Advertisement

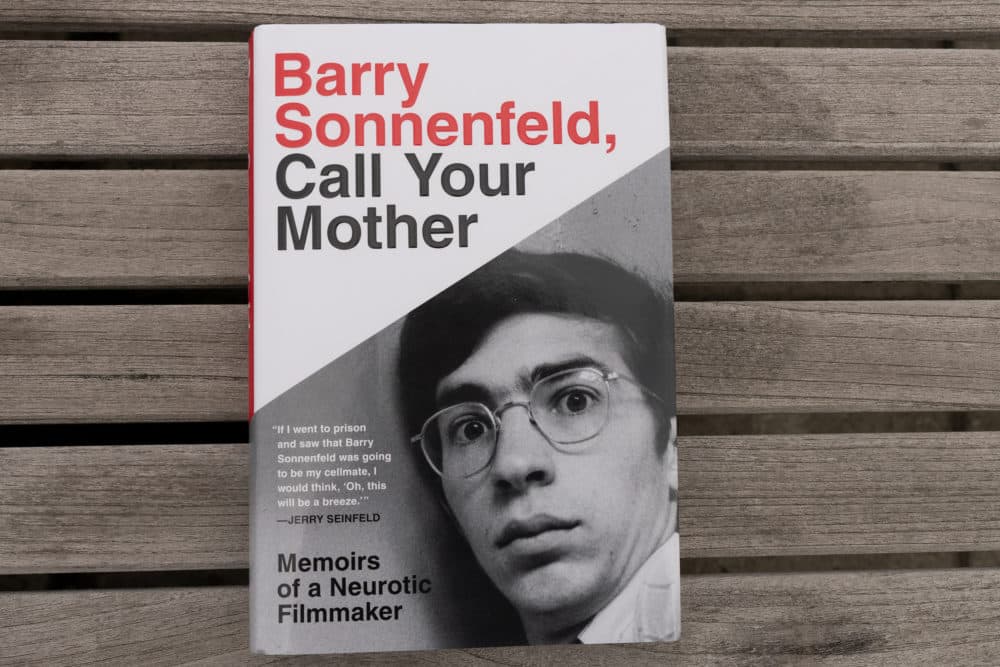

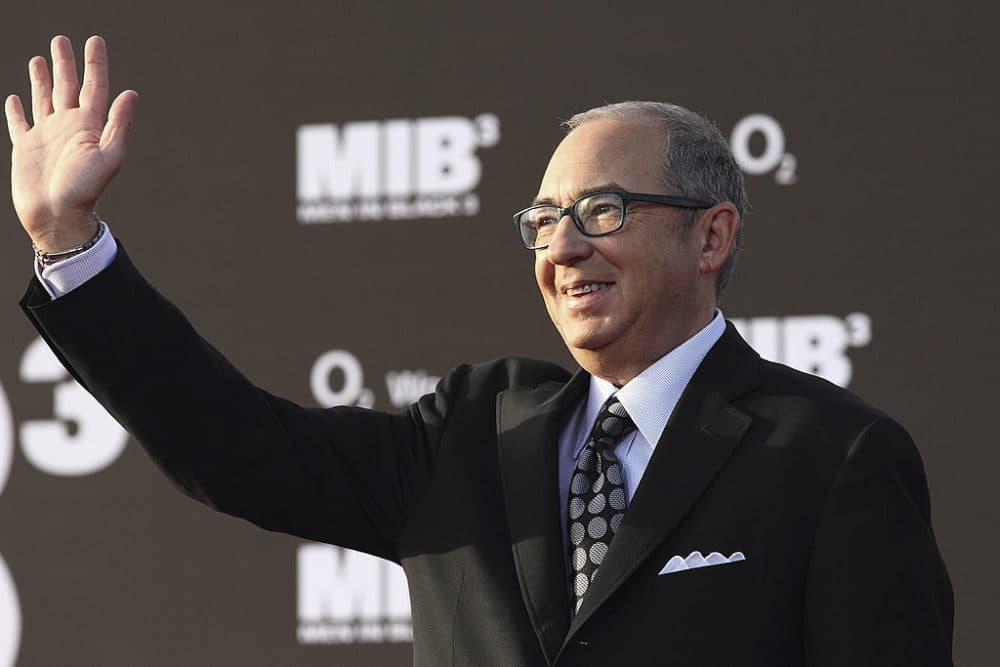

'Men In Black' And 'Addams Family' Filmmaker Barry Sonnenfeld Pens New Memoir

Editor's Note: In the audio, Sonnefeld discusses being molested by a cousin as a child. Though he does not go into detail, the word "penis" is used.

The story behind the title of filmmaker and writer Barry Sonnenfeld’s new memoir — "Barry Sonnenfeld, Call Your Mother" — could have come straight out of a movie.

At age 17, while waiting for Jimi Hendrix to take the stage at the Winter Festival for Peace at Madison Square Garden, he says he heard his name over the PA system.

“Barry Sonnenfeld, call your mother,” the PA system announced to the massive crowd.

He says he stood up immediately, exposing himself — and that’s when the “Barry” chants began.

What he originally thought was some family emergency was really just his mom wondering where he was. It was 20 minutes past his curfew, he says.

Sonnenfeld’s autobiography is laced with funny, sometimes absurd, moments from his childhood into adult life. Woven throughout are reflections on more serious times, such as when he writes he was molested by his cousin, whom he had nicknamed “Cousin Mike the Child Molester,” or “CM the CM” for short. He claims his parents allowed the molestation to occur under their roof.

The 66-year-old writes in his memoir that he’s one of the most neurotic people on the planet. It’s a quality he takes pride in, he says, and it’s helped fuel his successful career in film.

“I feel that it has given me a quirky attitude toward life and toward movies. The movies I tend to do — ‘Addams Family,’ the ‘Men in Black’ movies — are all about light-hearted dark issues. And so that's been my sort of viewpoint on life,” he says. “Things are dark, but let's sort of have fun.”

Advertisement

Interview Highlights

On his mother’s strange behavior

