Advertisement

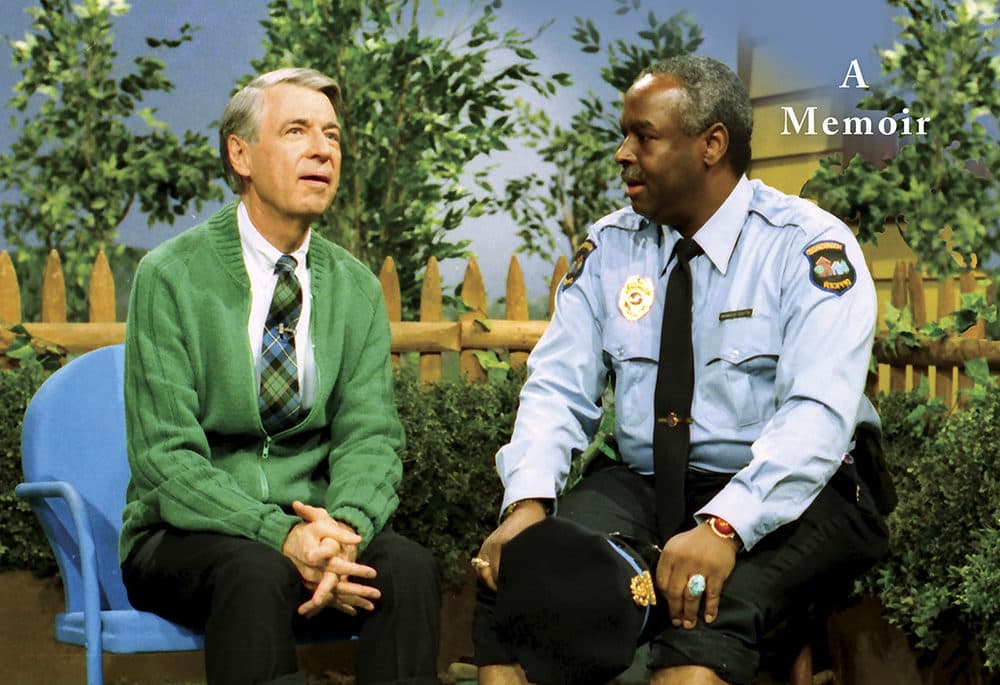

François Clemmons Reflects On Life Beyond 'Mister Rogers' Neighborhood'

François Clemmons overcame a difficult childhood and discrimination to become a musician, noted choir director and recurring character on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.”

His role as Officer Clemmons on the show was groundbreaking. He served as a positive image of a black American at a time when racial tensions in the U.S. were high.

And as he writes in his new memoir, he found a family in Fred Rogers, a friend and mentor, and along with Fred's wife, Joanne Rogers. He writes about his life and his deep friendship with Rogers in his new memoir "Officer Clemmons."

“I wanted people to understand the grit and the substance of how I got to be who I am. I didn't want them to misunderstand and think, ‘Fred Rogers discovered you.’ He did not,” Clemmons says. “I knew that I could sing, and I knew who I was before I met Mr. Rogers. However, I would never have had the kind of career, the rocket charge, had he not fallen in love with my voice.”

Singing with Rogers made everything “deeper and richer and more enjoyable,” Clemmons says.

“If he didn't like an arrangement, he might say, 'We need to change this word or that note,' ” Clemmons says. “But generally speaking, once I started singing, the roles were tremendously reversed. He was a fan and I was the star.”

Interview Highlights

On growing up in the segregated South with an abusive father and stepfather

“It was horrible. And I was wounded. I was walking around very, very unhappy for a long time before I was able to look at those situations without, you know, feeling nervous or getting sick. They were a nightmare. I had physical nightmares. ... I was so young. And to see all that blood, that blood. To this day, I can barely stand the sight of blood.

