Advertisement

'Making Our Way Home' Illustrates History Of African American Great Migration

During the early 20th century, millions of black Americans migrated from southern states and moved to places throughout the nation in search of a better life.

It was a stunning shift for our country. For over six decades, this massive migration, known as the Great Migration, shaped the economic, demographic and cultural landscape of the U.S. as we know it today.

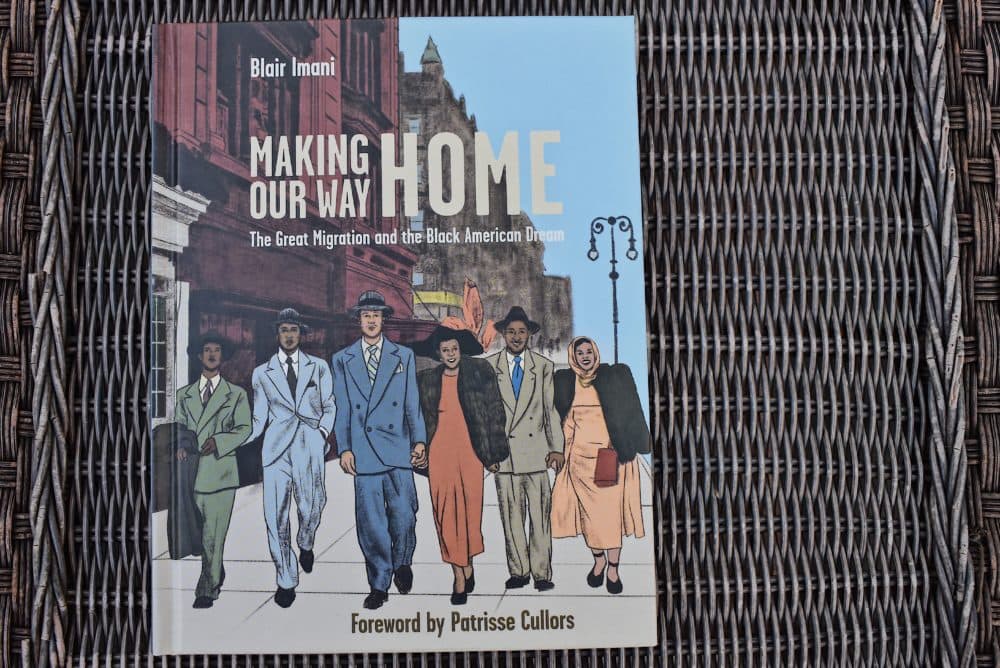

Author Blair Imani, a bisexual, black Muslim woman, chronicles this moment in history in her new illustrated history book, "Making Our Way Home: The Great Migration and the Black American Dream."

With illustrations by Rachelle Baker, the book reads like a graphic novel to point out “how privilege shows up in the way that we even depict black stories,” Imani says.

“I talk about colorism throughout the book and talk about things like passing for white, etc.,” she says. “I wanted to show a wide array of black folks who are brown skinned, who come from different backgrounds, and not just celebrities either, but everyday black people.”

The depiction of a variety of black stories starts right on the cover of the book, Imani says. The illustration on the cover shows Imani’s Uncle Lester, who was a gay man who came out later in the life. Next to her Uncle Lester is a drawing of the partner he could have had if he were able to live his life openly. Alongside of them is Imani’s great aunt and great uncle, and then Imani and her partner.

“I just loved the idea of people picking up this book because they love black history, but then also realizing that they have a gay couple on the front of this book,” she says. “And it shows that we are a diverse and multifaceted people, and all of our stories matter.”

Interview Highlights

On her intention in writing this book

“I didn't have black history really robust in my schools. I had kind of like home teaching in terms of black history where my parents would kind of complement whatever I was learning in school. And I've seen my younger cousins' history books and they're more robust in terms of representation, but how honest are they? And I think that's really the thing to interrogate. And so I have a glossary in the back of the book, so that way everything is kind of laid out in a way that's approachable again, and it's written [at] about a fifth or sixth grade level, which is what most Americans reading level is at. And so that being said, I just wanted to make sure it was accessible.”

On the incomplete history of African Americans between the post-Civil War period to the 1950s

“Just the fact that so much happened and so little is written. I remember being in an American history course, even in college, and we did our chapter on the 1920s and there was no mention on the Harlem Renaissance. And so like I was looking at the syllabus, and I was like, 'Clearly I've missed something like there's no way that the teacher omitted this. Maybe there was like a class that I missed or something.' And I went to the teacher and he was like, 'Oh, I guess that's important.' And I was like, 'I guess?' You know, like you're teaching ... in a predominantly black neighborhood, Baton Rouge is a majority black city, and yet the attendance at Louisiana State University where I attended was about 12%. So clearly there's a gap, and it's showing up in the curriculum.

