Advertisement

Not Just Some History

Subscribe to the Kind World podcast here - and send us a message to share your story of kindness.

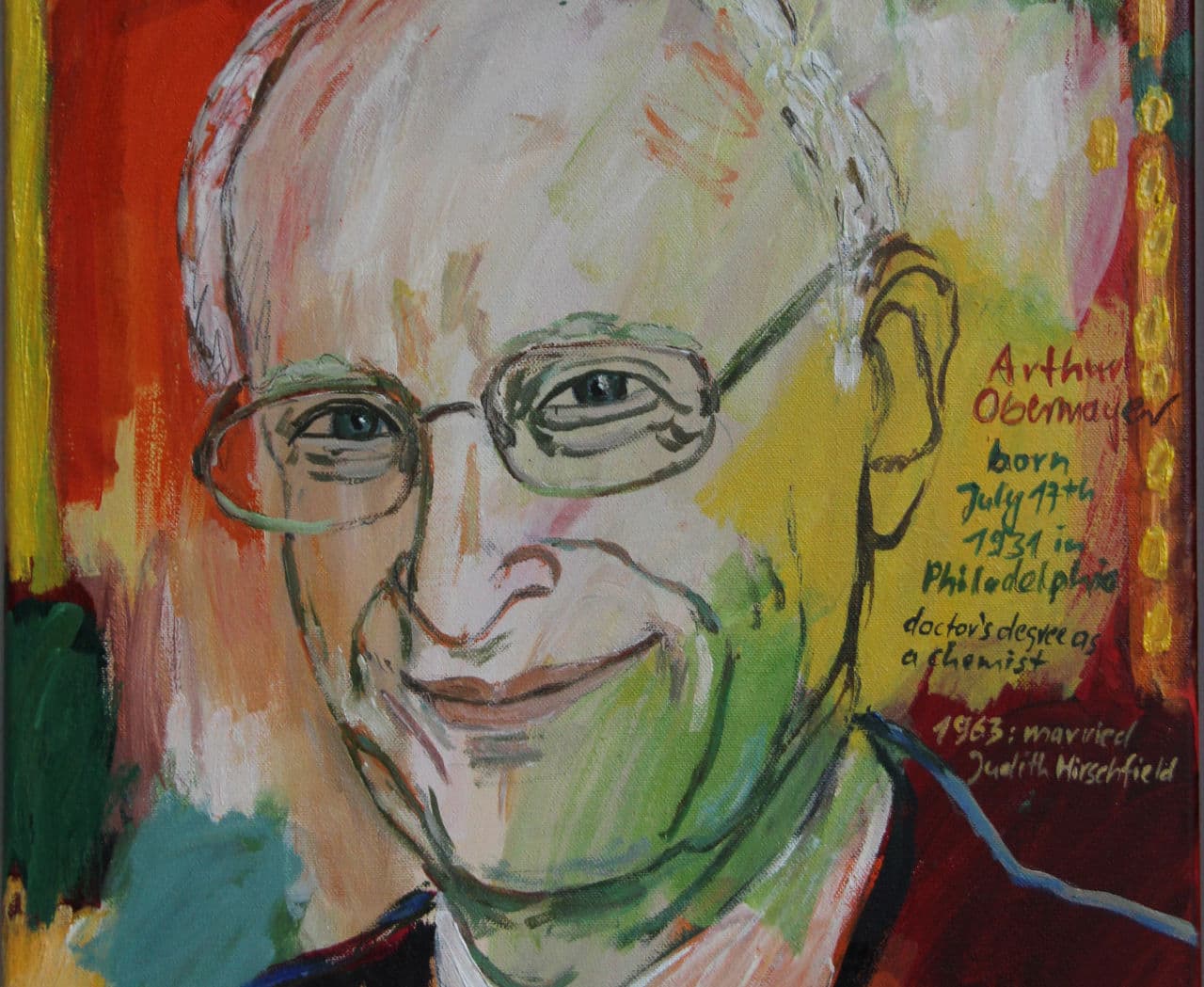

Joel Obermayer, of Arlington, has recently come to see his father in new light — and he learned that one of his father's projects helped connect a web of people all over the world.

Listen above (or read the transcript below).

JOEL OBERMAYER: You can know somebody for a really long time, like they’re your parent, right? My father is my father. There are certain things that I know know about him and that are part of the landscape that I just expect. I guess every now and then you get a chance to understand something in a completely different way. It just can shift your view.

