Advertisement

What One Bioethicist Learned From Becoming Dependent On Opioids — And Weaning Himself Off

Resume

After a motorcycle accident that almost took off his foot, Johns Hopkins University bioethicist Travis Rieder became dependent on the pain medication he had been prescribed.

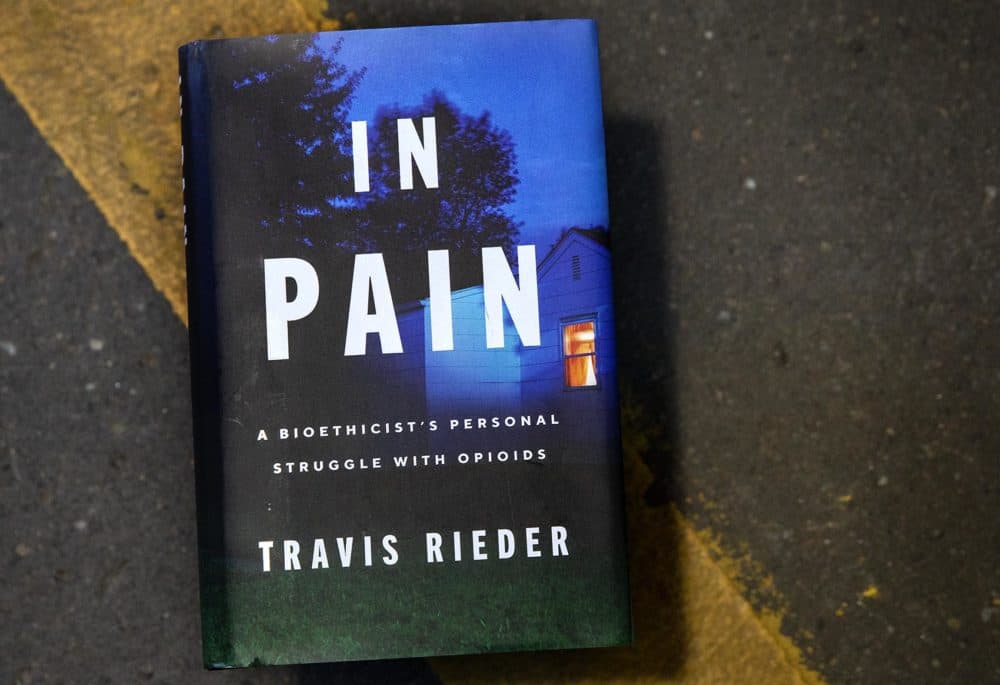

Though he managed to wean himself off the drugs, the experience prompted him to write the book "In Pain: A Bioethicist's Personal Struggle with Opioids."

Rieder (@TNREthx) raises important questions about the ethics of prescribing such highly addictive drugs, and he quotes researchers who found there is little to no formal training in pain or pain management in U.S. medical schools. In fact, veterinarians in Canada have more education in pain than U.S. medical students do, according to research cited in the book.

After his 2015 accident, Rieder says he was prescribed a number of opioid pain medications, which he needed to deal with the pain. But he says no one told him how to manage the addictive nature of these drugs.

"Nobody talked to me at all. And that's really a huge part of the failure because I was in such severe pain," Rieder tells Here & Now's Robin Young. "It's hard to believe that I was really overprescribed in a really direct sense. What happened more is that they probably gave me too much for too long because nobody was talking to me, no one was managing me."

Rieder says he hopes his story prompts more medical schools and hospitals to better train doctors on how to properly prescribe these drugs and manage their use.

"We still require opioid pain relief because they are so so powerful, especially for post-traumatic circumstances, post-surgical circumstances, and ... more rarely, but still sometimes, for really severe chronic pain that's closely managed by an expert," he says. "So this is not a story of, 'These drugs are too deadly or too dangerous to touch.' "

Interview Highlights

On his accident and the injury to his foot

"I got hit by a van on my motorcycle, and my foot was crushed between the van and the motorcycle, and then the motorcycle landed on it again. The bones shattered and kind of blew their way out of the foot. And so that soft tissue damage that resulted from all those shattered bones put me in what's called a limb salvage situation. So it was very unclear whether they're going to end up amputating or not."

"I work with physicians, and it's still just not enough education and not enough clinicians understanding that they have to really take ownership of this process."

Travis Rieder

On what his doctors did tell him about taking the drugs

"All they said is, 'Don't get behind the pain.' So I kept watching that clock and kept taking the medication because I desperately wanted to stay ahead of that really severe terrible pain. No one said, 'Hey, think down the road about this.'