“And also the fact that as I was doing the research for this book, I'm realizing that, 'Hey, if 40% of farmworkers at this time period during the Great Depression were black people, why are all the stories that we hear, like 'Grapes of Wrath,' you know, dustbowl, different documentaries, why are they only focusing on these white folks?' So it was just kind of those things, where it's like, OK, I thought I was aware of all the gaps, but there's even more.”

Advertisement

On her own family’s story of migrating from the South

“So I remember one night when I had brought over all my American Girl dolls to my grandmother's house, and she was looking at the story of Addy, who was one of the, I think, only black American dolls that they [had] in that series … when I was younger. And so I was telling her about Addy's story, and then she starts telling me about her own, which happened in around the 1930s. She was born in 1929. And she starts telling me about how my great grandfather had to collect all of his belongings and flee because there was a lynching in their city in Little Rock, Arkansas. And the Klan had basically lynching as a form of mass intimidation. And in this particular case, the Klan said, 'And if any [slur] goes to work tomorrow, you'll be dead just like this one.' And my great grandfather — and everyone says I'm so much like him — he decides to go to work the next day because he's not going to be intimidated. He has a family to provide for. So he goes into work. The owner of the store where my great grandfather works, he gets word that my great grandfather is going to be killed, and he doesn't want to see that happen. He was a white man and he gave Big Daddy his car and he said, 'Get out of here. Like go, just go.'

“And it wasn't like you could just pick up and leave, you know? He had a family. And it was this big moment of does he leave or does he stay and does he die? And that could be the end of the story right there. But he picks up and he leaves, and it was really kind of a community coming together, people cooking and making sure that his car was full of food, making sure that his family would be taken care of because they had to get out of that house regardless of whether or not my great grandmother or my grandma could go with him. So they basically evacuated, spread the family out. And that's why we live in Pasadena, because he came out to Pasadena. And so it's really difficult to talk about, but I wanted to open the book with that story because it's why I'm here — and that's profound.”

On how she chose the stories in the book to balance ‘the beautiful and the ugly’

“The 1920s really exemplifies this and was a great starting place for me because there's a lot of research and a lot of chronicling of what happened during the Harlem Renaissance, but it often omits LGBTQ contributions. So I was like, 'OK, well, it's time to queer the Harlem Renaissance,' and really talk about how the first magazine that was created by black and LGBTQ people and folks of those intersections was called 'Fire' and it was created in 1926.

“I talk about how it was like this point at which it was crucial for black folks to cast off every element that white society had thrust upon us, including heteronormativity and gender expectations. And I wanted to lift that up. But then also, it was a time where lynching and violence was really peaking — the nadir of American history in terms of race relations. So 'Beautiful and Ugly, Too' speaks to that, but there's so much beauty happening in the 1920s in particular, but so much ugliness. And then throughout the book, it was really difficult to kind of zero in on moments that were crucial.

“But I also, going to distribution of privilege, I wanted to talk about how Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte were contemporaries, for example, but because of colorism, Harry Belafonte was imbued with more desirability. And so instead of depicting him in the book, I decided to depict Sidney Poitier and also uplift how 'Ebony' was kind of one of the few magazines that were depicting people and how even though these movies were happening in black and white, Dorothy Dandridge was lifted up higher than some of her darker hued sisters, and how Lena Horne even spoke to this. So I thought of how I could add to existing conversations that folks are more in touch with in terms of black pop culture, and look at how I could contribute [to] that space by deconstructing it, by looking at it from an LGBTQ lens, from a privileged lens, looking at it from classism and colorism and dive into that.”

On why it was important to her to tell stories about the history of the black LGBTQ community

“Myself, I'm a bisexual, black Muslim woman, and, you know, I have some skin in the game, clearly, but I think too it's important to show other folks. I remember explaining to my parents why the bathroom bill in North Carolina mattered to them and how bathrooms were segregated by race and they are now segregated by gender, and how social categorization is harmful to everyone. And so it really became important to me not only to include, but also to elevate. [Texas Rep. Barbara Jordan] was a lesbian. That's important because there's such a conversation now that says, 'Oh, this is a new phenomenon. Oh, this has come out of nowhere. This is novel. It's a trend.' That's what I hear often from older folks is that it's a trend, but it's not. It's part of black history. It's part of American history.”

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Peter O'Dowd. Samantha Raphelson adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on January 15, 2020.