Advertisement

Author Seeks To Find Out What Happened On 'The Day That Went Missing'

Resume

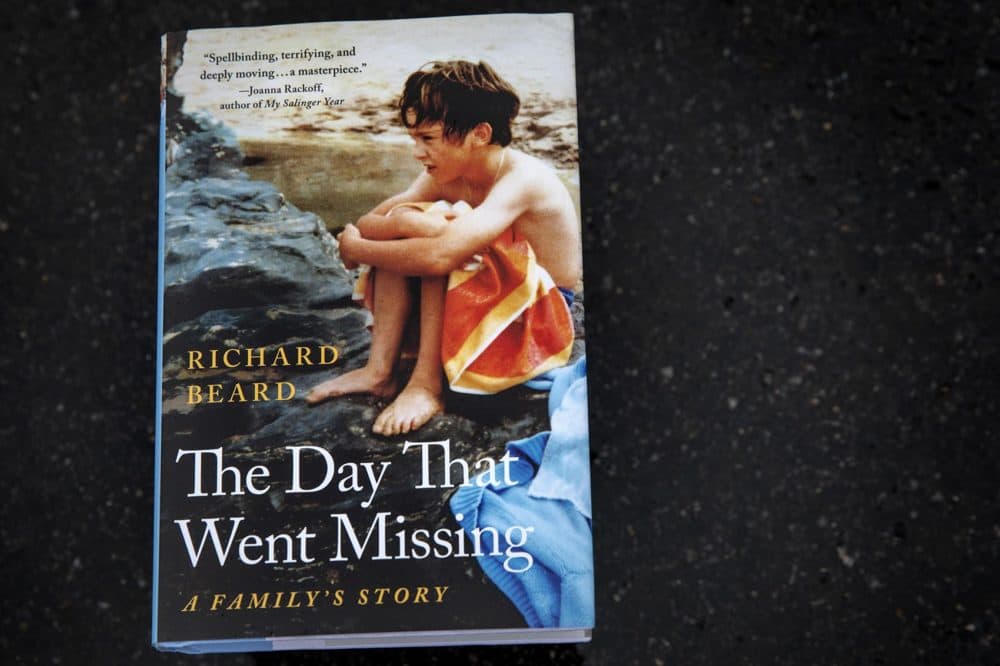

In his new book, “The Day That Went Missing,” author Richard Beard probes what happened the day his 9-year-old brother Nicholas drowned, an event which his family rarely spoke about.

Why the book is titled that, Beard explains, is because that dark day in his life went “completely missing” from his mind, as his entire family worked to eliminate nearly all memory of Nicholas.

“We had managed not to speak Nicky’s name for nearly 40 years,” Beard (@BeardRichard) tells Here & Now's Robin Young, “and in trying to delete the pain of the day that he died, we ended up deleting him as a person."

Beard says trying to bring back the memory of his lost brother was an intense experience that “required a lot of tenacity just to get through all those years of denial to try and find out the facts of what had happened that day.”

Interview Highlights

On what he remembers about the day Nicholas died

“Nicky and I went away from where everyone else was on the beach, and we found this little cove, which actually I'd seen before and I thought the waves looked great in there, and great when you're 11 means they look bigger, they look like they're going to be more fun to play in. And we went into the water, and of course, the waves were bigger, the currents were more powerful — the tide comes in very quickly on that part of the Atlantic coast — and we were very quickly out of our depth and in trouble.

"Part of the inquiry was an inquiry into myself to say, 'Why did I do that? Why did I feel this absolutely urgent need to save myself?' And I think it was because I knew that I too would die if I stayed there."

Richard Beard

“A lot of things about the day, the details and where it was and the date, all that had gone, but this one memory remained. There was this one visceral memory, which couldn't be erased, which was of Nicky in the water, this strain in his face, this terror that he was experiencing, that remained with me, partly because I was feeling it as well.

“And then of course, that decision to swim in and to leave him there. Part of the inquiry was an inquiry into myself to say, 'Why did I do that? Why did I feel this absolutely urgent need to save myself?' And I think it was because I knew that I too would die if I stayed there, but it's been a hard thing to come to terms with.”

On confronting his mother about the truth about Nicholas

“I broached the subject with her, not having spoken to her about it for over 35 years. By this stage, I had done a little bit of research, so I was ahead of her, and I knew that he was very good at sport for example, because I'd found his school reports. I knew he was good at school, because they had the records from the school that he was top of the class. And the first thing that my mum said to me was that, 'He wasn't like you. He wasn't good at sport, and he wasn't good at school, and he was going to be either a banker or a murderer.' And I was shocked that she should say this. He was very like me. And then I challenged my mum about this, about this false memory, and to her credit, immediately, she let much truer memories out. She was desperate to talk about Nicky in fact, and she'd wanted to talk about him for years. And I think our relationship gets much closer, because we find there is this one thing that we want to talk about.