"Opioids have this property that you develop tolerance to them, and this is just part of the normal biological process, and so you require a higher dose to achieve the same analgesic effect. Doctors know this, and so if you're going to be on them for some amount of time — which I was because I had five surgeries over four weeks — they just expect to have to increase the dose fairly regularly. And no one batted an eye as I kept upping the dose of oxycodone.

"It's hard to believe and hopefully it's still getting better that there's more realization. But I work with physicians, and it's still just not enough education and not enough clinicians understanding that they have to really take ownership of this process."

On what his orthopedic surgeon said about the drugs at his three-month checkup

"The orthopedic trauma surgeon was concerned enough that we were concerned about what was to come. But then we ... went to the plastic surgeon who'd been prescribing, and he just wasn't that worried. He said, 'Oh, just cut your dose into four and drop a quarter of your daily dose each week and you'll be fine.' "

"I describe it as having the worst flu you can imagine. You get sweaty, you get goose flesh, you get nauseated, you start tearing up."

Travis Rieder on withdrawal from opioids

On what happened when he tapered the dosage as his doctor prescribed

"It's far too aggressive. We didn't know that at the time, and oxycodone has a short half life, which means it cycles out of your system pretty rapidly. So that first week, you know, I describe it as having the worst flu you can imagine. You get sweaty, you get goose flesh, you get nauseated, you start tearing up. You know, you shake, you get jittery, you get restless. Basically, the symptoms of withdrawal are the opposite of the symptoms of the drug that you're on.

"It's what I came to call 'the withdrawal feeling' because you know, sedation is an aspect of opioids, and so when you go off of opioids, the kind of opposite sensation is you've got this energy kind of building up in your core, and you feel like you have to release it. And what that means is you can't sit still and you can't sleep and your legs kick in, your arms twitch. And the higher the dose drop you go through, the less you sleep."

On what happened when he reached out to other doctors for help

"Nobody knew [what to do]. And so the guy who did the actual prescribing, I believe that he didn't know because he was a very compassionate person, and he would speak with us on the phone, and he just eventually admitted that he was out of his depth and he apologized. But a lot of physicians, you know, we called every prescriber, more than a dozen that we'd had in three different hospitals, we called anyone we could find on Google. And most of them wouldn't even speak with us, and so who knows whether they didn't know or they just thought, 'Not my problem.' "

On when he reached his breaking point during withdrawal

"It got so bad I started to think, 'I might have to kill myself. I'm never going to get better.' And it got so bad that we eventually decided to go back on the medication, and I absolutely would have, and [my partner] supported me in that decision. But the night that I decided to go back on the meds — she went and got a new prescription for me — that night I happened to be able to fall asleep. And when I fell asleep, I kind of broke through the last of the worst symptoms and when I woke up, I thought, 'OK, I can do this.' "

On the lack of training for doctors on pain medication and management

"We have taken pain and pain medicine to be relatively easy to treat. You didn't need a lot of training in it. And then the other side of it, the eventual really scary downstream side for the people who develop an addiction, that's a really stigmatized condition. A lot of doctors don't want to deal with that. So we don't think a lot about pain, and we don't want to think a lot about addiction. And so these people who turn from pain patients into patients who have a dependence and go into withdraw and then are then at some risk of developing a full-blown addiction, they're just the hardest patients to deal with for a medical establishment that's not set up to deal with them.

"I work with a lot of hospitals and universities and I speak with doctors and systems that are interested in changing. I lay this out, and when you have partners who came to the table ready to work, these problems are solvable. And some systems and hospitals and organizations are working towards it, but not everyone's listening yet and that's why I still work on it."

On the lawsuits against the manufacturers of these opioid drugs

"There were very clearly, we now know, some very bad players in pharma, and I think it's really important that we hold them accountable. But we also just need to do a whole bunch of other things to make sure that people who need addiction treatment get it, and we need to restructure our health care system. Those things have to happen independently of how much we want to blame certain bad players."

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Tinku Ray. Samantha Raphelson adapted it for the web.

Book Excerpt: 'In Pain'

by Travis Rieder

When I was treated with suspicion by the attending ICU doc after my free flap surgery, I was hurt, ashamed, and, eventually, livid. I felt wronged by the physician, and it would be a long time before I could articulate the kind of wrong that I had experienced. But now I think I understand: the doctor had disrespected me in a very specific way, by not taking my words—my testimony—seriously. I told her that I was in pain, and by treating that claim as if it were the kind of thing that she should check on—because I was unreliable and might be trying to get drugs—I was denigrated in a way that I hadn't remembered ever experiencing before.

