Advertisement

CLIMATE CHANGE IN MASS.

Youth Brigade Aims To Close Tree Canopy Gap In East Boston

Resume

Part of a series examining the effects of climate change here in Massachusetts

The dead tree on Meridian Street in East Boston is a metaphor for what's wrong with the urban canopy -- or lack thereof. The trunk rises two stories up, bare to the bone, with a sole branch rising even higher, as if the tree has its hand up, saying, "Hey, who left me here to die?"

Whether the answer is human or environmental, business owner María Monterola across the street wants it gone.

"I would like to see at least one tree per house," she says in Spanish. "That tree last year was looking very pitiful, and this year it died. Maybe it should be taken down and a new one planted."

The sewing machines hum at Monterola's small tailor shop. While working the counter inside, her attention is focused on the street outside.

"I'm a defender of nature, the trees included," she says. "With all the contamination from the cars and everything, the trees capture pollution. ... And then there's the shade."

Visiting the tailor shop are three teenagers, part of a youth-led initiative to increase the tree canopy of East Boston. Youth worker Gabriela Ramirez tells Monterola there’s a simple way to get a new tree.

"It's the city of Boston that has to plant trees here," she says, also speaking in Spanish. "If you want one you can call 311. They will make sure the proper conditions are in place ... but then it will you be your responsibility to take care of it."

Monterola says she’ll call 311 this week -- and hope for the best. (The city says the 1,200 trees its workers plant annually come with a two-year guarantee.)

Seeking To Double Eastie's Tree Cover

In April, 10 high school students started working on the tree project through the nonprofit Neighborhood of Affordable Housing, or NOAH. The project sprouted from NOAH’s climate program. The students are from East Boston, and they see the need for trees every day as they walk along the streets.

The students used Google software to map the tree cover in their neighborhood. They calculated East Boston sidewalks have just 15 percent of the ideal number of trees. Their goal is to double that.

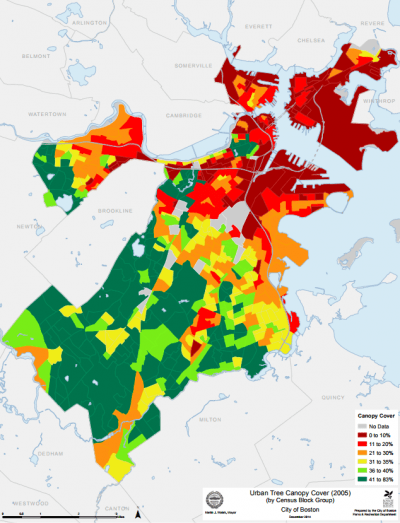

According to Treepedia, a mapping tool produced at MIT, tree canopy covers a bit more than 18 percent of Boston's overall territory.

MIT's Carlo Ratti says trees play a key role in the urban landscape.

"It's about changing the amount of light that is reflected," Ratti says. "It's about evapotranspiration, so making the air cooler. It's about absorbing water when there's a lot of rain."

It's difficult to get a direct comparison on the percentage of tree canopy in East Boston versus the Back Bay, for instance; the city is in the midst of conducting an inventory of its tree canopy. But Treepedia tells a lot. If you zoom in to parts of Meridian Street in Eastie, the canopy is a fraction of the city's overall canopy. Parts of the Back Bay, in contrast, have more than twice the tree coverage of the city.

"It's disturbing to me that in my own community, a street that people walk on almost more than any other street in the city -- one of the main roads in East Boston -- but no trees," says youth tree worker Michael Passariello.

Passariello stands under the dead tree on Meridian Street. He says it's disappointing to see fewer trees in East Boston than in the Back Bay.

"While that may be the more beautiful part of the city, the residents that live here find much beauty in Meridian Street and Central Square, Maverick Square. This is our Newbury Street," he says.

A 3-Pronged Approach

Boston Parks and Recreation spokesman Ryan Woods says many factors go into deciding where to plant trees. They include the availability of tree pits, laws that require a certain amount of space for wheelchairs, and also the willingness of neighbors to have a tree planted in front of their homes.

"Throughout the city we are willing to plant trees wherever there is space to be planted, wherever we have the buy-in from the residents or the businesses in locations that meet the ADA requirements," Woods says. "We will plant anywhere in the city of Boston."

The youth tree brigade wants to push the city to plant 2,000 new trees in East Boston -- and they plan to develop a maintenance route to care for all the trees in the neighborhood. They will do much of the maintenance work, and they see themselves as part of a three-pronged effort to have a vibrant tree canopy in East Boston. The other two prongs are city workers, who will plant the trees, and neighbors, who will care for the trees.

The students give a tour around Eagle Hill, showing off a few trees they’ve taken under their wing. One of them looks parched and was surrounded by litter. Another, just the opposite.

"This is a good example of residential engagement," says youth worker Stephan Marin, looking fondly at the young tree. "It looks like [it was] recently mulched and there are a few flowers. ... So you can assume that the people who live in this house are looking after the street, planting things around it to make it look better."

In its Climate Ready Boston report last year, the city highlighted tree canopy as a major focal point in the fight against climate change.

The report spells out chilling possibilities. The city could see two to seven feet of sea level rise by the end of the century. It means that if nothing is done, huge swaths of neighborhoods — East Boston and the Back Bay alike — could be underwater.

Trees alone can’t stop that. But they do provide valuable mitigation against extreme heat and absorb stormwater to prevent flooding.

Engaging The Community

Kannan Thiruvengadam runs Eastie Farm, a small garden in the thick of a street of triple deckers near Maverick Station. He says the health of the tree canopy will depend on engaging the community.

"When the city planted all these trees last year they expected the community to water," he says. "And the community did not have any idea about this.

"In my mother tongue, Tamil, there is a proverb that says whoever plants the tree is going to water," he adds with a chuckle. "It's not quite true here."

Thiruvengadam points out that other types of vegetation, like all the plant varieties growing in his garden, provide similar benefits to trees. And some of those benefits go beyond the environmental.

He likes to tell the story of two neighbors abutting the garden. Both directed their downspouts toward the garden — the rainwater is collected in barrels and on a good year provides enough H2O to water the plants. The garden has addressed the problem of basement flooding for the two neighbors. It’s also brought together an Italian family and a Salvadoran family.

"And if you know something about East Boston's history, the Italians were here much before the Central and South Americans got here, so there's that perception that 'they are the immigrants and we are the natives.' But this is a space you will see that people come together and shake hands and work together," he says.

And that sense of community, Thiruvengadam says, could be one of the most important weapons in the battle against climate change.

Correction: An earlier version of this post incorrectly spelled Gabriela Ramirez's name. The post has been updated. We regret the error.

This segment aired on July 5, 2017.