Advertisement

Reporter's Notebook

In Puerto Rico, 'Help Has To Be Ongoing' To Prevent Exodus

WBUR's Simón Rios and photographer Jesse Costa were in Puerto Rico, reporting on the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. Simón's dispatches are here, with the latest on top. See here for more of Jesse's photos from the island.

Monday, Oct. 16 — 5 p.m. EST

Friday, Oct. 13 — 8:50 p.m. EST

Four days into our travels around a hurricane-ravaged island, we thought it couldn’t get any worse. We’d been to the mountains and we’d been to the shoreline, and the destruction is varying but constant. Still, we weren’t prepared for the kind of total devastation that the municipality of Humacao had suffered, in the southeast of the island where Hurricane Maria first made landfall.

Constantly hunting for Massachusetts connections, the plan was to find the mother of a friend of mine from Boston, who’d recently married a Puerto Rican man and moved to the town of Punta Santiago. The problem is there’s no phone communication there, and not until we were on the road to Punta Santiago did we get word that she wouldn’t be around to receive us.

We met up with an organization called PECES, which was founded by an American nun in 1985 and has deep roots not only in Humacao, but throughout the region. The first tape I collected was of a large prayer circle, 30 people maybe, who joined hands and listened to a health care worker talk about their plans for the day. The brigade consisted of doctors, nurses, social workers and regular volunteers who’d come to PECES to determine how best to enter Punta Santiago and provide services to the people of the town. Horror stories abound, like the man who didn't get help in time after his legs were cut by a flying zinc roof, and who had to get them amputated in the end. These volunteers are trying to prevent those kinds of situations, sending brigades of doctors and nurses into some of the hardest hit neighborhoods.

We hopped in a truck with one of the PECES leaders, who drove us along the coast and narrated the day of the hurricane. The ocean was so powerful that it lifted the town dock — used by the fishermen of Punta Santiago — and deposited its planks all over town, including in the front yard of his uncle several hundred yards away. On the beach, he told me how vital it will be to stimulate the economy here, which relies largely on tourism — if not, many many people will be forced to flee to the mainland.

This is a recurring theme in Puerto Rico. Almost none of the businesses in Punta Santiago were open, and nobody was enjoying a beach that I imagined in other times was a paradise. It was blazing hot and the place felt like a ghost town despite the fact that it had not been abandoned. We talked about the federal government’s response — he said he called FEMA days after the hurricane to help coordinate efforts (the idea that large government organizations from outside partner with community groups to determine how best to distribute aid) but he said FEMA never called back.

We talked to two young Puerto Ricans who were removing all the sand the ocean had thrust up onto the street next to the beach, and when they walked away with their tools in hand and sombreros on head, Jesse Costa (our photographer) spotted a Puerto Rican flag in a doorway, stopped the car, and triangulated a shot of them walking past the one-starred flag. (I thought how easy it would be for young men like these to pick up and leave to a place like Orlando or New York, but if they do, who’s going to rebuild Puerto Rico? Most everybody I talk to says they're deeply proud to be Puerto Rican and they don't plan on going anywhere.)

We drove through a part of Punta Santiago that’s situated between the ocean and a channel of water. When flooding happens here, the water has nowhere to escape and flows into the neighborhoods. I’d been in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and the devastation near the water in Punta Santiago was on the same level.

One of the saddest sites: A woman sitting behind a bucket and washing silverware — one of the few things that were salvageable — her house reduced to a festering unlivable pile of material. She stood and told us her husband had a brain hemorrhage and was hospitalized before the storm. Then came the winds and rain, and he had to be transferred to a medical ship operated by the military. She started crying as she told us she hadn’t been able to reach him since before the storm. She had no family in San Juan to check in on him, and she had no way of getting to see him, which after suffering the most brutal hurricane in the history of Puerto Rico, was the only thing she wanted to do.

House after house after house, everyone has stories: people’s cars totaled, people’s houses swelling at the seams, people’s worldly possessions soaked with contaminated water and sitting in stinking piles in the hot sun. These people were already poor, and now the hurricane has taken everything from them, and there’s no work to earn the money to reconstruct.

Back at PECES, we met two North Americans: a wiry woman from Houston with spiky hair and neck tattoos who’d come as a sort of disaster relief vigilante, and a wide-eyed shiny bald commercial airline pilot based in New York who’s hoping to establish an “air bridge” of aid to Puerto Rico. They say they’ve arranged to travel to Ponce in the south, beginning at the airport as supplies come in, then do a “ride-along” with government groups to the villages to make sure the goods aren’t lost to “corruption.” They were in Punta Santiago talking to Sister Nancy Madden, the founder of PECES, about how they could help.

