Advertisement

250 Years Ago, Captain Cook Embarked On First Of Three Voyages

On this day 250 years ago, Captain James Cook was about to leave the island of Tahiti in search of a lost continent known as Terra Australis.

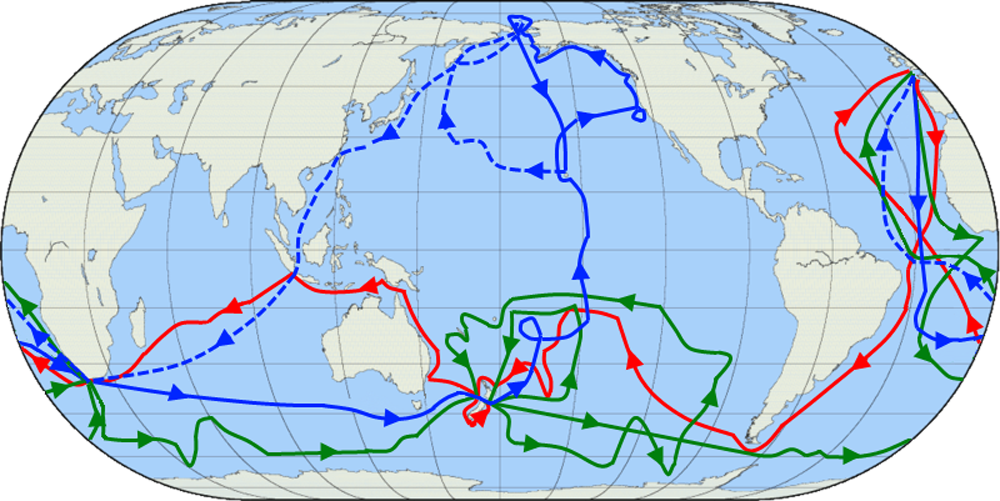

Cook had been sent to the region by the British admiralty, first to observe the transit of Venus and then to find the storied continent. This was the first of Cook’s three voyages, which all lasted for years.

When all was said and done, Cook ended up dead on a beach in Hawaii, but he lives in memory as one of the greatest explorers in human history, particularly for his map drawings.

In terms of explorers of the world, “he's not far off the top in terms of what he achieved and how much he completed the map of the world considering what was available to him in the late 18th century,” says Cliff Thornton, who is a member of the Captain Cook Society.

“I remember there was a French explorer who was gonna go out and somebody said, 'Well, what are you going to do?' And he said, 'I don't know. Cook's done it all. There's nothing left for me to find. I don't think,' ” Thornton tells Here & Now’s Jeremy Hobson. “So you got the map of the Pacific, which many people said, 'We don't need to build a memorial to him. That serves as a as Cook's memorial.' ”

But Cook’s legacy is a complicated one, Thornton says. He is often criticized as a “colonizer” and for the impact that the European perspective had on some of the Indigenous cultures, but Thornton says Cook’s writings show he was actually empathetic toward the native people he encountered.

“There was a sort of empathy coming across in there as well,” Thornton says. “He comes across as very much a humanitarian.”

Interview Highlights

On the places Cook discovered for the Europeans

"Some of the places had been previously visited, such as he went to Tahiti to take some astronomers to do the transit of Venus that had previously been visited by another English captain. He also went to New Zealand, but that had been visited by Abel Tasman some 60 years previously. He did visit Hawaii, but some say the Spanish had been there before him. So there are a host of other of the smaller islands and groups of islands like the Society Islands. You lose track of them. There's so many of them. When he started out, the Pacific Ocean was really a blank canvas. And by the time he'd finished, there were islands here, there and everywhere that he'd mapped and often drawn detailed charts for them."

“Cook's ships were often a bit like a Noah's Ark. There were so many animals on them."

Cliff Thornton

On his first trip to Tahiti where he met his navigator, Tupaia

“Well, the first place he went to was to Tahiti, and he was fortunate there because a Polynesian priest came to him and said, 'Look, I'd really like to travel with you. I know all this area. I can tell you where the islands are. I can help you navigate there, and I can help translate.' His name was Tupaia. And he really, he was worth his weight in gold. I don't think Cook could have achieved what he did if it hadn't been for Tupaia. Whenever he got to a new island, he would lead Cook ashore. He would say, 'Sit on the sand. Take your shirt off. I'm just going to make a speech.' And Tupaia made the speech to the local chief and established peaceful relations, and he went from there.

“When Cook got to New Zealand, it was Tupaia who spoke to the people. And they understood him, even in New Zealand because the Māori of New Zealand originally are said to have come from Tahiti.