But here's the thing: the very fact that I could be surprised—no, shocked—at this doctor's ability to disregard my testimony reveals my privilege. Because as those in less powerful social positions know well, the experience of not being heard or taken seriously is a part of many peoples' daily lives. There is even a term for it in the academic literature: “epistemic injustice” is the experience of not having one's testimony taken seriously due to being part of a particular group.

As a white man, I had gone through my life with the invisible (to me) privilege of largely having my claims taken seriously and my position at the table acknowledged. When I became a pain patient, I—perhaps for the first time in my life—became part of a group that is stigmatized and marginalized. Because pain is subjective, it's al-ways been suspicious; after all, if there's any reason at all to “fake” pain, then patients have a reason to deceive doctors. And in the era of opioid plenty, there is a ready-made reason to feign pain: to get those good drugs. And so I, now a pain patient, was part of a group whose testimony is taken to be unreliable.

But of course, suspicion is not distributed evenly. Sure, pain may be a stigmatized condition, but some of us bear one such stigma, while others bear many. With all of my privilege due to race, gender, profession (recall that the one resident who referred to me as “Dr. Rieder” rather than “Mr. Rieder” is the one who got the ball rolling on my pain management consult), and likely much more, I managed to go through my entire hospitalization encountering suspicion only very rarely. That is, unfortunately, not everyone's experience.

Over the last couple of decades, research has demonstrated that white and black patients are treated differently when they com-plain of pain. A 2012 analysis of published data showed just how serious the disparities are: not only are black patients 34 percent less likely than white patients to be prescribed opioids for those “nondefinitive” conditions, but they are also 14 percent less likely to be prescribed opioids for traumatic and surgical pain. In other words, the pain of black patients is treated less aggressively across the board, both in contexts where the physician may suspect them of lying and also in contexts where their pain is undeniable.

Another recent study tried to explain why these differences might exist, and the results were appalling. The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences in 2016, showed that a shocking number of people—including medical students and resident physicians—hold false beliefs about biological differences between black and white people. The survey asked subjects to say whether they believed a series of claims, including the false claims that “blacks' nerve endings are less sensitive than whites' ” and “blacks' skin is thicker than whites'.” Although relatively few of the medical students and residents endorsed the first claim (although some did), many endorsed the latter; in fact, a full 25 percent of res-ident physicians reported believing that blacks' skin is thicker than whites'. Even more distressing, physicians and medical students who reported more false beliefs about biological differences between the races systematically rated black patients as experiencing less pain than white patients and recommended less aggressive pain treatment. Basically, having false beliefs about the difference between races led students and physicians to undertreat the pain of black patients.

The disparity in opioid therapy even extends to children. In a 2015 study of pain management for children with appendicitis, black children with moderate pain were less likely than white children with the same level of pain to receive any pain treatment. And among all of those with severe pain, white children were more than twice as likely as black children to receive opioids.

Nor does the unequal treatment of pain only apply to black and white patients. Hispanic patients are also systematically prescribed fewer opioids than non-Hispanic whites, and there is significant data to suggest that women are less likely to have their pain aggressively treated. In a 2001 paper, Diane Hoffmann and Anita Tarzian showed that women are less likely to have their reports of pain taken seriously and to be prescribed opioids even though women have more incidence of severe chronic pain than men.

A critical point about my story, then, is that it is undoubtedly skewed. My brush with undertreated pain and being treated as a drug-seeker was maddening, but it was also minimal. Indeed, the de-fining lesson of my personal story is the degree to which pain can be treated in a truly aggressive fashion. But replace me with a black man or a Hispanic man or a woman, and my experience likely would have been very different.

This realization helps to put the Opioid Dilemma in an even more complex framing: not only do physicians struggle to avoid the dual burdens of undertreatment of pain and overuse of opioids, but those burdens are not evenly distributed across the population. White men are best positioned to have their pain taken seriously, which raises serious concerns about both the pain treatment of minority patients as well as the respect they are given by clinicians. Having one's pain undertreated is bad enough due to the outcome (still being in pain); to know that it's because of one's race or gender adds the insult of injustice to the already existing injury. Further, the recent increase in opioid use disorder among white communities is also now suddenly less surprising. In this case, the privilege of having one's testimony taken seriously has come with a cost: treating the pain of white patients in a disproportionally aggressive manner has led to a similarly disproportionate increase in white patients with opioid use disorder.

From the book: IN PAIN: A Bioethicist's Personal Struggle with Opioids by Travis Rieder. Copyright © 2019 by Travis Rieder. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

This segment aired on June 24, 2019.