Advertisement

Kennedy Lived Tragedies, Political And Personal

ResumeThere wasn’t anybody too small or too insignificant to get his personal attention. He just has been a giant for the little people — he used to call them the people who lived on the second floor and the people that lived in the back streets. --Gerry Doherty

In the heavily Irish-American wards of Charlestown that Gerry Doherty represented in the ‘50s and ‘60s, the watchword was: Don't forget where you came from.

Of course, the kid he agreed to help came from money. The kid was rich and his brother was famous. And Gerry Doherty got recruited by that brother, the president of the United States, to run Ted Kennedy's campaign for the Senate. It was 1962. And John Kennedy's roommate from Harvard had been warming that Senate seat vacated by the president until Ted turned old enough at 30 to replace him.

“They sent me to do the debates,” Doherty recalled. “And, at that point, Teddy didn't appear to be ready for them.”

The debate was with Eddie McCormack, the state's attorney general and scion of a competing clan of Irish Americans whose chieftain was merely the speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. McCormack's motto was, "I Back Jack, But Teddy Ain't Ready."

Former Boston Mayor Ray Flynn was there at the debate.

“I supported Eddie McCormack and a lot of people like me felt that he deserved that seat because he had worked hard for it,” Flynn said.

One line would endure from that debate. It came at the end. McCormack threw high and inside with this dimissal of his opponent:

"I ask, since the question of names and families have been injected, if his name was Edward Moore — with your qualifications Teddy — if it was Edward Moore, your candidacy would be a joke."

“You know," Flynn said, "Eddie McCormack was right."

And it didn’t matter. Ted Kennedy became senator.

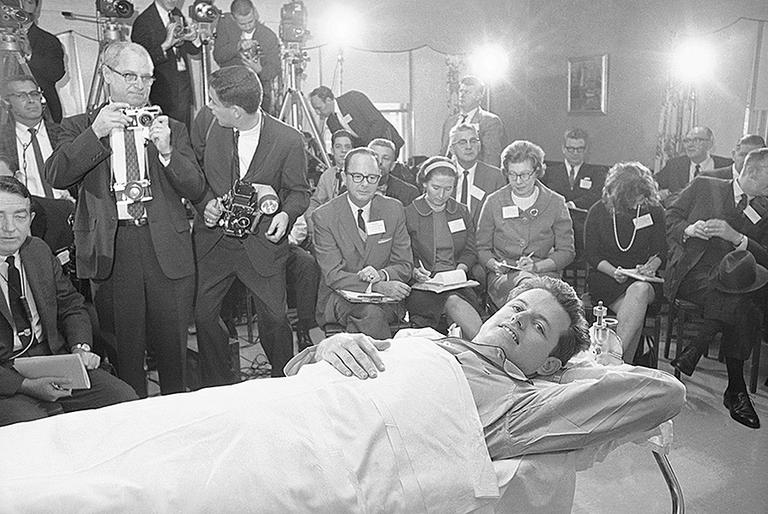

Life is unfair, Jack Kennedy once observed. He was murdered at 46, Robert at 42, and in between Ted nearly died in a plane crash that killed the pilot and an aide in 1964.

Gerry Doherty remembers that as Kennedy recovered from a broken back, he asked about Doherty’s own long hospitalization for tuberculosis.

“He became very interested in how the little person could go through these illnesses, which were so expensive,” Doherty said. “And I think that that was the beginning, the germ of his great commitment to health care.”

Former state attorney general and Lt. Gov. Frank Bellotti ran on the same red, white and blue Democratic ticket as Ted Kennedy in 1962.

“He’s one of the few people — I can't think of any others — who does exactly what he thinks is right without worrying about how it falls politically,” Bellotti said.

Nine terms in the Senate, the third-longest-serving senator in history, the Kennedy who was derided and taunted for his presumption in seeking the office, ended up accomplishing more than both his older brothers.

“He has been just a lion,” said Mardee Xiafaris, who joined the Kennedy camp in 1970 and has been a longtime Democratic National Committee member.

“The proof is in the measure of the man, and his values and his work ethic and his capacity — whether it's charm or wits or smarts or political savvy -- to simply put together coalitions of people and to leave landmark legislation, to be the king of the Senate in terms of commitment to healthcare issues, education issues, labor and workforce issues.”

Despite his ease in the Senate, Ted Kennedy's early career was rocky, his path more difficult than his brothers. In South Boston in the ‘70s, he was met with anger, taunts and tomatoes over his support for school desegregation and forced busing.

Ray Flynn, who represented South Boston before becoming mayor, faults the federal judge, Arthur Garrity, who imposed that busing plan — and Kennedy, too.

