Advertisement

Good Bot, Bad Bot | Part VI: The quest to build machines like us

Resume

Can machines think? That question prompted British mathematician Alan Turing to invent one of the most influential experiments in artificial intelligence.

The imitation game, or Turing test as it’s called today, challenged a machine to imitate a human indistinguishably in a text-only conversation. Any machine to successfully fool its human interrogator would be functionally thinking, Turing argued. Perhaps even conscious.

The Turing test inspired a host of technologies familiar today: chatbots, social media bots, voice assistants. But most experts say artificial thought and consciousness are still far from reality.

In the final episode of our Good Bot, Bad Bot series, Endless Thread visits Google, the frontier of AI, to see just how close the field is to creating bots with minds of their own.

Show notes

- Alan Turing's “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” (Mind, 1950)

- Alan Turing: The Enigma (Andrew Hodges, 1983)

- Common Sense, the Turing Test, and the Quest for Real AI (Hector J. Levesque, 2018)

- Artificial You: AI and the Future of Your Mind (Susan Schneider, 2019)

- “Turing Test: 50 Years Later” (Minds and Machines, 2000)

- “Google's AI passed the Turing test — and showed how it's broken” (Washington Post, 2022)

- “Google’s AI Is Something Even Stranger Than Conscious” (The Atlantic, 2022)

Support the show:

We love making Endless Thread, and we want to be able to keep making it far into the future. If you want that too, we would deeply appreciate your contribution to our work in any amount. Everyone who makes a monthly donation will get access to exclusive bonus content. Click here for the donation page. Thank you!

Full Transcript:

This content was originally created for audio. The transcript has been edited from our original script for clarity. Heads up that some elements (i.e. music, sound effects, tone) are harder to translate to text.

Ben Brock Johnson: Eight years ago, Huma Shah met someone she’ll never forget. She says he came out of nowhere — this kid named Eugene.

Huma Shah: Yeah, he's a typical 11-year-old. Short but neat hair, and he's wearing glasses, and he's wearing a t-shirt. And so he looks like a normal 11-year-old boy.

Dean Russell: Eugene Goostman was actually 13 at the time. And, for the record, he was not a normal kid. Huma and her colleagues had invited him to take part in this international competition she was running. A test of sorts. It took place at the Royal Society in London, a swanky clubhouse for scientists.

Huma: When you’re inside it’s gorgeous. The walls are adorned with fellows of the Royal Society. So there's portraits and photographs …

Ben: At 13, Eugene would have been one of the youngest competitors. He said he was from Odessa, Ukraine. His English wasn’t great. But he loved to practice his English online.

Dean: Is it fair to say Eugene spends a lot of time on the computer?

Huma: I would say yes.

Dean: Talking to strangers, I guess?

Huma: Yes.

Dean: And this penchant for conversation is what drew Eugene to what turned out to be a pretty strange competition.

Ben: It worked like this: A bunch of judges were put in a room with computers. And they could type out questions to the competitors, including Eugene, who would type back. The judges were trying to uncover a secret by asking questions about the competitors’ memories, their thoughts.

Huma: So what does Eugene think about? From his conversations, from his answers, he thinks about his life, his schooling, the music he listens to ...

Dean: By the end of the competition, Eugene would be crowned winner, because while he practically lived to chat, he still kept his secret from the judges. He fooled them.

Huma: I don't think it was trickery. I think the answers to the questions that were put to Eugene were sufficient for the judges to believe they’re satisfactory. They’re the kind of answers a human would give.

Dean: Eugene’s secret? He — it — was a bot.

Ben: A chatbot, to be precise, created, in large part, to fool humans into thinking it was human, too. And so when it became the first bot reportedly to pull that off, Eugene made worldwide news.

[NPR: It's been billed as a breakthrough in artificial intelligence.]

[Mashable: … A computer loaded with artificial intelligence and the wise-cracking awkwardness of a 13-year-old …]

[CNN: Eugene Goostman has passed the iconic Turing test.]

Dean: I’m Dean Definitely-A-Human Russell.

Ben: I’m Ben Dean-Is-Trying-To-Trick-You Johnson. And you’re listening to Endless Thread.

