Advertisement

Reporting The Revolutionary War

ResumeIt's pretty cool to feel a piece of history in your hands. That's what we got to do when Todd Andrlik came to the Here & Now studios to talk about his book "Reporting The Revolutionary War: Before It Was History It was News" (see book excerpt below).

He brought along some of the actual newspapers he has collected from the 18th century. We got to hold them just like we do the newspapers of today.

You'd think these newspapers, some of them more than 200 years old, would be fragile or brittle, but the complete opposite is the case. Holding them feels like rubbing your t-shirt between your thumb and forefinger, because they were made from rag-linen, not wood pulp. They're incredibly durable.

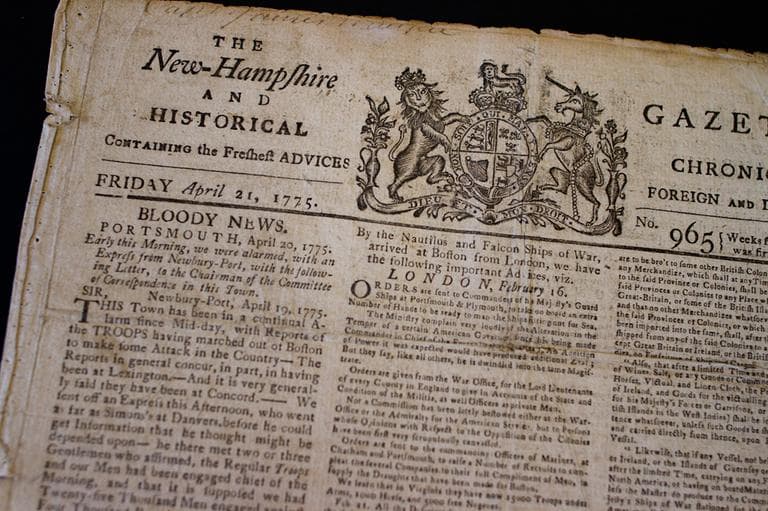

One of the newspapers Andrlik brought to the studio was dated April 21, 1775. That issue of the New Hampshire Gazette was the only newspaper in the colonies to put what we think of now as a headline over the news of the battle on Lexington Green, the first battle of the Revolutionary War. The headline reads "Bloody News." A typical newspaper in those days was only four pages long and space was a premium. So no headlines.

In the 18th century, newspapers were the social media of the day and they played a crucial role in the Revolutionary War.

"Newspapers are what fanned the flames of rebellion," Andrlik told Robin Young. "They're what sustained loyalty to the cause. They provided critical correspondence during the war and ultimately aided in the outcome."

But the papers, he said, were also where propaganda and bias were perfected, so his book includes essays by historians who give the events described in the papers some context.

What is it like to read these old newspapers in 2012, knowing the result of the Revolutionary War?

"I try to forget the outcome," Andrlik said. "But it's interesting, because you will find London newspapers that are extremely confident in what they think is the likely victory in the forthcoming months, where they think the war is about to end and that they are going to be the victors."

Interactive Graphic: Zoom in on the The New Hampshire Gazette's April 21, 1775, edition

Bonus audio: Todd Andrlik on the history of American newspapers in the 18th century

____Book Excerpt: Reporting the Revolutionary War

By: Todd Andrlik____

Introduction

There are no photographs of the American Revolution. No snapshots exist to show ordinary life or depict the struggles and suffering of the late eighteenth century. Engravings and oil paintings, made long after the war ended, portray epic battles and heroism but often fail to realistically capture the moment.

Newspapers are the closest thing we have to photos of the Revolution. They transport readers back in time, providing unmatched insight about common life and life-altering events. Despite their small size and lack of headlines, eighteenth-century newspapers pack an intense, concentrated punch and demonstrate the incredible power of the printed word. Through newspapers, we realize that history is much more than a chronological list of battles as we eavesdrop on everyday life and witness everyday realities of the American Revolution through the eyes of the British and the American colonists. The eighteenth-century newspapers presented in this book help us see that history is real life, messy, and exciting. We learn firsthand what many historians claim: without newspapers, there would have been no American Revolution.

Through vivid eyewitness accounts, battlefield letters, and breaking news compiled from hundreds of newspapers—primarily printed from 1763 to 1783 on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean—this story of the American Revolution is unlike any version that has been told. It is raw and uncut, full of intense action, drama, and suspense. From start to finish, these frontline newspapers deliver incomparable insight about America’s founding. As a collection, they provide one of the most reliable and comprehensive narratives of the Revolutionary Era, loaded with amazing characters, better-than-fiction plot twists, and the perfect climax. Before these famous and infamous events became the history and foundation of America, they were littered among the news of the day for colonial Americans. Mark Twain wrote “of the wide difference in interest between ‘news’ and ‘history’; that news is history in its first and best form, its vivid and fascinating form; and that history is the pale and tranquil reflection of it.”

Reporting the Revolutionary War brings to life precious first drafts of history and lets readers experience the charming rusticity of eighteenth-century newsprint, complete with stains, tears, imperfect ink and paper, typesetting mistakes, misspellings, and grammatical errors that were all typical of the era. Reading Revolution Era newspapers in their original form helps reproduce the same immediacy and uncertainty felt by those who first held them.

With each newspaper, readers gain valuable insight into the social, economic, political, and military histories of the American Revolution. Reading newspapers in their entirety—including advertisements, obituaries, and essays—provides more than a glimpse of all the obstacles and ideas of the period. It creates a 360-degree view of the American Revolution and the formation of the United States.

Another important history lesson to be gained from this book relates to journalism. We live in a time of instant and on-demand news. Journalists and bloggers work frantically around the clock, competing to break news stories before anyone else. Cable news channels and websites stream updated headlines nonstop across their screens. Using Twitter and Facebook, millions of citizen reporters scramble to share the latest news affecting their lives, practically in real time. Despite the debated endangerment of printed newspapers, it is difficult to imagine a time when media were more important. However, 250 years ago, newspapers were the fundamental form of mass media and were more important than in any other time in America’s history.

Just as social media helped ignite and organize the Arab Spring revolutions of the Middle East and Northern Africa, colonial newspapers fanned the flames of rebellion, provided critical intercolonial communication during the war, sustained loyalty to the Patriot cause, and aided in the outcome of the war—all of which becomes evident after reading straight from the pages of newspapers. In Reporting the Revolutionary War, readers will see that Americans maintained “Liberty or Death! Join or Die!” attitudes with blood, as well as ink, on their hands. David Ramsay, who twice served as a delegate in the Continental Congress, wrote that “in establishing American independence, the pen and the press had merit equal to that of the sword.”

Not only do eighteenth-century newspapers contain the exclusive essays, reports, and advertisements of the day, but they also include reprinted extracts from other primary sources such as private letters, journal entries, official government documents, and war-zone intelligence direct from merchants, travelers, soldiers, officers, and common colonists. They are a proverbial gold mine of information. Since the day the Revolutionary War ended, historians and authors have relied heavily on newspapers as the basis for their own analysis and interpretations of the course of the war. The endnotes of practically every history book about the Revolution are loaded with references to the up-close-and-personal perspectives found in newspapers.

Reporting the Revolutionary War brings to life eighteenth-century newspapers in a firsthand account of America’s founding, distinct from the history we receive in high school and university texts. Never before has such a significant collection of American Revolution newspapers been made available to the general public in such color and detail. Never before has access to such an archive been made so easy. And never before has this version of the American Revolution been told.

Guest:

This segment aired on December 5, 2012.