Advertisement

How Dartmouth's President Is Trying To Cut The Rising Cost Of College

The cost of running a college has far outpaced inflation over the past 35 years. At Dartmouth College here in New Hampshire, costs have gone up tenfold since 1981.

But Dartmouth's president, Philip Hanlon, is trying to tackle the problem. He's committed to transparency in Dartmouth's budget. In fact, last year, he taught a class on the budget.

'Near The Breaking Point'

Hanlon had been wondering why the cost of going to Dartmouth goes up so much each year.

"If you look at any kind of reasonable rate of inflation, what you’ll see is that the costs of higher ed nationally have gone up 2 to 3 percent above that amount for about 40 years in a row," Hanlon said in an interview in his office.

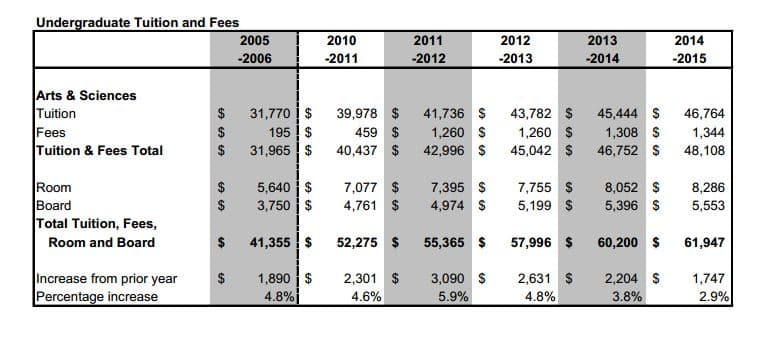

Colleges have covered part of their rising costs by increasing tuition, fees and room and board.

"This historic funding model of having the costs go up that much, the sticker price go up that much, is unsustainable and probably near the breaking point," Hanlon said.

Hanlon is worried that if colleges don't do something about the rising price of college, the government will.

"I think the most obvious comparison is health care," he said, "and health care is another sector where you’ve seen comparable rises in costs above inflation for an extended period of time, and in the health care sector, the government is actively figuring out how they will intervene."

So Hanlon has taken steps at Dartmouth to curtail increases in costs. In the Ivy League, he's taking a leadership role.

"Most of our costs are people," Hanlon said.

Hanlon said overall, the personnel costs have risen with inflation. So he wondered what else could explain the rise in costs and found one factor is more financial aid.

"We have very generous financial aid at Dartmouth," Hanlon said.

But financial aid only accounts for 1 or 2 percent a year of the growth in costs over inflation. That still leaves another 1 percent unaccounted for. Hanlon has concluded that 1 percent can be accounted for like this: Dartmouth, like most schools, keeps adding new programs but doesn't eliminate old ones.

Advertisement

"We have not looked at our current spend and said, 'OK, what’s the least effective 1 to 2 percent of that spend that we can stop doing so we can do these cool new innovations?' ” Hanlon said.

A 1.5 Percent Cut

So Hanlon told each of the schools at Dartmouth — the college, the engineering school, the medical school and the business school — to reallocate 1.5 percent of its spending. Each school must cut 1.5 percent of its budget every year. It can then spend that money on something new. This poses a challenge, especially as Dartmouth looks to replace traditional, less expensive forms of education, such as lectures, with more expensive methods of teaching.

"Think for a moment with me about developing the confidence to innovate and take risks," Hanlon said. "You don’t get that by sitting in a lecture hall and having someone talk to you or by opening up a laptop and watching a lecture. You develop that confidence by trying, by doing, by failing, by being coached, by trying again."

And coaching students requires more interaction between faculty and students than lecturing them. So it's more expensive.

So far, reallocating 1.5 percent of the budget has been relatively easy. The engineering school, for example, has cut the positions of people who have retired from departments it wants to shrink and moved them to departments it wants to grow.

"So if someone with expertise in a general computational area retires, for example, or someone with expertise in optics, what we’ll do is take that position and put them in these other areas — energy and the biomedical area — to be part of our long-term strategic growth," said Joseph Helble, dean of the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth, in an interview here.

At the College of Arts and Sciences, where Michael Mastanduno is the acting dean, some programs in Germany and France are being replaced by programs in Film and Media Studies in Hollywood, Native American Studies in Santa Fe and environmental studies in South Africa.

"Say if there are three and four programs in one area, we might want to reallocate that program, say it’s in Europe, to one in Asia or Africa or some other place where there is increasing student demand, but traditionally, we haven’t had programs, and we use this opportunity to do that," Mastranduno said.

So far, reallocating funding has been relatively easy. But Helble points out that soon, he'll run out of retiring faculty positions to cut. Many of the rest will be tenure-track positions already filled with people not about to retire, and that will make it harder to make cuts.

"Once those costs are associated with a tenured faculty line, you don’t have the latitude to make changes there, and so the fraction of your total budget that can be reallocated is smaller than it would be in the private sector, but it’s trying to help us approach budgeting with the same kind of strategic decision making," Helble said.

Helble welcomes the challenge.

"We’re trying to create a culture where all of us who are heading academic units are doing what we would normally do routinely in the private sector: look at your budget at the end of each year," Helble said. "Ask yourself which investments, which activities are being productive in the way that you had intended and which aren’t core to your long-term mission and then make decisions to reallocate."

Some alumni are also welcoming Hanlon's decision to take on rising college costs.

And Hanlon is getting encouraging results with his experiment. This year, Dartmouth saw the smallest tuition increase since 1977.

This segment aired on February 3, 2015.