Madden spoke rapid-fire English: so much to say and so little time. She says Maria brought one of the most severely traumatic experiences anybody could live, and practically the whole island lived it.

“Help has to be ongoing,” she said. “It’s not going to help to have water for one day and not have water for the next week, it’s not good enough to do have food for one day and not have it for the next week, it’s not going to help if you lost your job and you can’t find another job.”

Madden told me Puerto Rico needs massive help to return to normal — and thus avert a massive migration of Puerto Ricans from places like Punta Santiago.

“There’s a whole exodus from Puerto Rico that we can’t let happen,” she said.

“People are desperate. We have to say there’s hope here, there’s a reason to live here. It’s a beautiful island with beautiful people — some of the best people in the world.”

Friday, Oct. 13 -- 10:30 a.m. EST

Listen here to Simón's feature on Puerto Rico's symphony coming back together:

Thursday, Oct. 12 — 9:20 a.m. EST

We left our place in San Juan yesterday and headed out to meet with leaders of an organization called Proyecto Enlace Del Cano, one of several groups receiving money from Massachusetts United For Puerto Rico. That’s the group set up by Boston-area Puerto Rican leaders -- endorsed by The Boston Foundation and the mayor and the governor -- which has already surpassed its $1 million fundraising target. We want to see where donations from Boston are ending up, and talk to the people doing the work, as well as those getting help.

Proyecto Enlace is a sort of quasi-governmental organization dedicated to eight communities that border a natural channel of water that runs through part of San Juan. These neighborhoods are populated by low-income Puerto Ricans, many of African descent, and their homes are constantly at risk of inundation due to their proximity to the water. Executive director Lyvia Rodriguez led us on a tour of several of the neighborhoods, introducing us to families that had lost everything and that were now receiving help from Proyecto Enlace. The help came in the form of tarps -- originally donated by FEMA and a nonprofit based in New York (they said the New York tarps were higher quality). If you can imagine living in a house without a roof, a tarp becomes one of your most valuable acquisitions.

In the afternoon we traveled west to the municipality of Loiza, which like so much of this island was slammed by Maria.

In Loiza there is a group called Taller Salud, or health workshop, dedicated to the empowerment of women in the areas of reproductive rights and healthy sexuality. They're also set to receive money from the Boston initiative, and so the ladies had shifted their regular agenda to deal with problems related to the storm. They showed us their office in Parcelas Vieques, which has been transformed into a donation processing center.

Then we traveled to a town called Pinones where Taller Salud had helped set up a community center, with a community kitchen that offers hot meals three times a week, and even a zen-like space where people can get massages and acupuncture.

One of the women coming out of an acupuncture session said she lost everything in the hurricane -- her houses and all her possessions. She had a bad case of arthritis in her knee and said acupuncture alleviated her pain, allowing her to stretch out limbs that had been so swollen she couldn’t extend them all the way.

She told us she was deeply stressed, not only by her own situation, but by spending her days helping other people. A Maria survivor helping other Maria survivors.

So many of the organizations that work on social justice, on environmental protection, on women’s rights and other causes, all these groups are now dedicated to disaster relief. If their primary goal is to help people, they’re spending these days helping folks get tarps for their roofs, food for their bellies and water that’s safe to drink.

Today we’re off to Humacao, a town called Punta Santiago, to try and find the mother of a friend of mine back in Boston. Apparently she’s OK, but the area -- coastal, on the southeast of Puerto Rico — was one of the hardest hit by the hurricane, which made landfall there.

Wednesday, Oct. 11 -- 8:30 a.m. EST

We woke up at 6 a.m. yesterday and headed for breakfast around the corner at a place running on gasoline. On the plane to San Juan, a Puerto Rican woman who noticed my NPR T-shirt stopped me to quiz me on our plans. It turns out her plans were far more interesting.

Ivonne Beltran had practiced law for three decades on the island before moving to the Boston area — Revere, to be specific — and now she was going back to check in on her properties and her family. We agreed to meet off an exit in Arecibo, and travel to an oceanfront property in a town called Islote. It seems the design of the property, with a large knoll up against the beach, spared the three houses she rents on the small piece of land. There was significant damage to the wooden structure, but the two cement structures were almost untouched.

From there we hopped into her pickup truck and headed to the municipality of Corozal in the interior of Puerto Rico, not far from San Juan.

The entire way our mouths were agape at the level of destruction. It seems everything that wasn’t bolted down was ripped away by the hurricane winds -- can you imagine up to 175 mph wind? It was like this the whole way, but when we entered the mountainous area, it was worse. You couldn’t drive for five seconds without taking in some new scene of destruction: the trees defoliated, the wooden houses reduced to rubble, bamboo snapped in half, utility poles pushed off their axis or snapped entirely -- a spaghetti of electrical lines on the side of the road, or running across the road.

