Advertisement

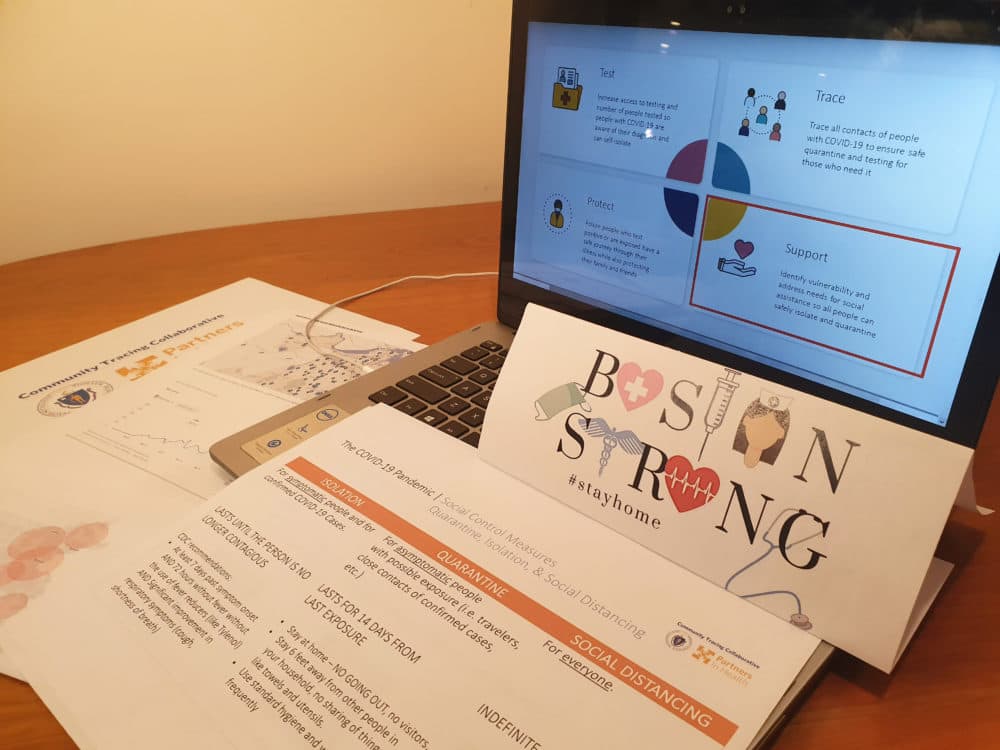

A Day In The Life Of A Coronavirus Contact Tracer

Resume

Some countries with the most success flattening their coronavirus curves used contact tracing.

It’s when officials trace backward from people who have tested positive for COVID-19 to find people they may have come into contact with, so those people can be treated or quarantined. This method helped contain AIDS and Ebola, but the challenge with the coronavirus is that it is airborne.

In places such as South Korea, contact tracers are using cellphones and credit cards to show where a person might have been. Apps are also being developed that use Bluetooth or GPS data to map a person’s movements.

But the telephone is still an important tool for contact tracers like Oscar Baez.

Baez was working as a foreign service officer in Jerusalem when the State Department called him home in March because of the coronavirus. Now he serves the neighborhoods of Boston, where he grew up, working as a contact tracer with Partners In Health.

“Social distancing measures, stay-at-home orders are our first line of defense against the virus,” Baez says. “This is the other tack of playing offense.”

Baez’s job consists of contacting any person who has been newly diagnosed with COVID-19 to inform them that they need to safely isolate, he says. Then, he calls anyone who may have been exposed to that person in the past 48 hours, even if it was before the person who tested positive showed symptoms.

He also follows up with the isolated sick person to ensure they can safely remain quarantined for two weeks, he says.

“We see the headlines of the virus being deadly itself, but for the most at risk and vulnerable in our communities, quarantine itself can be a life or death matter if you are unable to access food the next day, if you have a baby that needs formula and you've been unemployed,” Baez says. “And so I think it's really critical [for] us to maintain that human connection.”

Contact tracing is vulnerable to fraud and abuse, which is why Baez says his group uses caller ID that identifies their calls as the Massachusetts COVID-19 team. It’s important to build trust with the people he calls because “there’s already a huge sense of anxiety throughout our society based on what's happening,” he says.

Many people who tested positive also feel embarrassed or guilty to share information with Baez about where they went when they were infected with the coronavirus, he says.

“We have to reiterate that actually we have to maintain confidentiality,” he says. “But at the same time, when we inform those who have potentially been exposed, then they're the ones who sometimes want more information on who specifically was it that exposed this to me, and we can't share that.”

Baez says working in the immigrant communities of Boston where he grew up is helpful in his work because he understands “the inequalities that existed before COVID” that might put residents at greater risk.

Most of the cases he’s seen are nurses or other caregivers, he says. One woman told him that everyone on her floor of the assisted living facility where she worked contracted the coronavirus.

“[She] was too sick to really even describe these things, so I had to navigate through the process with her daughter, who was isolated in the same home, but also with COVID,” Baez says. “And … everything snowballs together.”

In a way, Baez is simultaneously playing the role of detective and counselor. He says families appreciate having someone on the outside walk them through the process.

“I think because of the digital divide, because of the existing inequalities in our systems, in our communities,” he says, “there needs to be somebody to accompany these patients.”

Cassady Rosenblum produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Tinku Ray. Samantha Raphelson adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on May 6, 2020.