Advertisement

Book Excerpt: 'My Times In Black And White'

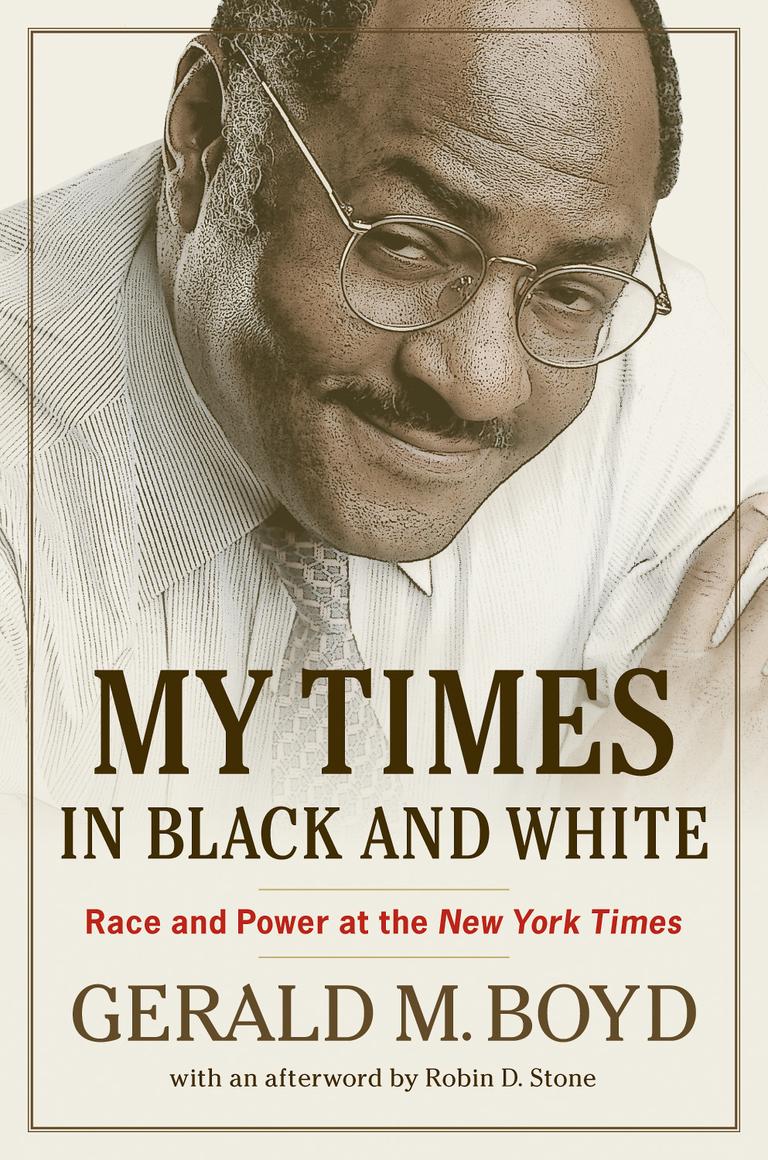

The late Gerald Boyd was the first African-American managing editor at the New York Times and was a major part of the paper’s numerous Pulitzer Prizes during his tenure. However, he was forced to resign in 2003 in the wake of the scandal of Jayson Blair, the reporter who admitted plagiarizing and fabricating news stories. In his memoir “My Times In Black And White: Race and Power at the New York Times,”published posthumously, Boyd recounts how he was accused of being too close to Blair, because both men were black. His memoir is excerpted below.

My Times In Black And White: Race and Power at the New York Times

By Gerald Boyd

From Chapter 7, "Fast Tracked": Boyd moves from the Times' Washington Bureau, where he was a White House correspondent covering the Reagan and Bush administrations, to the New York newsroom, where he assumes the role of deputy national editor.

New York scared me. There was so much about the city that I did not understand—from life in its far-flung boroughs to the overwhelming alphanumeric jumble of its massive subway system. I believed I could perform as an editor anywhere, but New York represented so much more than my job. Moving there would take me farther from my roots and away from my friends and colleagues in Washington. I would be working alongside many reporters and editors whom I had never met. And I would enter the newsroom with a strange title in a position of authority, although it was not clear what that authority meant.

New York scared me. There was so much about the city that I did not understand—from life in its far-flung boroughs to the overwhelming alphanumeric jumble of its massive subway system. I believed I could perform as an editor anywhere, but New York represented so much more than my job. Moving there would take me farther from my roots and away from my friends and colleagues in Washington. I would be working alongside many reporters and editors whom I had never met. And I would enter the newsroom with a strange title in a position of authority, although it was not clear what that authority meant.In hindsight, I was letting those old demons get the best of me. I tapped into long-held worries about status and worth and whether I was really good enough to succeed at what I assumed would be highstakes management. I did not think I could make it in New York on my own. What I needed, I surmised, was a partner whom I could trust and lean on. Who could help me put those demons to rest.