“As a matter of fact, I wasn't able to talk about it until I went into therapy, and Fred was the one who convinced me that I wasn't crazy. What he said to me, 'You are bleeding. That's why you are going through some of these issues that you talk about. And you need to go talk to someone professionally.' And I listened to him very carefully. I trusted him implicitly. So I went and got in touch with a psychiatrist at Columbia University who helped me to understand that I was just a boy, and my parents were not fighting and acting aggressively like that because of something I did.”

On how music became his refuge after his grandfather’s death

“When my parents were fighting and I was so lost, I sang the songs that my grandfather, I thought they were the songs that he had sung about his African ancestors, which were my ancestors. And he didn't live very long because there was a flood that came to that part of the country, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and I began to sing those songs when he was lost. I was grieving. That was the moment that I started singing out loud and in front of strangers, and that became my retreat. But people heard me and said, 'Oh, that sounds great. What are you singing?' And I told them, 'They're the words that my grandfather sang.’ ”

On early discrimination from his school guidance counselor who told him he should go to trade school instead of being a musician

“Another one of those open sores that I carry around, all my life people have underestimated me. That's how I verbalize it. And ... that counselor who was insistent that I go to this vocational school, I lost it in her office. And that was the moment that diva Clemmons was born because I stood up, and I don't want to say anything coarse on the air, but I was no longer a child with her because she was gonna take my dream. So I got backbone, and I told her she doesn't know who I am and that she had no right to talk to me that way and that I was gonna go to [Oberlin College and Conservatory] and become a famous singer, and there was nothing she could do about it.”

On Rogers advising him not to publicly discuss his sexual orientation

“That's only partially true. Yes. The other part of that is if I had chosen not to be on ‘Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,’ then I could do whatever I chose to do in my private life. That was a price to pay to be with him, and I thought it was too much to lose. I was determined to participate in this historic television program for children. This man who had a way of communicating and hypnotizing in a way his intensity, his sincerity, made people want to be with him and tell him things. And ... the short of the long story is that I began to learn the rich dividends that an audience pays when you are sincere and honest and open. And when I was not on ‘Mister Rogers Neighborhood,’ I put those effects into my work.”

On the famous scene where he and Rogers put their feet into a wading pool

“I thought [that moment] was kind of light. I was expecting something like maybe calling [Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.] up or calling the president up or saying, you know, this is amoral and some kind of curse on these people, and he didn't do that at all. He said, 'Come, come sit with me.' And he said, 'You can share my towel.' My God, those were powerful words. It was transformative to sit there with him, thinking to myself, 'Oh, something wonderful is happening here. This is not what it looks like. It's much bigger.'

“And many people, as I've traveled around the country, share with me what that particular moment meant to them, because he was telling them, 'You cannot be a racist.' And one guy or more than that, but one particularly I'll never forget, said to me, ‘When that program came on, we were actually discussing the fact that black people were inferior. And Mister Rogers cut right through it,’ he said. And he said essentially that scene ended that argument.”

On why he didn’t go to Fred Rogers’ funeral

“It wasn't really my decision. It was Fred's decision still. I was conducting a choral workshop here in Vermont for the whole state. Some 250 kids, I arranged a program, sent the music to their music teachers, and I was at home and there were two or three phone calls. And when I finally got up and answered the phone, it was Lady Aberlin saying, 'Fred is dying, and we think he's gonna be gone, friends. But you need to talk to Joanne. She has something to tell you.' So I called Joanne. And what she basically said to me was, 'You are not to come home for any of these funeral services here in Pittsburgh because Fred said you cannot disappoint all of those children.' So I just literally sat down crying because I was so conflicted, and I felt I had to do honor. I had to honor that directive from him.”

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Peter O'Dowd. Samantha Raphelson adapted it for the web.

Book Excerpt: 'Officer Clemmons: A Memoir'

By François Clemmons

This show was turning out to be a far bigger feather in my cap than I could have ever imagined. I didn’t want to tell anybody, but I had my sights set on The Metropolitan Opera, and I considered this just a minor stop along the way. But at least I had enough restraint to keep my thoughts and plans about branching out to myself. I didn’t want to foul things up. Especially, when I really hadn’t begun my solo career yet and I had no real idea of just how high Mr. Rogers Neighborhood would go!