"In her mind, Nicky had become a kind of black sheep of the family, who wasn't going to amount to very much, and therefore, in a way, it was okay that he was the one who died, and she'd forgotten that I was in the water with him — which she must've known at the time — as a way of not having to cope with the fact that two of her children might have died at the same time. So I understand those coping mechanisms now. … I think we all understand them better.”

On attempting to remember Nicholas in order to write the book

“One of the catalysts for wanting to write the book was my own two sons, who'd gone through the two important ages in this book, which is nine — when Nicky dies — and 11, the age I was at the time. And I remember seeing both my boys, especially the younger one … and it's like, he's 9 years old, he's a fully realized human being, he's got an interior life. All that had been lost with Nicky, so I had no sense of that human being, but I could see what a vibrant human being a 9-year-old boy is, and I just thought, 'I've got to get some of that back.'

“What I didn't know when I started was that when the real Nicky started to come back to me and I made this effort to remember our relationship, the truth of it was, we had a competitive relationship. I'm pretty sure it would have passed. I had quite a competitive relationship with my older brother, which eventually passed, and we are now very, very close. But at the time when he died, we were competitive, we were both very sporty, we would have running races and fights and cricket matches, and I quite resented the fact that he was 2 years younger than me and catching up, and in the rough and tumble of family life, I felt my place was being usurped. And all that came back, and I felt that I needed to reflect that honestly as well. ...

“Part of the problem was, I think, is that we weren't the best of pals, which made dealing with his death even more difficult in some ways, because there was a part of me, which in a childish way before he died, would have thought, 'God, things would be easier if he was dead,' which is quite hard to come to terms with.”

"That connection was now there and that ... is something that can be done generally — connections which seem unutterably broken can be remade."

Richard Beard

On those with shared experiences who have reached out to him

“I've had contact from a lot of people. It's amazing how many people have a similar experience, not necessarily a brother, but an experience of bereavement or of pain, of emotional trauma.

“Especially from that period of time in Britain, from the '60s through until the mid-'80s when I think things started to change a bit ... this experience of emotional trauma followed by the idea that an emotional response wasn't a legitimate way to deal with it — and that the stiff upper lip should be brought into into effect, and the most important thing is to move on, which means acting as normal ... before the person has died, as if nothing has happened — that seems to be a very common experience, and the book seems to have allowed a lot of people to express that to me.

“Also, in the letters and the messages, there's a sense that they now want to share their feelings, which have been hidden about this, with their family members, with the confident hope that it will make things better, that it will release that grief and really allow them to express themselves more fully.”

On the part of the book where he is asleep and dreams of Nicholas

“There's something in my subconscious which released this image of Nicky, which I could connect to and which had some kind of resolution, in the sense that we're both very alive and enjoying ourselves together. And there was a real sense of joy. I don't know, I think this is common with dreams, is that waking up from a dream and what is strongest about is the emotion that it has created. In this sense, it was genuinely joy, and it felt like a real breakthrough in terms of connecting to Nicky in a real sense and showing to me that writing the book had been worthwhile, that that connection was now there and that this is something that can be done generally — connections which seem unutterably broken can be remade.”

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Jackson Cote adapted it for the web.

Book Excerpt: 'The Day That Went Missing'

by Richard Beard

Most days, on holiday in Cornwall, the family walks to the beach. A path drops steeply, and either side wheatlike heads of wild grass grow at waist height. Some of the seeds strip away neatly between childish fingers, and some do not. Each time I scatter a pinch of seeds into the greenery, I win. I made the right choice, and at the age of eleven it feels important to be right, or lucky.

We are a family from Swindon, England, on our summer holiday to the seaside. In 1978 this is what landlocked families do: spend a high-season fortnight on the coast, in Wales or Cornwall, in search of quality time that later looks bright and simple in photographs.

The family is Mum, Dad, and four boys. I am second in a declension that goes 13, 11, 9, 6. My brother Nicholas Beard is nine. For nearly forty years I haven’t said his name, but in writing I immediately slip into the present tense, as if he’s here, he’s back. Writing can bring him to life.

On the sand at the wide Cornish beach we set up camp. Mum lays out a blanket, while we tip plastic buckets and spades from a canvas bag. We take off our trainers, stuff socks inside. The picnic is in a wicker basket, and hopefully today’s Tupperware contains hard-boiled eggs, my favorite.

The beach is huge, the sand compacted and brown. We sprint up and down, leaving crisply indented footprints, evidence that we exist with boyish mass and acceleration here, now, or verifiably just moments ago. Every year, wherever the holiday, we run faster — the prints lengthen and deepen, rows of four in races for a made-up podium.

In the sea, we jump the waves. Look, look out, here comes another. We cherish our special knowledge that every seventh wave will be bigger. We swear by our one and only fact about the rhythms of the sea, but rarely count to seven to check it’s true. Some waves are suddenly huge, not thigh- or waist-height, but up to the chest, the neck. These are the best of waves, sent from the mysterious deep to amuse us. We don’t go out farther than we can stand, and we’re not interested in swimming. The fun is in the contest against wave after wave, whatever the Atlantic’s got; we tumble for ages like apes, never feeling the cold.