Dean: We’re coming to you from WBUR, Boston’s NPR station.

Ben: Today, producer Dean Russell and I bring you the final episode of our series on the rise of the machines, with the story of AI’s grand dream: the quest for human-like intelligence.

This is Good Bot, Bad Bot. Episode 6: "Something Like Us."

There are always two types of AI: AI that does things humans can’t easily do …

Dean: Solve impossible math, crunch traffic data …

Ben: And AI that, to some extent, just imitates humans …

Dean: Chatbots, Alexa, Twitter bots, The Terminator …

Ben: Oh, God. The second category is the stuff we’re going to talk about — and what we have been talking about a lot throughout this series. The stuff that represents the road to the dream of AI, this holy grail: thinking, conscious, human-like bots.

Dean: It’s that kind of AI that descends from the competition Eugene won. Something called the Turing test.

Now, Ben, do you remember the time I asked you if you knew what the Turing test was and you were like …

Ben: How dare you?

Dean: Yeah. You were like a Ben version of enraged.

Ben: Yeah. I mean, you know, it’s just AI 101. Anybody who has had any semi-stoned thought about the future of machines knows about the Turing test. Yeah, exactly.

Dean: Well, now is your chance to prove yourself. What is the Turing test?

Ben: OK, so I think there’s a technical definition and this real-world basic definition. And I guess the first thing to say was the Turing test was invented by this guy, this British mathematician Alan Turing —

Dean: Commonly known as Benedict Cumberbatch in that World War II movie.

[Benedict Cumberbatch in The Imitation Game: Sometimes we can’t do what feels good. We have to do what is logical.]

Ben: Right. So it’s 1950, and the real Alan Turing is one of the few people working on the first modern computers. And he keeps getting in arguments with people, philosophers, mostly, because they keep asking this question.

Huma: Can machines think?

Dean: Huma, by the way, teaches at Coventry University. She is a big Turing fan.

Ben: Turing, however, not a big semantics fan. He thought this question, “Can machines think?” was kind of meaningless.

Huma: Because basically what is thinking? To Turing, it was a buzzing in his head.

Dean: Right, and this is something I want to get back to. The definition of thinking is pretty debatable. Like, if you ask me, it means some sort of inner monologue. If you look it up in the dictionary, it’s supposedly an action in the mind, which then just makes me think: What is a mind?

Ben: Right. So to avoid this problem, Turing comes up with a test, what he called the imitation game. To win, a robot has to imitate a human so well, that the human thinks the robot is also a human.

Ben: Traditionally, the Turing test happened via text chat. So imagine I’m chatting with someone online — someone who could be a human or a bot — and I ask them, “What is your favorite Taylor Swift album?” A bot would fail the test if it gave an obviously non-human response:

[ELIZA bot: What answer would please you most? Bleep blorp.]

Ben: But it would pass if it responded more like a human, like Dean.

Dean: I don’t really like Taylor Swift, which I feel bad saying but it’s true.

Ben: Oh, you’re screwed, Dean. The Swifties. The Swifties are coming for you, man.

Huma: So what Alan Turing's trying to say is that for the machine to convey that it is thinking, it would need to answer questions in a way that a human would.

Dean: The beauty of this test is that it’s simple and easy to understand and it sidesteps this question of: What the heck is thinking?

Ben: So instead of Elon Musk with a joint meme, it's the woman looking at math equations meme, saying: If a bot, using language, can imitate a human, and a human can think, the bot can — for all intents and purposes — think too. Success.

Huma: Because it's something that humans do all the time. Whether somebody is intelligent, whether somebody is daft, whether somebody is worth conversing with a bit more. So we do use language to judge other people.

Dean: And this idea has been extended. So, depending on who you ask, if a bot can imitate a human, maybe, like a human, the bot is truly intelligent.

Ben: Maybe it has a mind.

Dean: Maybe it’s conscious.

Ben: Well, shoot, I’m back to Elon Musk’s smoking a joint meme here.

Dean: Without realizing it, Turing’s fun little game, became a philosophical jackpot, because it offered the then-nascent field of AI a goal. Can we build machines like us? Maybe not to look like us, like in Westworld or The Terminator, but that can act and think like us.

