Advertisement

Dance Icon Twyla Tharp Says Keep Moving — No Matter How Old You Are

Resume

Twyla Tharp isn’t done moving.

The 78-year-old dance icon has created more than 150 dances for her own company as well as the New York City Ballet, the Paris Opera Ballet and the Danish Ballet.

She choreographed the films “Hair” and “Amadeus,” won a Tony Award for the Billy Joel musical, “Movin’ Out,” picked up two Emmys and countless other awards. And she’s still going.

When Tharp is waiting for the subway in New York, she’ll go over dance routines with subtle movements, a process dancers call marking. She advocates for taking the stairs and says we should take up space and push against things by doing isometric exercises.

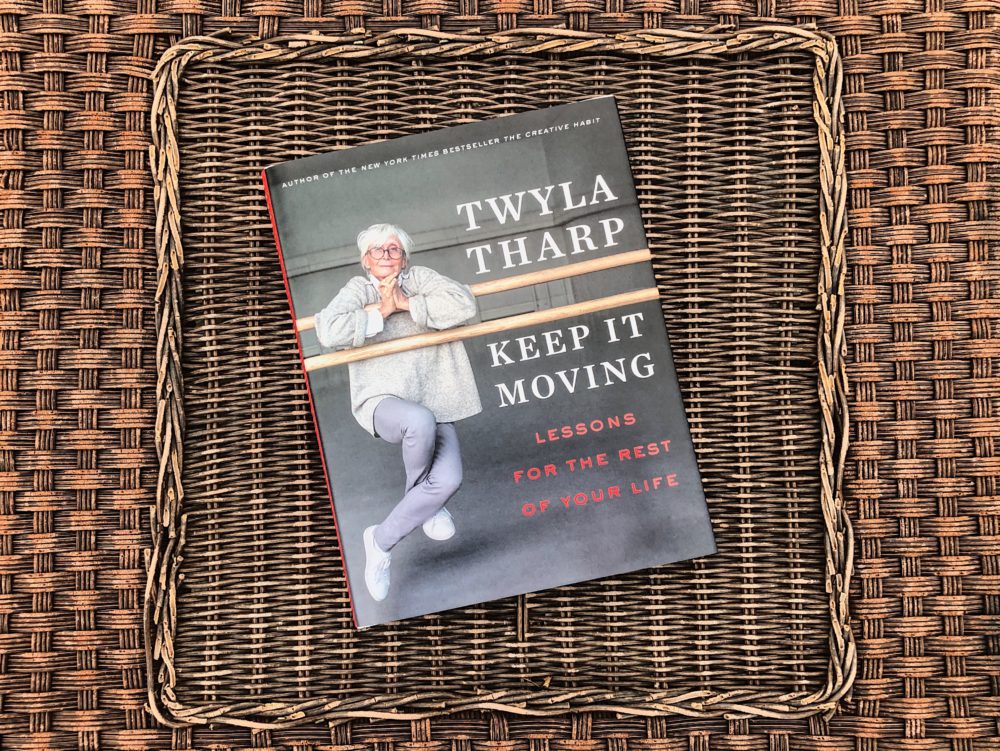

Tharp is also fighting against the notion that getting older obligates us to recede, and she writes about all of this in her new book, "Keep It Moving: Lessons for the Rest of Your Life."

“You want to know what your body can do. You don't want to ask if it's something that it's incapable of, but the only way to know what you can do is to try,” she says. “There may not be a great deal of strength in the body. There may be a lot of pain in the body, but the body can still move against itself and have some indication that it is alive and that from there it can move forward.”

Tharp, whose morning routine includes marching to John Philip Sousa, says curiosity is what keeps her moving.

“I find nothing to be worse than the restlessness that comes of feeling bored,” she says. “So I keep wanting to ask even very small questions.”

Interview Highlights

On why we all should do isometrics

“Find another object, anything, a wall, the floor and just push as hard as you possibly can for as long as you possibly can. It's a resistance exercise. It's the basis upon which all calisthenics operates, and it is … a measure of the simple fact that you will find obstacles no matter what age you are. But that the body, if it's tended, is going to do better with those obstacles than if you just let it go its own way and hang out in a corner somewhere and not exercise.

“The little moves become big moves and big moves become little moves. I think that's one of the problems. A lot of folks wait for when they know exactly how to do something or when they're an expert or competent. ... You might as well start somewhere like here and now.”

