still did something, though. Last month, Raffaela Spone was tried, not for deepfaking, but for harassment using texts, photos, and videos.

In the trial, it came out that those messages, the ones saying “go kill yourself” and stuff like that, those messages were never investigated, and they were never turned over to police.

Spone was tried only because she sent real images of the girls anonymously to the coaches and the parents. She said she sent them as another parent concerned about the girls’ well-being.

After four days of trial and an hour and a half of deliberation, a jury disagreed. Raffaela Spone was convicted on three counts of misdemeanor harassment. She has yet to be sentenced, but she faces a maximum of 12 months in prison.

As for Madi Hime, she’s cheering for a new squad now and maintains a Tik Tok account posting videos regularly for her 97,000 followers.

[CREDITS]

Amory: Endless Thread is a production of WBUR in Boston.

Ben: Want early tickets to events, swag, bonus content? My cheerleading videos, Amory’s vape toks, join OUR email list! You’ll find it at wbur.org/endlessthread.

This episode was written and produced by Dean Russell. And it’s hosted by us, Ben Brock Johnson.

Amory: And Amory Sivertson. Mix and sound design by Emily Jankowski.

Ben: Editing help from Maureen McMurray. Our web producer is Megan Cattel. The rest of our team is Nora Saks, Quincy Walters, and Grace Tatter.

Amory: Endless Thread is a show about the blurred lines between digital communities and a little wiener dog crossing the street. If you’ve got an untold history, an unsolved mystery, or a wild story from the internet that you want us to tell, hit us up. Email endlessthread@wbur.org.

[Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Raffaela Spone was found guilty for "cyberbulling." She was convicted on three counts of misdemeanor harassment using text messages, photos, and videos.]