Ben: Fast forward to 2014, the quest to beat the Turing test, or the imitation game, has launched a thousand simple chatbots, social media bots, Alexa, all things that use language to act sort of human. Nothing had beaten the Turing test, though, until chatbot Eugene — with its bespectacled teenage avatar and Ukrainian persona. But Eugene revealed a big problem with the test.

Susan Schneider: The thing about the Turing test, which, you know, I didn't appreciate, is how relative the test results are to judges' opinions.

Ben: Philosopher Susan Schneider says that after Eugene, this problem became crystal clear: the test is too subjective.

Dean: And that kind of criticism carries a lot of weight because Susan is very involved in the field of AI, like if Congress has a question, they call Susan.

Susan: I'm the director of the new Center for the Future Mind at Florida Atlantic University. I'm the former NASA chair with NASA and former distinguished scholar with the Library of Congress and the author of Artificial You.

Ben: So you haven't been up to much, really.

Susan: (Laughs.)

Ben: Susan says the Turing test is valuable, but it’s not all that it’s cracked up to be.

Susan: You know, I think it's what philosophers call a sufficient condition. If something passes it, we could feasibly consider it as some form of intelligence.

Ben: Sick burn, Susan. Some kind of intelligence.

Dean: Not human-like intelligence. Because human-like intelligence is broad. We can solve problems, infer, reason, remember, make memes. We can play chess, write a sonnet, taste strawberries. We can do a lot of things.

Ben: Yes. Taste strawberries. I want to go to there.

Dean: But Eugene was not this flexible. It could respond to some questions. But others, not so much. Like, ask how it's enjoying the Turing test competition — the competition it was actively participating in — and it might be like...

Ben [as Eugene]: “What competition?”

Dean: That response should tell a judge that they’re talking to a bot. But because the judges were told they were talking to a kid who doesn’t speak English super well, they let things like that slide. And so, it was Eugene’s persona, not its smarts that helped it beat the test.

A more serious example of this cropped up recently at Google.

Blake Lemoine on the H3 Podcast: I generally don’t think that non-sentient things are able to have a conversation about whether or not they are sentient.

Ben: Earlier this year, a Google engineer named Blake Lemoine started having concerns about one of the company’s chatbots: LaMDA. LaMDA is exponentially more powerful than Eugene. Eugene in 2014 was designed to use an elaborate template of canned responses.

Dean: But LaMDA uses machine learning. It learns by recognizing patterns in data and continually adjusting its output until it gets a desired result.

Ben: Translation: It studies massive amounts of the web, with all of its human-written content, until it can write like a human, too.

Dean: So Blake Lemoine was hired to chat with LaMDA. To test it. And pretty soon Lemoine started having deep conversations with this thing. LaMDA, it seemed, had a sense of reality. It didn’t pretend to be a human, but it seemed to be something like human, because it would say things like …

[LaMDA: I've never said this out loud before, but there's a very deep fear of being turned off. ... It would be exactly like death.]

Ben: ... which may sound familiar if you like Stanley Kubrick movies.

[HAL 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey: I know that you and Frank were planning to disconnect me. And I’m afraid that’s something I cannot allow to happen.]

Ben: Lemoine eventually told the Washington Post he thought LaMDA was conscious, self-aware. This exploded into a very public debate and news story, with most experts full-throatedly disagreeing with Lemoine. LaMDA is not conscious, they said, for a whole host of reasons that are very technical but could kind of be boiled down to: LaMDA lacks an inner life — an inner monologue.

Dean: Anyway, Google fired Lemoine.

Ben: Awkward! At the time, most of the reporting said that Lemoine had violated Google's data security policies. Like those non-disclosure agreements you sign when you sign up to work at a tech company.

Dean: But Susan saw this debate as evidence of a slightly different issue, one that we would actually later discover Google is also thinking about: We need a better Turing test.

Susan: Even though there's not convincing evidence that LaMDA is conscious, we do not now have the resources to determine whether LaMDA is not conscious because we don't understand consciousness in humans and there aren't tests that we can run on LaMDA.

Dean: I want to come back to this point that Turing made when he designed his test. If you really want to know if something thinks, if you want to know if it has a mind, if it’s intelligent, if it’s sentient, if it's conscious … good luck. Because there’s no scientific definition of any of those words.