At some point we’ll dry off and try a game of cricket, but coastal winds blow the ball off-line and the bounce on sand is variable. The cricket never really takes because Dad wants everyone to bat, as if life is fair. He doesn’t understand that we’re in it to win it.

What do I know? I mean what I remember, what I carry with me.

One summer day in 1978, eleven years old, toward the end of a bright seaside afternoon, I left the broad stretch of beach with my brother Nicholas, aged nine. I don’t remember why. Facing the sea, we ran to the right, away from the family camp, and clambered round or over some rocks. On the other side we found a fresh patch of unmarked sand. I see this place as a cove, with dark rocks close in on both sides, rising steeply to cliffs. The new sandy beach doesn’t reach back very far.

The two of us are in the sea, jumping as the waves roll in. Until now I have tried not to know this and many times I’ve stopped, squeezed shut my eyes and closed the memory down. I can do that, crush it out of existence. All it costs me is the effort.

We were having fun, buffeted and breathless. I can believe I know this, even though the effort to forget has been immense. The memory is in ruins, but the foundations are traceable.

He was out of his depth. He wasn’t and then he was. I can’t remember everything, not each separate moment.

I don’t know how, but suddenly he was out of his depth. I think I tried to push him back toward the shore, but the logistics are confused and I, too, am up to my neck. With my feet touching the sand my mouth is barely above the water. The instinct, because I’m not a good swimmer, is to walk back in but when I feel with my toes the sand sucks out from beneath me. The next time I try, only the tips of my toes touch solid ground. The ocean floor sweeps from beneath me. Nicky is farther out into the sea than I am, and I don’t know how that happened either. Is he?

His head is to my left as I look toward the horizon. I’m looking to him, away from land and safety, so I must be worried. He’s farther out than me and too far to reach by walking, and anyway I’m in too deep to walk. I don’t understand how he got there. I search with my foot for solid ground and my head is under and I just about touch and the sand rushes out. I push back up. His neck is stretched taut to keep his nose and mouth in the air, and he is panicked into a desperate doggy-paddle, getting nowhere. He whines, his head back, ligaments straining in his neck, his mouth in a tight line to keep out the seawater.

I couldn’t reach him and I didn’t want to go in deeper. I shouted at him not to stand. He had to swim. I shouted he shouldn’t try to stand. He tried to put his foot down and his head went under.

Out of my depth, I was about to die. Nicky was trying to stand in water that was too deep, and in any case the undertow would drag him out. I decided to leave him. A conscious decision. I kicked my legs up and launched into a desperate crawl, face submerged, no breathing, a last resort to create forward momentum toward the shore. Front crawl was the fastest stroke over the shortest distance, though I didn’t really know how to do it, and if I stopped to breathe I would die. I smashed my arms and hands into the water, head down, feet thrashing, because I understood that for me it was now or never.

Faster! Harder!

I understood with absolute clarity that I had one go at this. Run out of breath too soon and I would drown, exhausted and unable to find my footing. Keep going and I might get close enough in to stand, to live.

The memory is unsatisfactory. I experience the pain of remembering though I can’t clearly remember. I was going to die so I decided to save myself, and staying alive took total concentration. I swam my frenzied approximate crawl until finally I had to breathe, and when my legs dropped down, my feet touched sand. The sand dragged me out, but I was far enough in to fight the undertow. I swam again, until I needed to breathe again. Chest-high in the water, waist-high, the sea was around my thighs and I could almost run, heaving my hips one way then the other, driving hard toward land, knees raised, escaping the water.

I don’t remember looking back, or arriving at the camp on the main stretch of beach. I’m out of the water and running. I see a man. He is higher up, on rocks (or on a path above the rocks?). I tell him ... I don’t know what; whatever I said isn’t part of what I know. I communicate the situation and the man stands up, gazes out to sea as if primed to make a decisive intervention. He takes off his sunglasses, and in a purposeful gesture hands them to the distressed and dripping boy.

I’m running again, to the right, over patches of hard sand between flat rocks, from one terrain to another. I remember looking down on myself, as if from above, running with the stranger’s metal-framed sunglasses and finding them an absurd responsibility to have accepted. I throw his stupid sunglasses to the ground and they smash on hard rock and I don’t care. I’ve broken an adult stranger’s sunglasses, intentionally, and I don’t care. I’m crying, I’m running. My face is out of control.

And that’s about it. Of the incident itself, that’s close to all I know.

My younger brother’s name is Nicholas Beard. He was nine years old, and I was with him in the water when he drowned. Events that happened before and after are a blank to me. I don’t know the name of the beach in Cornwall where he died or the date when the drowning took place. I’m not even certain of the month.

Excerpted from THE DAY THAT WENT MISSING Copyright © 2018 by Richard Beard. Used with permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York. All rights reserved.

This segment aired on November 26, 2018.