“I became a senior in high school and prepared to go to college. [My mom] called it sleep-away school and said that if I went away to college, sleep-away school, she would commit suicide. So I spent three years living at home. And then when I was gonna be a senior, I realized, wait, I can go away to another college and my mother commits suicide? Two birds, one stone. But she totally reneged on the offer. But I did spend my senior year at Hampshire College.”

On being molested as a child

“Eventually I confronted my father when he was in his 90s. I went up to the Upper West Side and sat with him and I said, ‘Why did you let CM the CM live with us?’ And my father had three really interesting reasons. One, he said, don't forget, child molestation didn't have the same stigma back then that it has now. To remember, your mother was very sad because of all the affairs I was having so I thought she'd be happy having Mike around because he would drive her to the Paramus Park Mall and stuff. And the third reason, ultimately was where my brain went tilt and I had to leave, which was when he said, besides, I never thought Mike was molesting you. I only thought he was playing with your penis. So that's when you go tilt and you say, well, thanks dad, see ya.

“I don't want to make light of this or my parents’ decision to let this happen, but I will say, I'm here with you now talking about a book, and I've had a successful life with a great wife and children. So, you know, I can't get too morose about it.

On embracing the neurotic

“I'm very proud of that. In fact, both Larry David and I both worked with Cheryl Hines, who's a great actress. And we each wanted Cheryl to tell us that we were the most neurotic. And Cheryl didn't want to tell us because she knew whoever wasn't the most neurotic would be insulted. And she was on the David Letterman show a night, and she announced that I was the most neurotic person she’d ever met. So years later, I was at a power breakfast place in Manhattan, and from across the room, I hear Larry David's voice screaming, ‘Sonnenfeld, you claim you’re more neurotic than me, but you're eating eggs with yolks. You're putting butter on your bread and you're eating bacon.’ And I yelled out, ‘Extra crispy!’ So I won that one.”