On when she auditioned for the Rockettes as a young dancer

“They say, 'Young lady, you really dance very well’ — indicating, ‘You can have this job’ — 'but could you smile?' And [that] indicates to me that really, I don't want that job. That to me is an imposition on what one really has of your own, which is your intention. What is your intention? Now it is also true the Rockets are in the business of entertainment, and that for the most part, the public would rather see happy people on stage than not happy people on stage. OK. Somehow at a young age, I did not understand those dense, complicated maneuvers and just decided this was not a life that I wanted to pursue. It was up to everybody else on their own time to figure out whether they wanted to smile or not. I was not going to tell them that.”

On fighting the human tendency to sit still

“Look, I say it in many different ways, many different times in the book: We're lazy. We all are lazy. It's a part of being a human being. And it takes an effort, it takes a conscious effort, to continue moving forward and demanding a little more space than taking a little less space. OK. It's a crowded bus. You gotta be careful about the elbows, and people are packed in. That's a different thing. But you don't want to get frozen in that position and get on a bus that isn't so crowded, then you can expand. But we forget to do that. Our bodies have remembered the course of least resistance: Work less. No, work more.”

On why moving can help you feel better as you age

“A friend of mine came this morning and she’s having a little difficult time and she said, 'I don't feel so well. I feel this. I feel that. I feel, feel, feel.' I said, 'Forget it with the feeling. Go do. Go do something.' Do will soon replace the emptiness of feeling and being out of control. Feelings are out of control and go do something. You know, go wash a pan, go grow a plant.”

On visualizing your goals and taking it one step at a time

“Mindful is a big word. Planning is perhaps more mundane and pragmatic. It's simply having the nerve to visualize the endpoint you want to accomplish, not accepting that it might fail. Assume no. It is going to be as I see it, and then visualize every single move that is going to be necessary to accomplish that.

“It's part of the notion that no pledge becomes a goal. That a pledge is an ongoing pursuit and that it's accepted that guess what? You're never going to win. You're going to be always on the pursuit of winning, but it will never happen to you. You will never have to be a winner because then actually, ironically, in a way, when you win, you're done and you're dead. So, you know, just keep working towards the goal, but never expect nor accept that it's been accomplished.”

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Tinku Ray. Samantha Raphelson adapted it for the web.

Book Excerpt: "Keep It Moving"

By Twyla Tharp

Twenty years ago, I wrote a book called The Creative Habit, sharing the message that we can all live creative lives if only we could stop waiting for a muse to arrive with divine inspiration and instead just get down to work. In other words, you too can be more creative if you are willing to sweat a little. This message still resonates when I lecture. But, interestingly, the question I am most often asked after a talk these days is on a different topic entirely: “How do you keep working?” The subtext here, sotto voce, is “. . . at your age?” Which is seventy-eight.

To me it is simple. I continue to work as I always have, expecting each day to build on the one before. And I do not see why I should not continue to work in this spirit.

Keep It Moving is intended to encourage those who wish to maintain their prime a very long time. Like most books of practical advice, it identifies a “disease” and offers a cure. That disease, simply put, is our fear of time passing and the resulting aging process. The remedy? The book in your hands.

I flirted with the idea of calling this book The Youth Habit. I liked the suggestion that youth’s virtues could be easily transplanted into our post- youth years if only we followed a routine: take the stairs, use sunscreen, ingest more omega- 3s and fewer omega- 6s, don’t shortchange yourself on sleep. Cut out sugar, do something nice for someone else daily, floss, read more, watch less, love the one you’re with, and it’s okay to drink wine (until the next study says it isn’t). Sounded like a bestseller to me.

But if experience has taught me anything, it’s that chasing youth is a losing proposition. There’s little benefit in looking back, at least not with yearning or nostalgia or any other melancholy humor. To look back is to cling to something well over and behind you. We don’t lose youth. Youth stays put. We move on. We need to face the fact that aging will happen to us along with everybody else and just get on with it. Growing older is a strange stew of hope, despair, courage—still I think you will agree—it is light- years ahead of the alternative.

I don’t promise eternal youth in Keep It Moving. I have no interest in sugarcoating the aging process. What I believe in is change and the vitality it brings. Vitality means moving through life with energy and vigor, making deliberate choices and putting to good use the time and energy that we have been granted. You have, no doubt, seen people in their late seventies or even into their nineties who don’t seem worn out by their years but instead welcome the opportunity to be truly present in their bodies and in their minds. Instead of stubbornly staying on known paths, afraid to stray, they look at what comes next with curiosity, expanding into whatever it may be.