ARTHUR OBERMAYER: My wife and I took a genealogical trip through Europe. We’re both Jewish. And every community we visited in Germany, there were people, volunteers, who had done a huge amount of work to preserve Jewish things. People who just felt it was the right thing to do. I decided something should be done, and I really felt that the best way to do it was to provide an award.

JOEL: He thought there really ought to be something here to recognize the work of German non-Jews who are interested in how people lived and what their culture was like. So it’s called the Obermayer German Jewish History Award. It’s awarded once a year in Berlin on Holocaust Memorial Day. It was just his project, and it was only more recently that we began to think of it as something else. And that really was after my father got sick.

ARTHUR: It was identified last January. Metastatic prostate cancer.

JOEL: It was all over his body.

ARTHUR: It started at really a very advanced stage.

Advertisement

JOEL: So we had this discussion — is there something we could do he could look forward to? And it seemed to be around this project that he’d been doing in Berlin. My siblings and I and some other people who worked with him, we kind of hatched this little plan. What if we contact the awardees, and just say, "Hey, what have you been up to since you won the award?"

And we wrote up this letter. I slipped in something that said, "He’s not in great health. If you have a personal message you want to send him, please send that too." A couple of them really stuck out to me.

So one example was this guy named Klaus-Dieter Ehmke, who had stumbled into an old Jewish cemetery that was in a state of disrepair, and he was interested in figuring out — the missing gravestones, where were they?

He heard about this little town. When he went there he started noticing, on flagstone paths and stairways, he’d see a stone with Hebrew writing on it. And he pretty quickly knew that those were gravestones.

He started like this charm offensive. He’d have Schnapps with them, and "Oh, by the way, there’s this stone over there. If I got you something better could I have it?" A lot of the time he would convince them that it was their idea to begin with. And then he’d come back by with a wheelbarrow and put it back as part of the cemetery.

I began to think, "Oh, this isn’t just like some history that's being saved. There’s actually kind of like a little movement going on." Especially now that they’ve been recognized and a lot of them know each other.

There’s like a web of people who have been impacted by these awardees. They're people who are trying to understand more where their family came from or who they are.

DEBBIE HURWITZ: Dear Obermayer German Jewish History Awards, she brought pictures of my mother that I had not previously seen.

DENNIS ARON: Dear Arthur, finding contacts in Germany to help with family research can be daunting. I was fortunate to be introduced to Hans-Peter, who preserves the memory of the Jewish communities of Nordhessen. I had thanked Hans-Peter Klein profusely for his efforts and many selfless kindnesses, but I never felt able to thank him enough.

JOEL: I only know a tiny slice of the people who have been impacted by this.

My father has kind of a scientific personality, and we certainly never talked about our emotions very well with him. I kept looking for the right moment to talk with him about it, and then I realized there was no right moment. So in a phone conversation that was planned about something else, I told him that we had gathered these letters, and all of his kids thought this was important to keep going, and that we were proud of him. And my father stopped and cried. We had to stop the call, to let him compose himself, and I called him back and he was still crying.

It seemed more and more likely that he wasn’t going to be alive for the next awards ceremony. He said to several people, "If I can’t be productive, I don’t want to be here."

ARTHUR: Joel’s enthusiasm has definitely re-energized me. I never expected that from him, and it’s made me feel so different about my life.

JOEL: We don’t how to keep this thing going that my father’s been doing, but my siblings and I are trying to figure it out.

ARTHUR: When I’m gone, to some extent, they’re prepared to take over for me. And there’s nothing that could make me feel better.

JOEL: Here's what’s really amazing to me: I think it’s making him live longer.

ARTHUR: A few weeks ago, I was prepared for my end. Now I don’t feel that way. I may die tomorrow, but at least I’m working to be doing something that is meaningful.

CHRISTIAN REPKEWITZ: For me, the research of the life and fate of former Jewish citizens of my hometown, Altenburg, always was a task I'd liked and still do. But to be nominated by people from foreign countries, and to get an award for the work, gives the work some new meaning, especially emotional.

CHRISTA NICLASEN: If the work is honored, you think you have to do more. You don't just sit back and say, "Oh, how nice." You say, "What else can I do?"

An update: We are sad to report that Arthur Obermayer passed away on Jan. 10, 2016. He was 84.

We want to hear your stories. Send a message, find us on Facebook or Twitter, or email kindworld@wbur.org.

Kind World is a project of the WBUR iLab, sharing stories of the profound effect that one act can have on our lives. Listen on air, online or subscribe to the podcast.

This segment aired on December 24, 2015.