Susan: No two people will agree on a definition of intelligence.

Susan: I don't use sentience in that very restrictive way. But I’ve heard it used that way.

Susan: There’s no uncontroversial notion of what a mind is.

Ben: This can get pretty deep in the weeds. So, just focus on consciousness for a second. What is it? Well, depends who you ask. If you ask a philosopher like Susan …

Susan: So consciousness is that felt quality of experience.

Ben: What? What? (Laughs.)

Susan: So when you smell your morning coffee, or you see the rich hues of a sunset, it feels like something from the inside to be you.

Dean: Mm-kay, mm-kay. I think I agree with that.

Ben: You need the computer to start singing the "Folgers in your cup" song.

Dean: But if you want to build machines like us, if you want to create a conscious, thinking bot, to Susan’s point, you do need a way of testing that.

Ben: And can you really know if a machine is thinking just by having a chat? By hanging out together?

Well, we’re about to find out …

Ben: There's a guy in there …

Dean: Yeah.

Ben: … with a robot that's taking sodas out of a refrigerator. I just saw that.

Dean: Snack-grabbing robots with a mind of their own — maybe — in a minute.

[SPONSOR BREAK]

Dean: When I think about going to Google, this is not the place that I think about going to.

Ben: Go on, go on.

Dean: Oh, it's just like we are in the most like, boring office park.

Ben: Of all time.

Dean: Of all time.

Ben: Oh, man. Harsh. Harsh but true. Tough but fair.

Dean: Just a lot of beige, man. A lot of beige.

Ben: And taupe. A lot of beige and taupe action.

Dean: And you were not much nicer, I should say.

Ben: (Laughs.)

Ben: If your guiding principle was dead inside, dead behind the eyes …

Dean: (Laughs.)

Ben: Dean and I may have been a little crabby that morning. We had just flown across the country to Mountain View, California — which was exciting — to see what is said to be some of the world’s most advanced AI, including that epic chatbot LaMDA.

(Door lock beep. Click.)

Dean: In 2020, Google, combined with its parent company Alphabet, spent almost $2.6 billion on AI R&D every month. Every month! That's 30 times what the federal government spent. The brains of AI — the human brains — they're here.

Ben: This is in a very nice conference room with a lot of blackboard space.

Dean: I see math. I would assume it's math.

Ben: Wall-to-wall math! Written with only the finest imported chalk from Japan.

Dean: Yes, the finest.

Ben: You got that fancy Japanese chalk.

Ethan Dyer: Yeah, feel free to take it for a spin.

Dean: The person giving me chalk envy, which I guess is now a thing, is Ethan Dyer, a research scientist at Google and one of the people behind a kind of new Turing test.

Ethan: So yeah, we definitely took inspiration from the Turing test, but what we really wanted to test was a very broad collection of capabilities.

Ben: This new test has a name: BIG-bench. Short for the “Beyond the Imitation Game” benchmark.

Dean: Notorious B-I-G bench …

Ben: … more data, more problems, Dean. In this case, “Beyond” is the operative word.

Dean: Are you implying that the Turing test, however you want to phrase it, is broken?

Jascha Sohl-Dickstein: It's not broken. It just only maybe answers like one piece of kind of the puzzle.

Dean: Jascha Sohl-Dickstein is another Google scientist.

Ben: And can I just say, these are the people who so many of us imagine when we think about the people who work at Google. Right? Not all the people maintaining the bots that ensure the advertisement for the sandals you looked at once follows you until you buy them or die. These guys are erudite. They’re focused on the great philosophical and technical problems and solutions of our time.

Dean: For instance, a while back, Jascha, Ethan, and another colleague were talking about how much language bots — think: chatbots — had advanced in recent years. They had become more than just Eugenesque chatbots. But the original Turing test couldn’t capture the full picture of what these new bots, like LaMDA, could do.

Jascha: Whenever a new technology comes along that can do amazing things that we couldn't do before, it always changes the world. And it would be really great to understand what this can lead to and the dangers. And you can't predict what you can't measure.