“And the funny thing was when Cook went back to New Zealand on the second voyage, the people said, 'Where's Tupaia?' Unfortunately, he died when he caught a disease ... on the way home.”

Advertisement

On the impact of the animals Captain Cook’s team brought on these voyages

“Cook's ships were often a bit like a Noah's Ark. There were so many animals on them. Some of them they took along for let's say, feeding the crew, but primarily they were presenting to the chiefs of the islands where they visited to say, 'Look here, have these animals, and they will breed if you look after them right.' And because they were the chiefs, no one else on the island would interfere with them. So he did that and whenever he stopped, he would try and find a little piece of ground that he could till and plant some seeds to see if European species would grow there. So that if he was coming back another year, who knows there might be a crop waiting for him. Some of the animals, he had so many chickens, he let a few loose — let's say in Queen Charlotte Sound on New Zealand — and he hoped that they would breed in the bush. I'm not sure whether they survived, but certainly the goats that he released there certainly exist today. In fact, the New Zealand government [has] said they don't care they've been there 250 years. They're an alien species. ‘We want them eradicated.'

“I don't think he directly would have had any impact on wildlife. I mean, the naturalist on board wanted samples, so they might have shot a few birds, caught a few fish, some fish would have been caught to feed the crew. But I don't think he really had an impact on the wildlife. It was those who came after him. It was the settlers who wanted to take a few animals from home.

You look at Hawaii. Poor old Hawaii suffering tremendously from the number of alien species there, one of which is the little sparrow from England. Somebody must have taken it out because they wanted a sparrow there. There's probably more sparrows on Hawaii than there are in England now. They're in decline over here.

And then you've got somebody like Vancouver, who traveled with Cook on the third voyage. He went back to Hawaii in 1793 and presented the king with a couple of ... cows and said, 'Let them breed and you'll have a good herd.' And by 1830, there were hundreds. The problem was they'd been just left to roam about on the hillside of Mauna Loa, the volcano, and they decimated the wildlife, taking with them many of the species that are no longer there.”

"This was a 42-year-old sailor. He speaks like a sociologist."

Cliff Thornton on Cook's writings

On the criticism of Cook as a “colonizer”

“I wouldn't call him a colonizer. He was a visitor, and he was a regular visitor at some of the places like New Zealand. He was there for every one of his three voyages. And the benefit of that was that he could see how the people changed from his first visit in 1769, 1773 I think, and then 1777. And it wasn't a good change.

“And if there was one impact that it had on all of the people, it was they discovered that the British had iron. There's no natural source of iron in any of the Pacific Islands. It was almost a stone-age existence. If you wanted to cut something, you used sharpened stone or you used an edge of a shell. And so to actually say, 'Look, here's this metal that you can sharpen, you can get a blade on.' And so by his last visit, Cook actually recorded in his journal that the people had become more greedy for the metal. They wanted it so much they would prostitute their wives or their daughters just to get some metal off the sailors, and they were thieving from each other stuff that had never existed before.

“And so Cook saw that and he was disappointed that what he thought he would bring as benefit to the islanders was actually leading to a deterioration. And the same when he took some iron hatchets out on the second voyage. He'd seen they had hatchets made of stone, so he took some iron hatchets out. 'Here well, lads,' he said, 'you can chop the trees down with these.' When he went back on a third voyage, they were using those same hatchets for attacking each other. That's not what he wanted.”

On the detailed notes Cook took on his voyages

“He wrote down the day-to-day events and then whenever he had finished a visit to an island ... he would summarize at quite length the description of the peoples — how they dressed, what they spoke, a glossary of their words sometimes — and a description of the land — whether it was rocky, whether the soil was good, whether it would support crops — and then he wrote down about the demeanor of the people.

“And as he went around the Pacific, he met people in vastly different stages of what you would say, civilization for want of a better word, and Tahiti, you had a social hierarchy, but the people lived in pretty plain huts and a pretty simple lifestyle. When he got to New Zealand, there [were] far more structured social positions, they lived in large houses with these highly decorated faces to them, and so they were far more advanced compared to Tahiti. Then he came to Australia and found the Aborigines leading almost a nomadic existence, surviving under pieces of bark for shelter. ... Here let me read what he wrote because it's hard to believe that he wrote this. This is about the Aborigines in Australia:

The natives appear to be the most wretched people upon Earth. But in reality, they are far more happier than we Europeans being wholly unacquainted not only with the superfluous, but the necessary conveniences so much sought after in Europe. They are happy in not knowing the use of them. They live in tranquility, which is not disturbed by the inequality of condition. They set no value upon anything we gave them, and nor would they ever part with anything of their own.