On accidentally getting into the film industry

“I went to [New York University] graduate film school literally only because it kept me out of the job market for three additional years. I had no interest in film. I wanted to be a still photographer, but didn't want to be alone so much. And so at film school, I realized I kind of was good at cinematography. And when I got out of school, I felt that if I owned a camera, I could call myself a cameraman without being a dilettante. And one night I was at a party where everyone was from Darien, Connecticut, except one other Jewish guy across the room. We started to talk. It was Joel Coen of the Coen brothers. Joel and Ethan had just written the script for their first movie, ‘Blood Simple,’ and we're going to shoot a trailer and use that trailer to raise the $750,000 to make the movie. So I said, ‘I own a camera.’ And he said, ‘You're hired.’ So we shot the trailer. We got along really well. I helped them raise the money. It took a year. And the first day on the set of ‘Blood Simple’ was the first day that Joel, Ethan or I had ever been on a movie set.”

On how he became the director for the first “Addams Family” movie

“I was in L.A. and my wife and I were in bed watching the Indianapolis 500, of all things, and the front desk called up and said, Scott Rudin, who's a famous movie producer, has left a script for you. He wants you to meet him in two hours at Hugo’s, which is a local LA hangout. So I read the script and of all the scripts be sent to me, it was kind of the perfect one because Charles Addams, A) is a very dark visual cartoonist, B) I grew up with his cartoons and I loved them. I didn't like the script. I went to Scott, I went to Hugo’s and said, ‘Why me?’ And he told me that he had gone to Tim Burton and Terry Gilliam. They had both passed. And he said, ‘Since all the good directors passed, I thought I'd offer to you.’ ”

On the relationship with his wife, Susan, who he calls “Sweetie”

“Well, I have to say, that's an incredibly good question because Sweetie was very nervous to marry me. And the reason was because she thought I had no good role models and she was concerned that I would have no idea how to be a good, loving husband. But I proved her wrong. And she's still Sweetie and we've been married for 31 years and very, very happy.”

On being a parent

“The challenge of being a parent is not to be like what your parents were. Yet you become what your parents were. I became my mother and my father. I'm like my father, who is a salesman and, you know, I'm always telling people what to do. And I have my mother's fears and worries. When my daughter flies, I'll stay up all night looking at FlightAware and go, ‘Wow, why did her plane just go from 34,000 feet to 33,900 [feet]? What's going on?’ ”

On being in a plane crash

“The story sounds so unbelievable that I actually, at the end of the chapter, publish the [National Transportation Safety Board]’s transcript of the black box where you hear the copilot say things like, 'Yee ha' and 'I don't think we're going to make it.' ”

On his biggest piece of advice to aspiring filmmakers

“You know, at the end of the book, I mentioned that Will Smith wanted to take me to underprivileged schools in Philly where he grew up, and say, if this guy can direct big-budget movies with movie stars, anyone can. And I think that would be my piece of advice, which is that if I can do it, anyone can. And figure out what you want to do in life that will give you joy and you will somehow find a way to make a living doing it.”

Book Excerpt: 'Barry Sonnenfeld, Call Your Mother'

By Barry Sonnenfeld

A very public display of my overwhelming fear of Sweetie’s death happened on the set of Wild Wild West, and it involved Will Smith. Sweetie had been feeling occasionally dizzy for a few days, and I finally nagged her into going to Dr. Koblin, our LA doctor— and somehow this makes sense in Hollywood—a former business partner with Wolfgang Puck in the frozen food industry.

That night we were filming at Lake Piru, about an hour and a half north of Los Angeles. The scene included four hundred Civil War reenactors—all on the Confederate side. These reenactors are the real deal. I got a sense that if we told them we needed to bring back slavery to make the scene more realistic, they would have whooped and hollered.

Sweetie had just gotten back from Koblin as I was leaving our rental house for the set.

“How did it go?”

Well, you know Koblin. He couldn’t find anything wrong, so he’s sending me to get a brain scan tomorrow just to make sure.”

“What?”

"Barry. I’m fine. Go do your job. Have fun. I’ll see you in the morning.”

