Advertisement

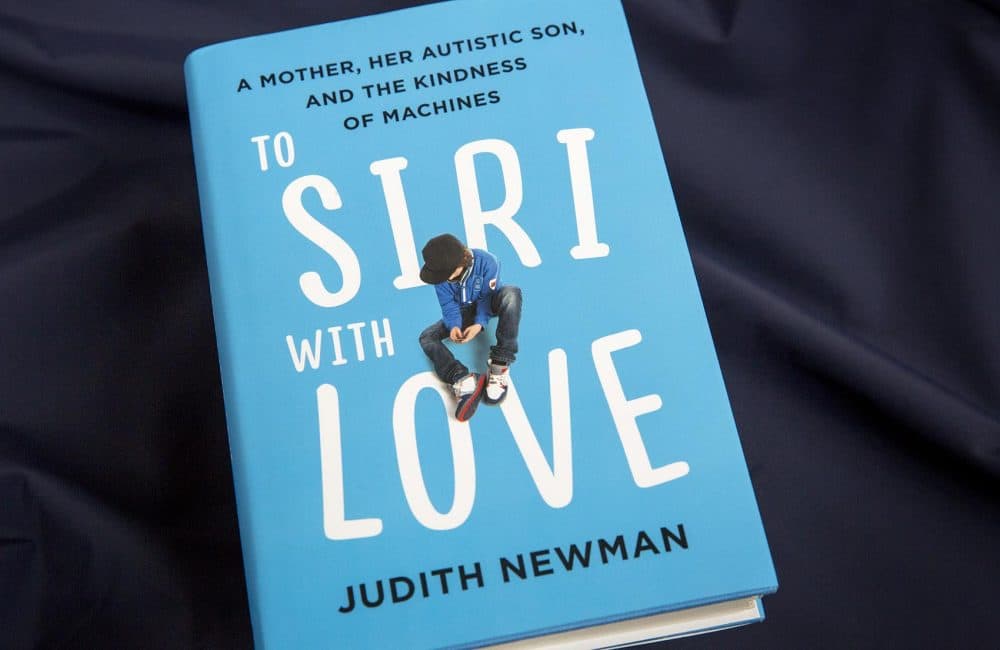

'To Siri With Love' Follows One Boy's Life With Autism — And His Unlikely Friendship

Resume

In "To Siri with Love," author Judith Newman writes about raising her twin sons — one who has autism, the other who does not.

Newman (@judithn111) joins Here & Now's Robin Young to talk about the book.

Book Excerpt: 'To Siri With Love'

By Judith Newman

My kids and I are at the supermarket.

“We need turkey and ham!”

Gus tends to speak in exclamation points. “A half pound! And . . . what, Mommy?” I’m stage-whispering directions, trying to keep the conversation focused on deli meats. Behind the counter, Otto politely slices and listens, occasionally interjecting questions. We’re on track here.

And then . . . we’re not.

“So! My daddy has been in London for ten days, and he comes back in four days, on Wednesday. He comes in to JFK Airport on American Airlines Flight 100, at Terminal Eight,” Gus says, warming to the subject. “What? Yes, Mom says thin slices. Also, coleslaw! Daddy will take the A train from Howard Beach to West 4th and then change to the B or D to Broadway–Lafayette. He’ll arrive at 77 Bleecker in the morning and then he and Mommy will do sex . . .”

Suddenly Otto is interested. “What?”

“You know, my daddy? The one who is old and has bad knees? He arrives at Terminal Eight at Kennedy Airport. But first he has to leave from London at King’s Cross, which goes to Heathrow, and the plane from Heathrow leaves out of—”

“No, Gus, the other part,” says Otto, smiling. “What does Daddy do when he gets home?”

Gus presses on with his explanation, ignoring the little detail his twin brother, Henry, whispered in his ear. Henry stands off to the side, smirking, while Gus continues with what really interests him: the stops on the A line from Howard Beach. I see the slightly alarmed looks on the faces of the people waiting in line. Is it the content of Gus’s chatter or the fact that he is hopping up and down while he delivers it? When he’s happy and excited, which is much of the time, he hops. I’m so used to it I barely notice. But in that moment I see our family the way the rest of the world sees us: the obnoxious teenager, pretending he doesn’t know us; the crazy jumping bean, nattering on about the A train; the frazzled, fanny-pack-sporting mother, now part of an unappetizing visual of two ancients on a booty call.

Yet I want to turn to everyone in line and say, “You should all be congratulating us. Several years ago, Hoppy over there would hardly have been talking at all, and whatever he said would have been incomprehensible. Sure, we have a few glitches to work out. But you’re missing the point. My son is ordering ham. Score!”

You may recognize Gus as my autistic son who recently enjoyed his fifteen minutes of fame. I wrote a story for the New York Times called “To Siri, With Love,” about his friendship with Siri, Apple’s “intelligent personal assistant.” It was a simple piece about how this amiable robot provides so much to my communication-impaired kid: not just information on arcane, sleep-inducing subjects (if you’re not a herpetologist, I’m guessing you’re about as eager as I am to talk about red-eared slider turtles) but also lessons in etiquette, listening, and what most of us take for granted, the nuances of back-and-forth dialogue. The subject is close to my heart—it’s my son, so how could it not be?—but I thought the audience for this sort of thing was limited. Maybe I’d get a few pats on the back from friends.

Instead, the story went viral. It was the most-viewed, most-emailed, most-tweeted NYT piece for a solid week. There were magazine, television, and radio pieces around the world. There were letters like this:

You may be aware that right now a huge effort is being made by Apple to make Siri available in other languages. I am Russian translator for Siri, and I can say that sometimes it is very hard to transfer Siri personality to another culture. You really helped me a lot to understand, how Siri should behavior in my language, with so great examples of what people are really expecting from Siri to say. And your thesis about kindness of machine towards people with disabilities just had made me cry. We had a talk about your article in our team, and it was very beneficial for general translation efforts for Siri.

So, with your help, Russian Siri would be even more kind and friendly, and supporting. I always keep in mind your son Gus, when writing the dialogs for Siri in Russian.

This letter moved me deeply, as did the hundreds of emails and tweets and comments from both parents of children with autism and autistic people themselves (not that they always identified themselves as such, but when a guy tweets different lines from your piece over and over and over, you can figure it out). I think my favorite letter was from a man who wrote to the editor: “This author has a future as a writer.”

Why did this story hit a nerve? Well, for one thing, it presented an opposing view to the current notion that technology dumbs us down and is as bad for us as Cheetos. But its popularity also, I believe, stems from its being about finding solace and companionship in an unexpected place. As we disappear into our phones, tablets, smart watches, and the next smart thing, it’s all too tempting to disengage. These days, it’s easy for everyone to feel a little lonely.

But here was a counter point of view. Technology can also bring us out a little and reinforce social behavior. It can be a bridge, not a wall.

I realized there was a great deal more to say about the “average” autistic kid. Narratives of autism tend to be about the extremes. Behold the eccentric genius who will one day be running NASA! (Well, someone has to get a human to another galaxy; you didn’t think it would be someone neurotypical, did you?) And here is the person so impaired, he is smashing his head against the wall and finger painting with the blood. What about the vast number of people in between?

That’s my son Gus.

From the book TO SIRI WITH LOVE: A Mother, her Autistic Son, and the Kindness of Machines by Judith Newman. Copyright © 2017 by Judith Newman. Published on August 22, 2017 by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

This article was originally published on December 18, 2017.

This segment aired on December 18, 2017.