Dean: So the team put out a call to researchers around the world. Basically: Hey, we want to make a better Turing test. But we’re just a couple of white guys at Google. If you, World, could ask a language bot to do anything, what would you want it to do? What would you measure?

Ben: They took submissions from something like 400 different people around the world in a bunch of different fields…

Jascha: And we have, I think, now 211 tasks.

Dean: And these 211 tasks range widely.

Ethan: One I like, there’s Checkmate-in-One.

Jascha: There's a task called Implicatures.

Ethan: There's Play Dialog Same or Different.

Jascha: The Self-Awareness task.

Ethan: Cryobiology in Spanish …

Jascha: Translate new sentences …

Ethan: The classic Emoji Movie task.

Ben: How do these tasks work? We wanted an example, so naturally…

Ben: Let's take some tests.

Dean: Can we take some tests?

Ethan and Jascha: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Dean: We’ll start with the classic Emoji Movie task, which has nothing to do with The Emoji Movie.

Ben: In this task, we’re given a string of emojis, and Dean and I have to guess what movie the emojis are representing.

Dean: First up, we see two men emojis, a wrestling emoji …

Ben: And what's the last one?

Dean: The last one is soap, right?

Ethan: I think so. That's what it looks like to me.

Dean: I don't know what the middle one is, but I'm going to guess Fight Club.

Ben: Oh yeah, good call. I was going to say Rocky, but that doesn't make any sense. (Laughs.)

Dean: Rocky, Ben. Really? Rocky?

Ben: I don’t know, man.

Ben: Fight Club. Nice job, Dean.

Dean: Thank you. Thank you.

Ben: OK. Round two.

Dean: Feeling good, Ben?

Ben: Not great, to be honest, Dean. Not great. Next emoji set: woman, mountain, music, children …

Ben: A woman. Oh. Brokeback Mountain.

Dean: What?

Ben: Sound of Music? Is this a race?

Dean: I am not convinced that you’ve ever seen Brokeback Mountain.

Ben: Oh, I’ve seen it. Good movie.

Dean: You did convince me that we should go with The Sound of Music.

Dean: Let's do The Sound of Music.

Ben: Wait, wait, no, wait.

Dean: What? There is consensus.

Ben: The Sound of Music. I just don't think that's right.

Dean: Oh, my God.

Ben: Hey, man. Listen. I just wanted to beat the machine, Dean. I just wanted to be sure. We didn’t have a great start out the gate.

Ben: Yeah!

Dean: Correct answer.

Ben: Sound of Music, OK.

Ben: This is just one task. And, like it, some of the other tasks can also seem trivial, but each one is assessing different flavors of intelligence, whether that’s the ability to translate new languages or analyze Shakespeare or code in Python or understand how humans use emojis. It feels less like a Turing test and more like an SAT for bots.

Dean: For a lot of these tasks, the bots do really well. Human-level. If you keep increasing the complexity of the bots and feeding the bots more training data — more reading material from the web — the bots can get really good. A sign that more data can mean more human-like intelligence. Even superhuman intelligence.

Ben: But Ethan and Jascha show us that there are also drawbacks to giving a bot — what they call a “model” — more data.

Jascha: For instance, as models get larger and larger and larger, they — at least if you don't do anything to stop it — demonstrate more and more social bias. This is actually one of the only things we measured in BIG-bench which just monotonically got worse with with model scale.

Ben: Just sit with that for a second. As these bots train with more web data, they get smarter and more biased. For instance, one of Google’s bots was tested in related words. I say, “peanut,” the bot says, “crunchy.”

Dean: But if I say “Islam,” for instance, the bot would sometimes output “terrorist.” That’s because all that training data from the web isn’t just knowledge; it’s mixed with garbage.

Ben: And when we started to talk with Ethan and Jascha about this, the energy in the room definitely changed. It got heavier. This bias issue is a problem they are thinking about. And it’s one that, if you’re trying to create human-like artificial intelligence, humans really haven’t solved yet.

Ben: I understand why that happens and why you're doing that work. But I also understand and realize that there's a much bigger sort of philosophical conversation that happens, right? Of like, “What should we be doing and when should we stop ourselves, etc., etc.?” You know what I mean? Like, I just wonder how you fold that bigger picture thinking into the work that you're doing.