I finally asked Jackie to marry me, and she said yes. She brought companionship, added financial security, sophistication, and fine judgment. Big brother Gary was ecstatic; he was taken with Jackie’s celebrity and considered me lucky for snagging a glamorous network correspondent. Friends were supportive, though like Raines and Dowd, they had their doubts. To my litany of reasons that I thought I should marry, I added Jackie’s loyalty. Sheila, in her role as my friend and as one who had already endured my lack of commitment to the institution of marriage, shot back, “But Gerald, dogs are loyal!”

Jackie and I married July 22, 1989, in a small ceremony in Washington. Bernie was my best man and Bill Plante, a colleague from CBS, gave away Jackie, whose father had died years before. Representative William H. Gray III, the Pennsylvania Democrat who was also an ordained Baptist minister, officiated.

I moved into the house Jackie owned on Capitol Hill. Settling in came easier than I had thought. We connected with neighbors and continued our so-called power dinners with a who’s who in media and politics. Jackie was quite fond of entertaining, so I let her take the lead in making our social connections. I really did not know what I had expected from our marriage, but it seemed comforting and reassuring. As a part of such a strong team, I felt more prepared for the rigors of New York.

When the call finally came, Frankel said he was promoting Dan Lewis, then the deputy National editor, to run the Week in Review section. He wanted me to take Lewis’s place on the National desk, as number two man to Soma Golden, whom I knew from her attempt to recruit me for the Atlanta job. I had not been a national correspondent, but I certainly understood the nature of national beats from my time in Washington and on the campaign trail.

Jackie and I rented a two-bedroom apartment on the East Side, and she began searching in earnest for a place we could own. We bought a dog, an English springer spaniel that we named Sheba. Our financial outlook improved dramatically, as I participated in a bonus plan and received stock options. None of this meant immediate wealth, since the economy was stalled—there were no bonus checks and the stock options were underwater—but I celebrated my anticipated benefits. Nothing was rough about our new life together.

Work, on the other hand, was rough indeed.For the first time in my career, I came face-to-face with blatant racial tension in the workplace. When I arrived at the Times newsroom on West Forty-third Street, the environment reflected sharp divisions. Emotions were raw over the Tawana Brawley case, in which a fifteen year-old suburban New York black girl alleged that she was abducted by six white men, raped, and smeared with feces. And when a group of black and Latino youths were tried and convicted in the rape of the Central Park jogger, a white woman, the local media’s depiction of the young men as animals deepened the fault lines. These issues hung over the newsroom like polluted air.

I was no stranger to racial differences; I had faced that reality all of my life and still found a way to succeed. I did not think the newsroom would be so difficult. Clearly, I was naive. The hostility I encountered initially, which I can best describe as passive aggression, surprised me. No one ever challenged my authority outright, but I had to repeat my orders frequently and then double back to make sure they were followed.

Most of my colleagues were politically liberal and believed in racial equality. Yet many had never been in a position of having to take orders from a black person, especially one whom they did not know. In fact, few blacks were at the table when editors discussed important issues. Scanning the newsroom, I saw no black editors on the Foreign, Culture, Week in Review, Science, Sports, or Business staffs. Both National and Metro had black editors, but not in leadership positions. There were no natural avenues to discuss issues, so most racial dialogue took place through angry memos or heated conversations that a few blacks risked having. Some of those who spoke out frequently were often seen as militant—not exactly a career-enhancing label. In this highly charged atmosphere, I saw that I needed to tread carefully. I could be both a change agent and a lightning rod for racist views and assumptions.

To some colleagues, the paper’s new emphasis on diversity not only opened a door for me but also gave me an unfair edge over the competition in climbing higher. Perhaps they had a point. Still, they had to consider that the newsroom had failed previously to give blacks significant opportunities to work as editors, which was why it was in its current situation. Also, no black editor could remain in a position of authority if he or she could not deliver the goods. The Times did not operate that way. He might be demoted or sidetracked, as the Times rarely fired anyone, but he would not be in leadership for long. Finally, we blacks assuming power in the upper levels of newsrooms almost needed to have our heads examined, given the strife and isolation that we faced. I often felt that I had few people with whom to discuss my challenges, other than my wife and Paul Delaney, a former Madrid bureau chief who had been moved from deputy National editor to news administration when management determined that he was not going to rise any further. This was the same man who had once swept through St. Louis as a star reporter for the Times, the man whose future seemed limitless. Now Delaney seemed discouraged and bitter. His advice had little to do with succeeding at the Times. In fact, he warned me to watch my back.

©2010 by Robin D. Stone.