Advertisement

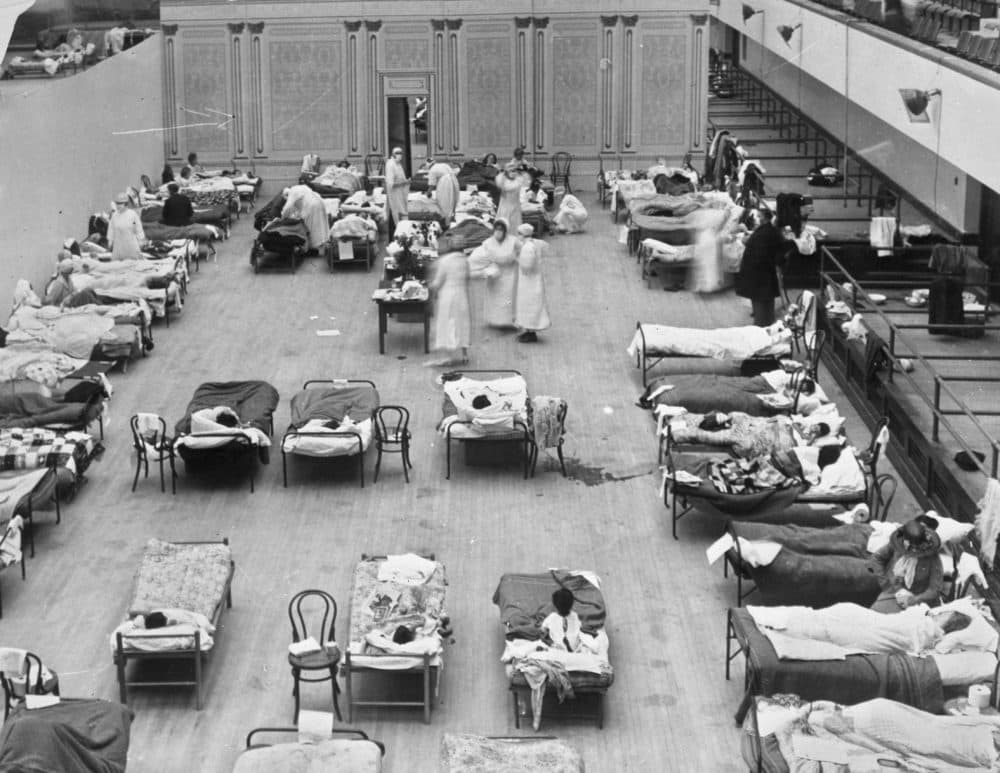

Coronavirus Mask Debate Echoes Messaging From 1918 Flu Pandemic

Despite research out of Wuhan this week that the coronavirus can linger in the air, Vice President Mike Pence opted to not wear a mask during a visit to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota on Tuesday.

In images circulating on social media, Pence's bare face stands out in a crowd of masked health care workers and patients. Pence chose to ignore clinic rules because, as he says, he wanted to look health care workers in the eye when he thanked them.

Defying mask orders isn’t new. During the flu pandemic of 1918, what people often refer to as the Spanish Flu, a protest group formed and called themselves the Anti-Mask League.

The flu pandemic of 1918 was much deadlier than the coronavirus pandemic has been so far. Historian J. Alex Navarro of the University of Michigan's Center for the History of Medicine says the orders issued in 1918 were not as sweeping as recent stay-at-home orders, but there were closures of non-essential business, schools, theaters and churches. Public outdoor gatherings, and sometimes even indoor gatherings, had bans as well, he explains.

Although it’s hard to judge whether or not people were compliant with the orders more than a century ago, it seems most people were cooperative based on newspaper reports.

But one city, in particular, is notable for its public distaste for masking orders during the flu pandemic of 1918. Many San Francisco residents “balked at some of these social distancing orders or these non-pharmaceutical interventions.”

“There were two mandatory mask orders in San Francisco. There was one that came in late October on the heels of some of the other social distancing measures,” he says.

The first order was met with “fairly widespread compliance,” he says. The government did their best to tie it with being patriotic, considering World War I was underway.

After seeing some decline in influenza cases, mask orders were lifted in San Francisco. But soon enough, in December of 1918, “influenza came back and they had another spike of cases,” he says.

By then, San Franciscans were fed up, he says. And in January of 1919, about a month into the second surge, the city decided to reimplement the masking order, which “people really detested,” he says.

Advertisement

“They didn't want to have to go through another set of any of these orders,” he says.

Masks at the time, crafted from gauze, were uncomfortable to wear, he says. Additionally, there were a lot of people who believed the order defied their civil liberties as Americans. Thus, the Anti-Mask League — which included prominent physicians — was formed, he says.

One Anti-Mask League meeting packed more than 2,000 people in an auditorium, Navarro says.

“None of them were wearing masks, of course, completely violating what we would consider social distancing today to protest these orders,” he says.

Even though the U.S. is very different than it was back during World War I, there are quite a few parallels, especially in the context of wearing masks. Up until a few weeks ago, medical professionals were debating whether masks were useful. Now, mouth and nose coverings are mandated to enter many public spaces in various areas of the country.

The same debate happened during the flu pandemic. While there were physicians who promoted the use of masks in 1918, Navarro says plenty of doctors also thought the coverings weren’t effective because “gauze masks were too porous to really trap any germs.”

Navarro says the key takeaway from San Francisco is not solely the role wearing a mask plays during a public health crisis. Successfully slowing the spread of a virus can happen when masks are worn in conjunction with abiding by other social distancing interventions, he says.

Just look to San Francisco in 1918 for the proof, he says. The city was slow to act and didn’t keep orders in place long enough.

“But most importantly,” he says, “they decided they were going to rely much more heavily on masks than on some of the other orders that would have been more effective.”

Cassady Rosenblum produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Tinku Ray. Serena McMahon also adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on April 29, 2020.