“Teddy had a big impact on Arthur Garrity,” Flynn said. “Arthur Garrity had no responsibility to talk to the parents, to the people, because he was a judge.

"But Teddy Kennedy more or less appointed him. Teddy Kennedy could have put the word in his ear to, you know, open this process up so people have an import -- particularly parents — and I think that was the failing of Boston during that period in time.

"It wasn’t that anybody was opposed to better schools or integration of schools in Boston, it was the way you went about it."

And yet, Gerry Doherty says, Kennedy did something extraordinary for his opponents.

“They had some litigation in the federal court, and one of the problems that they had is they had no money and they couldn't get their legal briefs printed," Doherty recalled. “He called me, and I called two people, and they came up with the money, and so the legal briefs were printed.”

So the opponents had their say in court. Yet nationally, as in South Boston, while the image of his dead brother shone, Ted’s was tarnished. Until his second marriage to Victoria Reggie, his middle years careened from substance to squalor, associated with two place names: Palm Beach and Chappaquiddick, where he drove off a bridge late one night and left the scene of an accident where his passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, drown.

Ultimately, her death and his actions helped close off his path to the presidency, which ended with an odd and unsuccessful insurgency against incumbent Jimmy Carter. At the convention in 1980, Kennedy delivered what might have been his greatest speech, on themes that still commanded his attention almost 30 years later.

“Programs may sometimes become obsolete,” Kennedy said then, “but the ideal of fairness always endures. Circumstances may change, but the work of compassion must continue. The poor may be out of political fashion, but they are not without human needs. The middle class may be angry, but they have not lost the dream that all Americans can advance together.”

Mardee Xiafaris says she still has that speech, framed.

"He sent it out to the delegates. Signed them. I still have it. I look at it passing through my study every day."

After that run, Kennedy gave up his quest to be president. Xiafaris says he was liberated from expectations of others pushing him in that direction.

Gerry Doherty says Kennedy then embarked on the legislative career as his mission in life.

“From that point on, I mean, he just was outstanding, he was stellar on almost every single piece of social legislation that’s gone forward in this country.”

Some of his bills that followed created family and medical leave, enabled employees to keep their health insurance after leaving their jobs, raised the minimum wage twice and increased the funding and quality of education. He embraced the role of champion for the underdog and the underprivileged. On the floor of the Senate, he was unafraid to oppose the invasion of Iraq and the conduct of the war.

“How much more of a blank check do you need?” he asked on the floor in 2007. “How many more billions do you have to spend, let alone we’ll never recover the 81 brave men and women who lost their lives – that can’t be recovered.”

Opposed to the war, he advocated for veterans’ benefits and for better equipment, supplies and services for soldiers. In August 2006, for instance, after an Army unit flew back from Iraq to its military base in Indiana, the Massachusetts reservists were told they would have to take an 18-hour bus ride back home. The Army wanted to save the cost of airfare, which was the standard way of getting soldiers home. The soldiers and their families were outraged.

“I think it’s very, very sad that he sacrificed his home, his job, his family and his children for hix country. And this is what they’re gonna give him? They give him a bus ticket. The system stinks.”

Judy Sullivan, the mother of soldier Megan Sullivan, called Kennedy’s office on a Friday afternoon, an unlikely time to get things done in Washington.

“By Sunday morning they had called and said that they did get a plane, and they were all flying home. And Mr. Kennedy himself – I’m getting emotional here – called my house and thanked me for letting him know what was going on, when I and every parent involved was eternally grateful to him for what he did to get my daughter home and all of her friends home.”

A couple days later, when Megan Sullivan and fellow members of the 220th transportation unit flew home to Devens, Kennedy even went there to greet them.

“These men and women are heroes,” Kennedy said. “They've served their country. They ought to be treated like heroes.”

The reception he got from grateful soldiers and their families was unforgettable.

“It's a matter of simple math. You know, from Indiana to Massachusetts on a bus going 60 miles an hour or a plane that goes 600 miles an hour..." The soldiers broke out into applause. "Teddy! Teddy! Teddy!”

He was far more gregarious than either Bobby or Jack. He loved a crowd. Yet he may be better remembered as the state's mourner in chief. No elected official of our time has been better at delivering eulogies, which speaks of a personal burden of having to deliver so many.

Like both brothers, he often quoted the Greeks and classical poets. One poem in particular he invoked in at least several speeches and at two conventions. It was the favorite poem of his brother, the president, expressing the hope that was at the heart of his liberalism.

They are the closing lines from "Ulysses" by Alfred Lord Tennyson:

Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho'

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

This program aired on August 26, 2009.