“This was a 42-year-old sailor. He speaks like a sociologist.”

On how sailing with no sonar almost led to Cook sinking his ship

“I think he was aware that as he was sailing north along the coast of the east coast of Australia, he was aware that there were reefs there, and sometimes they would anchor overnight, so there was no risk of running into them. But … if there was too much depth to anchor, he went on at a slow speed. And it was in the middle of one night where he actually bumped into an isolated reef now called the Endeavour Reef near Cooktown in Queensland.

“It was quite a bad leak, and the water was coming in, so he set the crew to the pumps to pump the water out and the water was gaining. So he had to lighten the boat as quickly as he could. And the heaviest things on board were the cannon and there were four cannon on the deck. He threw them overboard. He had a couple of cannon down below. He threw those overboard. He even took the ballast ... down in the hole that kept the ship stable. He even took the iron ballast out and threw it overboard. And you know all those things were recovered 200 years later.”

On what Cook achieved from a mapping perspective

“It's absolutely incredible that they could produce such a detailed map with what was called the running survey, which is sailing along, taking your bearings, plotting on the map and sailing a little bit further, and crossing with other points that you saw on the land, using your angles, using your sections and the plain table that he had on board and producing that map. And that map existed until we sent satellites up, and we could get an accurate picture of New Zealand from space.”

On how Cook figured out a cure for scurvy

“Well, they didn't know what the cure was or what the cause was. They just knew that after three weeks after leaving shore, if you didn't have any fresh greens, etc., you would start to show these terrible signs of scurvy. And it is often pointed out that the great battles that were fought with the Royal Navy, more men died of scurvy than died during the battles. It's that bad. Ship sailing, let's say that the Dutch East India Company, sailing around to the East Indies would weigh over-crew their ship simply because they knew a third of the men would die on the way with scurvy.

"So Cook's voyage on Endeavour, his first expedition, it was filled with all manner of suggested treatments to cure the scurvy, and he came back after three years — three years at sea — he hadn't lost a man to scurvy. He'd lost them to various diseases that they contracted. He'd lost one of the Marines overboard when he got drunk and jumped, but he hadn't lost a man to scurvy, and the Royal Society gave him a medal for that.

“The truth was I don't think he knew what had actually stopped it. He had so many different remedies on board, one of the most famous being sauerkraut — pickled cabbage. The men weren't too keen on sauerkraut, so Cook told the ship's cook, 'Dress some sauerkraut and put it on the officer's table every day and say, 'This is for officers only.' And it was a little bit of psychology and it worked. Of course, the men said, 'Hey, we want that,' and they ate it, and maybe that kept the scurvy away. But that the thing was that by curing or keeping scurvy away, he had more time in the Pacific to explore. Previously, going across the Pacific was an exercise in survival. But once he'd got around the scurvy, he could stop at islands, collect more fresh fruit and vegetables, and keep going like that. It was wonderful.”

On Cook’s tragic death in Hawaii

“It's a long sad story. He'd had a successful visit to Hawaii, and he set off to continue north to the Bering Strait again, but the ship sprung amast and he had to return. He came back to Kealakekua Bay, which was where he'd been before, and the people ... the people didn't welcome him so much. It's said that he'd come back at a different series when a different God was in favor. Okay, he could live with that. But he didn't like them stealing one of the ship's cutters that was on a piece of rope he had behind the ship. It disappeared. They got it one morning. It wasn't there.

“So he did what he'd done successfully throughout his previous career where there was an issue. He invited the local chiefs to come on board. And then he kept him on board until things were righted and runaways were returned or things that had been stolen returned. So he invited a local chief to come on board, and the chief was walking along the coast to get on his boat, and the people said, 'Don't go chief! Don't go!' And the chief sat down, and people came from the other side of the bay and said, 'Look, things, bad things are happening. Don't go with this man.'

“And Cook had, I think, six or nine Marines with him. They formed up along the beach, and suddenly a hail of stones came over from the people, and Cook saw one of the natives advancing to him and fired one of the barrels. He had a double barrel blunderbuss type of thing. It had small shot and it didn't have anything. The small shot just bounced off the ... cape. This man thought, 'Hey! [I’m] shot and I'm not being killed.' And it just emboldened them, and I'm afraid they attacked the shore party. The Marines fired, but you know how long it takes to reload one of those long muskets. They were all over them, and they just run for their lives to the boats. And of course Cook, believe it or not … he couldn't swim right. He was left on the beach and he was attacked, and he was drowned there.”

Chris Bentley produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Todd Mundt. Samantha Raphelson adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on July 8, 2019.