Advertisement

How Plato Is Helping Women In Poverty

Resume

The statistics don't paint a pretty picture of Holyoke. It has the highest rates of birth, poverty, unemployment and high school dropouts, respectively, in the state of Massachusetts. So why is The Care Center, a Holyoke organization that helps poor women get their GED, using Shakespeare and Plato as their guides?

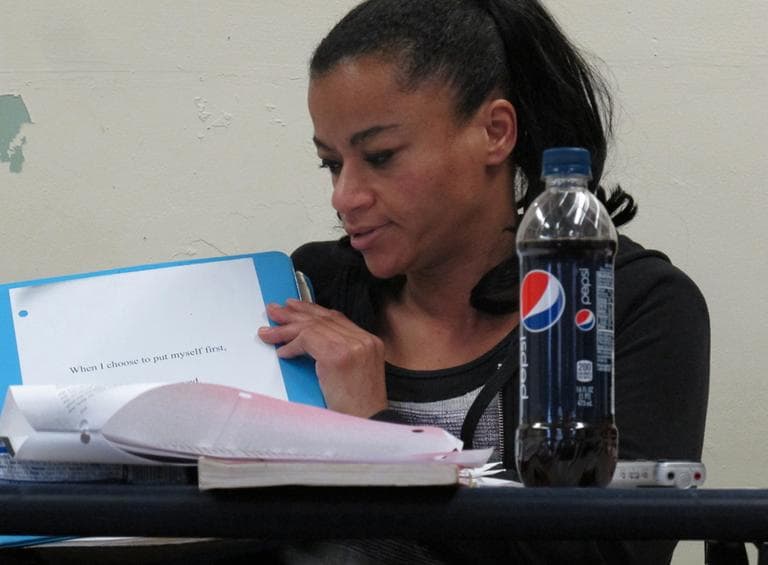

In a basement classroom, about 20 students settle down at their desks. They face each other, but focus keenly on their professor, Kent Jacobson, as he wraps up the semester.

"And we read Plato's 'Cave,' " he recalls, "in which he sees us all living in a cave, staring at shadows and the illusions, and then a few us of trying to dig ourselves up out of the cave into the light."

It's the kind of scene that plays out daily in humanities classes at elite institutions across the country, but talking about philosophy, prose and poetry is radical for this audience.

"I feel like I'm getting into a different culture, and it's interesting," Jacquelyne Segarra reflected, adding, "It's not about Mark from South Boogie getting arrested!"

The rest of the women laugh because they know that neighborhood in Holyoke, and they know that story. Segarra herself was in prison for five years, and, like the rest of the women here, she lives in poverty.

The students in the class range in age from 18 to 57. All are mothers. Some grapple with mental health issues and traumatic experiences.

"I am a survivor of domestic violence," Lisa Darga tells me. Her ex-husband destroyed the 47-year-old's self confidence more than a decade ago, and she's still recovering. But Darga's eyes light up when she talks about her four children. She explains that she's been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and says she never, ever thought she was smart enough for college –- or for anything.

"When you're told constantly you're a piece of crap — you know what I mean? — and that you're never going to amount to anything, you start to believe it," she said. "And for years I struggled with that."

But studying Shakespeare’s love sonnets, or writing her own prose, is changing that.

"I'm liking what I'm seeing in the mirror," Darga admitted. "You know, I'm liking seeing my homework sit on the table and knowing that this is for me."

Darga applied for the class — known as the Clemente Course — after picking up a flyer in her counselor's office. She's seen her classmates transform over the past few weeks, too.

"People who used to be really, really quiet and didn't say anything are now starting to speak, or giggle," she said with a laugh.

Twenty-one-year-old mother Priscilla Rivera relates to that. She admitted writing wasn't her favorite before taking this class.

"Opening up in front of others was not me," Rivera said. "I have a wall with a sniper behind it and it's hard for me to express how I feel and that's what I’m dealing with now — expressing my feelings and how to lay it out."

Rivera wants her 1-year-old son to be able to articulate his thoughts eventually, too. She wants him to go to college.

"I don't know, when I used to think about college I thought it was a waste of my time — I'd rather make money," she recalled, then added with a self-deprecating laugh, "at a freakin' $8-an-hour job!" Rivera's classmates laughed too.

"But I grew out of that," she clarified, "when I got to The Care Center. And then I started this Clemente Course and I met Kent. Hi Kent," she said with a little wave to her professor, then added, "I'm kind of turning red."

Kent Jacobson runs the humanities program at The Care Center and explained the class this way: "When you start reading Shakespeare, and talking about Plato, or reading a Chekhov short story, you quickly realize the concerns that you have — the human concerns you have — are concerns that writers and artists have had for thousands of years."

Jacobson says another benefit for these women is that being here in this class, in this room together, talking about life issues and moral questions, helps them feel less alone.

"When we started this it was with the idea that people in poverty and people of means need the same things, both intellectually and spiritually and physically," said Anne Teschner, executive director of The Care Center. "And over these 13 years we have seen that proven to be true, over and over again."

About 85 percent of the women who take this free, 28-week program go on to pursue degrees in higher education. That success was recognized by the White House with a National Arts and Humanities Youth Program Award last year. Even so, it has been a tough sell.

Anna Rodriguez, the center’s director of education, remembers when Teschner first pitched it.

"This concept of teaching college prep work, or college courses, to students who have not completed their GED and don't have a high school education seemed oxymoronic to me, or mind-boggling," said Rodriguez, someone whose job is to help women who've dropped out of high school pass their GED exams.

But then she observed an interesting effect the class had on her students.

"They were becoming better readers and better writers and that's what the GED is all about!"

But there was something else happening, too.

"Those students were going through a door in which something else was opening up in their brain, something broader than preparing for a GED test," Rodriguez said.

During the two-hour class the women discuss their reading assignment, an essay by Alan Shapiro titled "Why Write?" They also share stories about how what they have learned here is crossing over into their everyday lives.

"I walk around educating everybody because they have to hear it whether they like it or not 'cause I got the biggest mouth in the house," said 43-year-old Tracy Rafferty. She believes she was one of the biggest skeptics of the Clemente Course.

"It really was a joke to me. I'm like, 'Really? I’m not spending two hours on this! I’ve got so much to do, my life is so all over the place!' But it actually calmed me down somewhat," Rafferty said.

And like most of her peers here, Rafferty says she wants to go to college now. But her professor acknowledges that this program is not a guaranteed "passport" to a better life.

"We've had graduates who ended up on the street ravaged by heroin," Jacobson said, "but we've had many more success stories."

Lisa Darga feels successful just completing the literature part of the Clemente Course. They’re also studying American history and next, art history.

"I don’t know anything about art," she confessed, "I can't draw to save my soul. It's a new experience for me, and who knew at 47, with four kids, that I was going to have new experiences?"

This program aired on February 21, 2012.