By now the people (and I use this word exclusively) had cleared the roads in their neighborhoods -- the force of thousands of Puerto Ricans in the days after Maria allowing us to traverse the countryside. I can’t count the times I asked Ivonne to stop so we could take pictures and talk to people, about how they’d lost everything they owned, about how they said no single government official -- not FEMA, not the governor’s office, not the local mayor -- had stopped by to check on them.

One house we saw was reduced to its studs, and the only thing left was a shiny white toilet bowl.

Ivonne surveyed her properties, which had suffered relatively little damage, and the damage done was largely taken care of by her “Jibaro” cousin Edwin. But when we started talking to her uncles and her cousins, they were devastated. One of them operates a food stall on a beach that was upended by the hurricane, and he was crying as he told us how much he wanted to get back to work. Another cousin told us that even though he has a good government job -- which is suspended because his office has no electricity -- that he wants Ivonne to help him find a way into the States. He was a hearty young man, probably 45 years old, and I thought to myself that if people like this are leaving Puerto Rico, who’s going to rebuild the island?

Finally we went to a lumberyard in Corozal that Ivonne said had formed the foundation of her family’s success -- what allowed her to go to college and practice law, and similar stories for other family members. Now it was in ruins, like much of Puerto Rico is in ruins, and she said it has all depressed one of her uncles to the point of attempting suicide.

Ivonne told me her job was to cheer people up. You can’t underestimate the importance of a positive attitude, but the people here are going to need a lot more than good spirits.

Tuesday, Oct. 10 — 10:30 a.m. EST

We arrived in San Juan yesterday on a flight from Boston that was only about half full.

We visited a neighborhood called Juana Matos, in the municipality of Cataño, that reeked of rotting garbage, apparently because of a backup in the waste disposal system. A community leader there, Pedro Carrión, told us he is concerned for the public health risks this poses, in addition to stagnant water all around.

Eighty percent of the homes have been partially or completely destroyed. The neighborhood is adjacent to a conservation area, which also suffered heavy damage. Several of the people we spoke to had lost much of the structures of their homes -- some had been reduced to piles of rubble -- and all the belongings inside.

But there seemed to be widespread optimism, smiles in the face of adversity and the belief that aid is arriving to the island but not made its way to the communities. Everybody we spoke to in the village vowed to rebuild.

Despite the stoicism, we were told that at night you can hear people wailing, unleashing their emotions after maintaining a smile throughout the day.

One of the organizers who is raising money in Boston for Puerto Rico, Pedro Reina Perez, invited us to stay in his apartment in the San Juan neighborhood of Miramar. He asked me to bring batteries to his mother so she could listen to her radio. We dropped the batteries off and used my phone to call Pedro, whom she had only spoken to once since the hurricane. She was lighthearted and joked about what a good time she was having -- sleeping 14 hours and receiving lovely visitors like us -- but tears were close to the surface.

Pedro is hoping to arrive this week, and he wants to take his mother, who’s 81, back with him to Boston -- at least until some basic things are restored on the island.

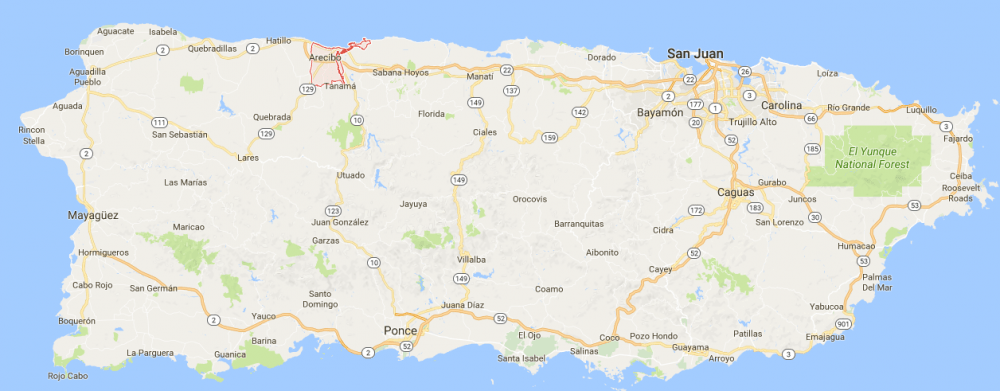

Today we are headed to Arecibo (see the map below) to meet a Puerto Rican woman from Revere who is checking in on her property there. She brought with her on the plane a chainsaw and $300 worth of nails. I'm hoping to find out what they will be used for exactly.

This article was originally published on October 10, 2017.