So, no, this book is not The Youth Habit. Nor is it The Creative Habit— which promotes regularity in living and working—because as we grow older, it is just as important to break habits as it is to make them. I want to reprogram how you think about aging by getting rid of two corrosive ideas. First, that you need to emulate youth, resolving to live in a corner of the denial closet marked “reserved for aged.” Second, that your life must contract with time. Let’s start by breaking some old thought patterns.

I’ve danced my entire life (and still do) and I’ve spent time with many great performers. For these dancers and athletes, the passage of time presents mostly difficult realities. The jump declines, speed diminishes, flexibility is challenged. And fear of decline and irrelevance starts early.

Years ago, I was sitting in a coffee shop with a dancer of remarkable talents, Mikhail Baryshnikov. We had just finished one of the early rehearsals for Push Comes to Shove, a ballet I wrote for him. Even then it was clear that he was a phenomenon, one of the very greatest classical dancers of the twentieth century. Though he was in his prime, he was looking morose as we drank our coffee. I asked him, “Misha, what’s the matter? You don’t like what we’re doing?” No, he said, he loved what we were doing; “But,” he added, “soon we will be old.” He was all of twenty- seven. And yet I understood.

For dancers, aging is ever in front of us as we work. We face it each time we enter the studio, one day older than the day before. But who among us in the civilian population has not shared the feeling that they, too, will be finished by forty? It needles when things don’t work the way they used to. And it doesn’t help that, gradually, as joints begin to ache and memory to slip, we are bombarded by negative messages from our culture. Older adults are frequently portrayed as out of touch, useless, feeble, incompetent, pitiful, and irrelevant. Sadly, these dismal expectations can become self- fulfilling, creating the bias that fuels our roaring age industry—pills, diets, special cosmetics, surgery—all promising to send time reeling backward. But no. Time goes only one way: forward.

The result? Frustration becomes a habit. Little indignities become a reason to rant and complain. But that scenario will bleed out your spirit, take away your resiliencies. If you go into situations always expecting to be cheated or deprived, you’ll likely find ways to tell yourself that is exactly what has happened. Don’t go searching for things that confirm or fuel your sense of indignation. It will become a default mind- set promoting more of the same.

Let’s agree:

Age is not the enemy. Stagnation is the enemy. Complacency is the enemy. Stasis is the enemy. Attempting to maintain the status quo, smoothing our skin, and keeping our tummies trim become distractions that obscure a larger truth. Attempting to freeze your life in time at any point is totally destructive to the prospect of a life lived well and fully. All animate creatures are destroyed when frozen. They do not move. This is not a worthy goal.

However, the forces that create inertia in our lives are difficult to resist for they are hardwired into us. People prefer to keep going along as they always have rather than make a decision that would knock them out of their groove, even when it would be relatively easy to change course. Behavioral scientists refer to this as status quo bias. We succumb to this bias with habits large and small, from an inability to give up our three cups of coffee a day to staying with a partner long after it’s clear that the relationship is over. The devil best known becomes our buddy.

Along with status quo bias, there is another habit I’d like to undo. As we get older and our bodies enjoy less natural freedom of movement, we tend to take up less space, both physically and metaphorically. Here’s the endpoint of this tendency: our backs arch forward, no longer straight and long. Our steps shorten from a stride to a shuffle. Our vision narrows, slowly erasing the periphery, leaving only what’s in front of our nose. No wonder we prefer remaining at home, our life lived in fewer and fewer rooms. We let our bodies constrict, inviting the world around us to close in.

The mind will follow the body’s contraction. On this path, our concerns narrow down to the most elemental functions: what to eat, getting enough sleep, keeping an appointment.

Contraction is not inevitable. You can resist and reverse. Now to form some new habits. I hope in these pages to get you to wake up and move more. After all, I repeat, to move is the provenance of all living human beings. And by my definition, to move is to dance. With the time you’ve got, choose to make your life bigger. Opt for expression over observation, action instead of passivity, risk over safety, the unknown over the familiar. Be deliberate, act with intention. Chase the sublime and the absurd. Make each day one where you emerge, unlock, excite, and discover. Find new, reconsider old, become limber, stretch, lean, move . . . I say this with love: shut up and dance. That was the advice I gave myself for my sixty-fifth birthday. You might want to start now.

Excerpted from Keep It Moving: Lessons for the Rest of Your Life by Twyla Tharp. Copyright © 2019 by Twyla Tharp. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

This segment aired on October 29, 2019.