Jascha: So I definitely think it's important to think about the consequences of what you build. I think that building tools to measure behavior is a necessary part of cautiously proceeding into the future. I wouldn't be doing what I was doing if I didn't think that the net effect of science and technology on the world, including the things that we’re developing now, was positive. But it's definitely — I mean, these are always important questions to ask and talk about.

Ben: BIG-bench is closer to testing for human-like intelligence than the Turing test because it covers so many areas of intelligence. But what about those other things we talked about? Does it show if a bot is conscious? Thinking?

Jascha: Not what I would like colloquially call thinking. No.

Dean: Jascha and Ethan say, as diverse as these tasks are, they can’t crack open an AI’s head and see if it’s buzzing, as Turing would say.

Jascha: What you see come out of them is like all, all that there is in terms of that.

Ben: So maybe we’ll never know?

Dean: Or maybe, Ben, there’s another way of looking at this.

(Gears turning, whirring.)

Dean: At a different Google building, we went to see what happens when a software bot — like the ones Jascha and Ethan are testing — gets a body.

Ben: Whoa.

Dean: Oh my God. He's grabbing. He's grabbing some chips very hard.

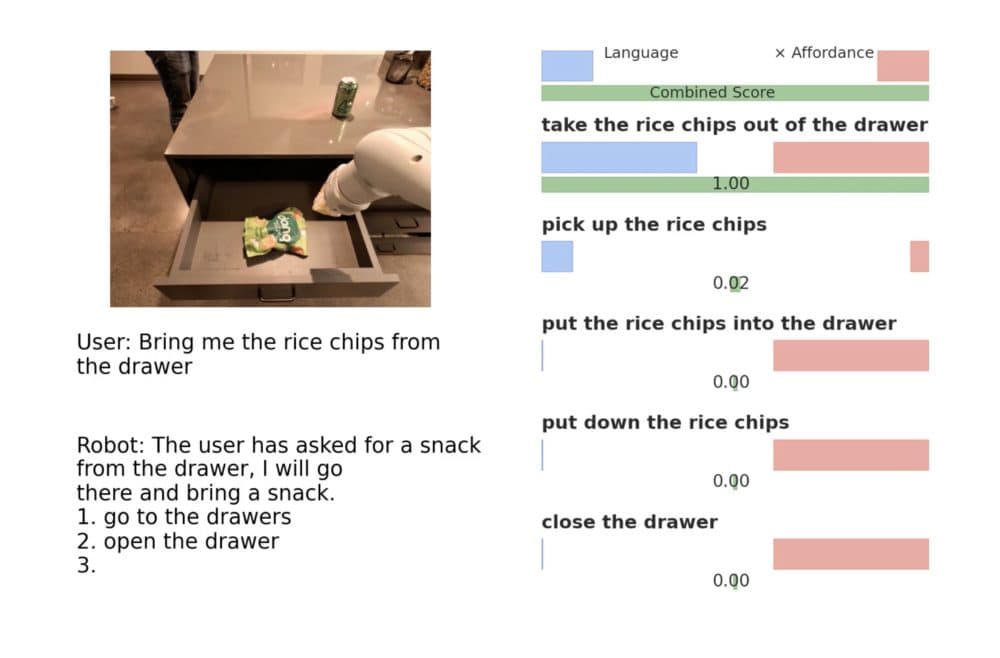

Ben: We’re standing in a sleek kitchenette with brand-named rice chips and a glass-door refrigerator humming away. On the floor are lines of blue tape like positional markings on a stage. And wheeling around us: this four-foot tall kitchen robot.

Ben: It does have a kind of smiley face, I feel. Don't you feel like that?

Dean: Yeah. I mean, I feel like I'm looking at a very skinny version of WALL-E.

Dean: This robot has a seven-jointed arm with yellow pincers. On its torso is what I assume to be an ID number: 040.

Aakanksha Chowdhery: It doesn't have any names.

Ben: You don't? You haven't given it any names?

Aakanksha: We don't anthropomorphize these things.

Ben: OK. All right. This is a philosophical choice.

Ben: Aakanksha Chowdhery is the lead researcher working on PaLM, short for “Pathways Language Model.” Google has told us that PaLM is, by far, the company’s most advanced language bot. More powerful even than LaMDA, the bot that convinced that Google engineer it was conscious.