Filming a scene with Civil War reenactors is always hard because they’re sticklers for reality.

“We wouldn’t stand like that.”

“We wouldn’t run; we’d march.”

“I should say that line, not him. I’m a lieutenant.”

The reenactors were driving me crazy with their regulations

and negativity and, um, fellas, just in case you didn’t know . . . Wild Wild West is a movie with a made-up story that has an eighty-foot mechanical spider in it. Relax.

The areas surrounding LA are always cold at night. Often frigid. This was one of those nights. We had a Civil War tank that had to start submerged in the lake and drive out onto the land. The mechanical effects kept breaking down. The lighting was taking too long. I’m frustrated and cold. I’m worried we’re not going to get our work done and we’re scheduled at the Lake Piru location for only one night.

At around midnight, which means we’re close to our lunch break, I start to think about Sweetie and her brain scan, and I realize she is going to die.

No one gets dizzy for no reason. I collapse on the ground and start to weep. I’m howling and shivering like an injured animal.

Will rushes up to me,

“Baz. What’s wrong?”

“Sweetie’s dying.”

“What?!”

“Sweetie’s dying.”

“What are you talking about?”

“She has brain cancer."

Will looks at my sobbing face and collapses on the ground next

to me. He grabs me and hugs me like Sweetie’s life depended on it.

“If anything were to ever happen to Jada. Oh, poor Baz. Poor Sweetie. I am so sorry, Baz,” Will wailed.

The producers Jon Peters and Graham Place signal for a John Deere ATV with a flatbed. They load Will and me onto the back of the vehicle as we’re holding onto each other in a death grip, yowling like dying beasts.

We are, of course, John Deere’d past 400 Confederate reenactors, each and everyone staring at the sobbing, hugging Jew and Negro.

It took about five minutes to get to base camp—Will and me blubbering our way up the dirt road where the caterer, trailers for makeup, grip, electric, and all the personal campers are set up in a circle. We pull to a stop. Will looks at me, his eyes red from crying. Both of our shirts are soaked from each other’s tears. I see the pain he’s feeling for me and Sweetie.

And I say:

“Maybe I’m just hungry.”

“What, Baz?” Will says gently.

“Maybe I’m just hungry. Sometimes that makes me emotional. Or dizzy.”

Less gently: “What, Baz?”

“Maybe Sweetie is okay.”

“She has a brain tumor. How is that okay?”

“Well, we don’t know that for a fact. At the moment it’s just that

she’s a bit dizzy.”

Will looks at me and realizes that he should have known better.

Suspiciously, he says,

“So, what’s with the brain cancer?”

“Well, the doctor couldn’t find anything wrong with Sweetie,

so he’s doing a brain scan tomorrow. She’s probably fine. I’m going to get some food. You want anything?” I say as I walk toward the catering truck.

“Baz. I was just bawling like a baby in front of four hundred Confederate troops because you were hungry?”

“I guess.”

Five minutes later I’m pounding on Will’s door.

“Will. Come quick. Graham’s dying!”

“I’m not fallin’ for that, Baz.”

“No, seriously. He’s got a piece of cauliflower stuck in his throat.

He’s making horrible sounds and he’s blue. Ya gotta come.”

He better be dying, Baz,” Will says as he opens his camper

door.

We race across base camp to my trailer, where Graham is bent

over, looking very blue.

“Will,” I scream, “do you know the Heimlich maneuver?”

Will shakes his head. But he knows he needs to do something

fast. He grabs Graham by the legs and holds him upside down, newborn baby style. He then starts to swing Graham like a pendulum, each time on the down swing crashing Graham’s back against the camper’s fridge. After five brutal swings, Graham, as if in a Warner Bros. cartoon, coughs out a rosette of cauliflower.

Will places Graham on the floor. “White folk.”

Then he walks out of my camper.

Excerpted from BARRY SONNENFELD CALL YOUR MOTHER: Memoirs of a Neurotic Filmmaker by Barry Sonnenfeld. Copyright © 2020. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Todd Mundt. Serena McMahon adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on March 11, 2020.