Fred was his gracious, low-key self all through my growth period with him. I found him consistently encouraging and genuinely interested in what I was doing. I guess I could have taken my cue from the Lenten service which had touched him deeply. During one of our conversations he spoke of how unique he thought it was that I had created a special program for Good Friday that was like the Black Negro Spiritual version of the European lessons and carols. He wondered where I had gotten such an idea. After I explained to him how much I loved the music of Black Americans and felt that it was my anointment to sing these Spirituals, and indeed bring them to the world, he suggested that perhaps he’d mention it to a friend of his who was the pastor of another Presbyterian church. He asked if I’d be interested in doing such a program again. I jumped at the opportunity and we made plans to follow up when the time came.

Advertisement

Fred being Fred, he said nothing more until one day his pastor friend from Allentown, Pennsylvania, Bill Barker, called and asked about the special Easter service I had done at Fred’s church. Fred had indeed spoken to him. Bill really liked the idea and let me know he couldn’t wait to hear it. In no time all was arranged, and I wound up going out to Allentown to sing a program of American Negro Spirituals for Rev. Bill Barker and his congregation. I thanked God for Fred’s recommendation. I received several calls in this manner over the next years, and I always thanked Fred and tried to show my gratitude. He always refused any gift except a “thank you” and a hug.

[...]

As I got to know him, I was surprised to find out just how sensitive Fred was. Once he brought chicken soup over to my humble little apartment when I was sick with the flu. I was lying in bed agonizing over the fact that I was missing out on important, pivotal rehearsals, when my doorbell rang. I dragged myself to the door, only to find that it was my new friend standing there with a brown bag. He greeted me warmly and asked if he could come in. He said that he had heard I was sick and had brought me some chicken soup to help me get well. I was touched because he hardly knew me—I was 24 and had never had the experience of being cared for by a man, let alone a white man. At first, I was a bit hesitant. Through this loving gesture and for the next few months, I would keep a watchful eye on him. I did not want to be caught unawares and get let down hard; I needed to see disappointment coming so I could protect myself. My experience up until that point was that some white people would never fully commit themselves to helping black people, while others would. I needed to know which kind Fred was.

Nevertheless, I began to trust him and stop by the station just to be around him and feel his warmth and approval. His door was always open to me, literally and figuratively. Soon we were discussing how I’d fit into a permanent role on the show. That’s when Officer Clemmons was introduced, and he and I discussed it. We talked about how I viewed the policeman in the Black ghetto and how young children should be able to turn to them for help in a crisis. Several of the other cast members were brought into the discussion—Mr. McFeely and Mrs. Frog and Reverend Bob Barker. I felt overwhelmed. I had no idea what I was getting into.

In my opinion, playing a police officer for a children’s television program meant more than just putting on a uniform. From my earliest years, my relationship with uniformed policemen had been a complicated one, and I knew that they were not the best friends for a black American boy. All during junior high and high school, I had heard graphic stories of my black peers having traumatizing run-ins with uniformed policemen. These encounters almost never turned out positively, whether they were in the right or wrong.

As I shared these experiences with Fred, I wanted to make sure that he understood the difficulty of portraying a role of this seriousness all the time. It was like walking a tightrope without a safety net. It brought with it a burden that he, as an entitled white person, might not fully appreciate. Even though I was willing to take on the initial challenge, perhaps it would be even more important that I have other roles that I could portray from time to time to relieve the stress and tension inherent in the historical relationship of the policeman to the black community. A steady diet of acting as a police officer would present a monumental challenge for someone of my nature and background.

Excerpt from 'Officer Clemmons: A Memoir' by François Clemmons. Copyright © 2019 by Dr. François Clemmons, from Officer Clemmons. Excerpted by permission of Catapult.

This segment aired on May 5, 2020.