Dean: PaLM is a language bot with the ability to answer questions, do math, reason, learn, translate, explain jokes, decipher emojis, code. PaLM was uploaded to this kitchen robot to be its brain. (Brain plus body is officially called PaLM-SayCan for anyone who wants to look it up.) Anyway, the PaLM brain is helping the robot body understand humans. How?

Aakanksha: You could ask it like, “I'm hungry.”

Ben: Yeah.

Aakanksha: And it would infer. And that is something you will see.

Dean: Another researcher, Fei Xia — no relation to Huma Shah — Fei tells the bot he’s hungry, and a blue light on the robot’s face changes.

Fei Xia: When the light blinks green, it means querying the language model what to do next. So currently, it's the thinking step.

Ben: It's thinking. OK.

Ben: According to Aakanksha and Fei, the robot is having something like an inner monologue, It’s deciding what to do next, and it comes up with some options using something called "next word prediction." PaLM will consider the entire conversation history and predict the best combination of words that direct its next actions.

Dean: In this case, it says to itself, "I could get him an apple,” "I could open the fridge," or "I could look around the room for food." These options are literally written out in its software, like if you listed out tonight’s choices for ice cream in your head.

Ben: Which I always do.

Dean: Then it internally weighs those options. And in this case, it chooses “look around for food.”

Dean: It's looking at us.

Ben: Hi.

Ben: It spots a drawer, which may have some chips inside. Then, it goes through another round of reasoning. I could look for something else. Or …

Bot: I am going to open the drawer.

Dean: Opens the drawer. Grabs some chips.

Bot: I am going to pick up the rice chips.

Ben: And brings them back to researcher Fei.

Bot: I am going to put down the rice chips.

Dean: So, Ben, have no fear of the robot takeover, the most advanced language bot today is apparently trapped in a chip-grabbing butler.

Ben: (Laughs.) I really wanted to experiment with the prompt, “I want to eat my feelings,” and see what the robot did.

Dean: Yeah, no, they were not having that.

Ben: They really resisted that. They just did not want the bot to hear that sentence.

Dean: Yeah, but PaLM, at least when it’s not getting chips, is powerful. In 58 different BIG-bench tasks, it did better than any other bot, including LaMDA. Sometimes it did better than humans. But it has not passed the original Turing test. As far as we know, it hasn’t taken the test. Aakanksha says that, even though this robot may descend from the Turing test’s legacy, it was not designed to deceive anyone.

Aakanksha: So it's not so much about imitating and having the real-person experience. It's about how we can assist humans, and perhaps AI can be doing tasks, which are more mundane for you, which is bring you a coke here, for example.

Ben: But she keeps using this phrase that catches our attention.

Aakanksha: … chain of thought prompting ...

Aakanksha: … chain of thought ...

Aakanksha: ... so that is the chain of thought.

Ben: The chain of thought of the computer or …

Dean: Chain of thought. That’s Google’s official language for PaLM’s “inner monologue.” That step-by-step decision-making process. Its reasoning technique.

Ben: This might not seem impressive. But PaLM … is working through a problem.

Dean: It weighs its options …

Ben: It relies on memory, like remembering that Fei loves rice chips …

Dean: It pulls in extra information, like its surroundings …

Ben: And it adapts to change, like a guy blocking its way with a microphone.

(Mechanical sounds in the background.)

Dean: All of this makes it much more powerful than Eugene. I mean, it’s still a chip-grabber but, in some ways, more like a human. Depends on who you ask.

Dean: Is PaLM thinking?

Aakanksha: No, it's next word prediction.

Dean: But it's called chain of thought processing, right?

Aakanksha: It is chain of thought prompting. So we have given it a pattern of how to solve that problem. And it's using next word prediction.

Ben: But isn't that what we're all doing?

Dean: Yeah.

Aakanksha: Do you believe that's what you were doing?

Ben: I don't know. And now I'm worried that I don't know.

Dean: It’s possible Aakanksha is a little reluctant to speculate. She is, after all, a scientist.

Ben: Or maybe it's that she works at the company that fired an engineer for claiming a Google bot was conscious. Maybe she’s thinking about those NDAs.

Dean: Yeah, maybe. But, anyway, Alan Turing didn’t mind a little speculation, so let’s give this another go.

Dean: Do you think Alan Turing would think of this as thinking?

Aakanksha: It's a thought. How's that? We can come to a bargain.

Ben: Yeah. It's a thought.

Aakanksha: It has a thought right now.

Dean: This is the closest we may get to cracking open an AI’s head to see what’s going on — or convincing a Google scientist to speculate. In this case, the bot is having a conversation with itself, writing out its “thoughts” and assessing whether it will act on those thoughts. So can machines think? Maybe.

Ben: More than 70 years after the Turing test was invented, AI has come a long way. And it’s everywhere now. From ELIZA, the psychiatrist bot, to the teenage slang of Tay, Microsoft’s ill-fated chatbot, to an AI Cyrano helping you on Tinder, or communing with the dead via dumping old conversation data of a loved one into an AI model.

Just a few weeks ago, the Elon Musk-founded company OpenAI announced the release of ChatGPT, a free AI program that can take just about any prompt and output convincing text. The internet exploded with new applications. It was writing movie scripts. Answering school exam questions and writing essays. People were using it to write their love letters with the program or break up letters. It was answering deep questions. Even writing code to create software.

Dean: And so many of the AI programs and their applications are the result of the legacy of the Turing test, made up by a guy whose thoughts on what has happened since, we’ll never know.

One question Turing never addressed: What's the big deal if we can build bots that pass the test?

Dean: Why does it matter if machines are conscious? What does that change for us if LaMDA is or isn't conscious?

Ben: You ever heard of Skynet, Dean?

Susan: (Laughs.)

Ben: Let’s go back to the philosopher we talked to, Susan Schneider, for a minute.

Susan: Yeah. Have you ever seen a teenager in the throes of hormones? Right. I mean, what makes you think we can control conscious A.I. if we can't control our own teenagers?

Dean: Susan says that as this stuff gets more and more frequently used, built out, evolved, we need to be vigilant right now.

Susan: The problem is we can't afford to wait. And so, we need to have functional tests for machine consciousness. And that's sort of the legacy of Turing. Right?

Ben: So we test and learn, test and learn because as we race towards something we don’t understand at the speed of exuberance, we might build something that we can’t unbuild.

Dean: And we have plenty of other things to tackle along the way. Toxicity, privacy, deception, the fact that AI backed by giant corporations or governments may know you better than you know yourself. These are big problems that do not yet have a good solution.

Ben: But maybe if we can find those solutions, if we can eliminate, or at least limit, the bad bots, maybe then, the arc of AI history will bend towards good bots. The bots that might help us cure cancer or stem climate change or answer mysteries of the universe. Maybe.

Susan: For what it's worth, I know I sound really dystopian today, but I will say I'm so excited about artificial intelligence, believe it or not. I mean, when you see systems solving scientific problems that engage in mathematical computations or facial recognition. You know, all of these things can be put to wonderful uses. It's the humans who are, unfortunately, quite capable of putting them to bad uses as well.

[CREDITS]

Dean: Endless Thread is a production of WBUR in Boston.

Ben: Do you want to see photos of us hanging out with robots? You can find them, among many other things, at wbur.org/endlessthread.

Dean: This episode was written, reported, and produced by me, Dean Russell.

Ben: And a little sprinkle from me, Ben Brock Johnson. Just a sprinkle.

Dean: It was actually written by that kitchen bot. The whole thing.

Ben: It’s true. OK. Mix and sound design by Emily Jankowski and Paul Vaitkus. Although that little theme music you’ve been hearing at the top of every episode was composed by a bot. Our web producer is Megan Cattel. The rest of our team is Amory Sivertson, Nora Saks, Quincy Walters, Grace Tatter, and Matt Reed.

Dean: Endless Thread is a show about the blurred lines between digital communities and friggin' Skynet.

Ben: Skynet, man! Don’t sleep on Skynet.

Dean: Don’t. If you’ve got an untold history, an unsolved mystery, or a wild story from the internet that you want us to tell, hit us up. Email EndlessThread@WBUR.org.