Advertisement

Analysis

24 Percent Of 7th District Primary Voters Had Not Voted In Previous 5 Primaries

U.S. Rep. Ayanna Pressley, who was sworn into office Thursday, touted her campaign’s ability to “expand the electorate” in her convincing September primary victory over longtime incumbent Michael Capuano. And an original analysis finds that new voters did indeed show up in a major way, led by turnout among young people.

“We built a movement,” Pressley told WBUR shortly after the win. “This was a people-powered, broad, deep, diverse and grassroots coalition. … It’s so critical that we [were] intentional about engaging new voices.” (Capuano, for his part, also cited first-time voters, and said he hopes they continue to turn out.) In interviews, Pressley and her top staffers described their strategy to bring new or infrequent voters to the polling booth: a smart and relentless social media presence, a focus on ethnic media over traditional outlets and old-fashioned shoe leather campaigning.

So what does the data say? Was the Pressley campaign successful at mobilizing significant numbers of first-time or infrequent voters?

The answer, of course, depends on how you define a “first-time” or “infrequent” voter. A MassINC Polling Group analysis of voting patterns over the past four election cycles, using the 2018 Massachusetts voter file from The Novus Group, sheds some light on the situation.

It’s a truism of politics that presidential election years drive more turnout than other election years. Thus, when comparing across elections, it’s helpful to compare midterm years with midterm years, for instance. So for 2018, the most direct comparison is the 2014 midterms.

If the Pressley campaign was banking on turnout, they certainly cashed in. Some 106,556 voters in the 7th Congressional District cast ballots in the 2018 Democratic primary, compared with just 61,725 in 2014 (a year Capuano ran unopposed), according to official election results. And among the district’s 2018 primary voters, only 37 percent had also voted in any 2014 primary, according to voter file analysis.

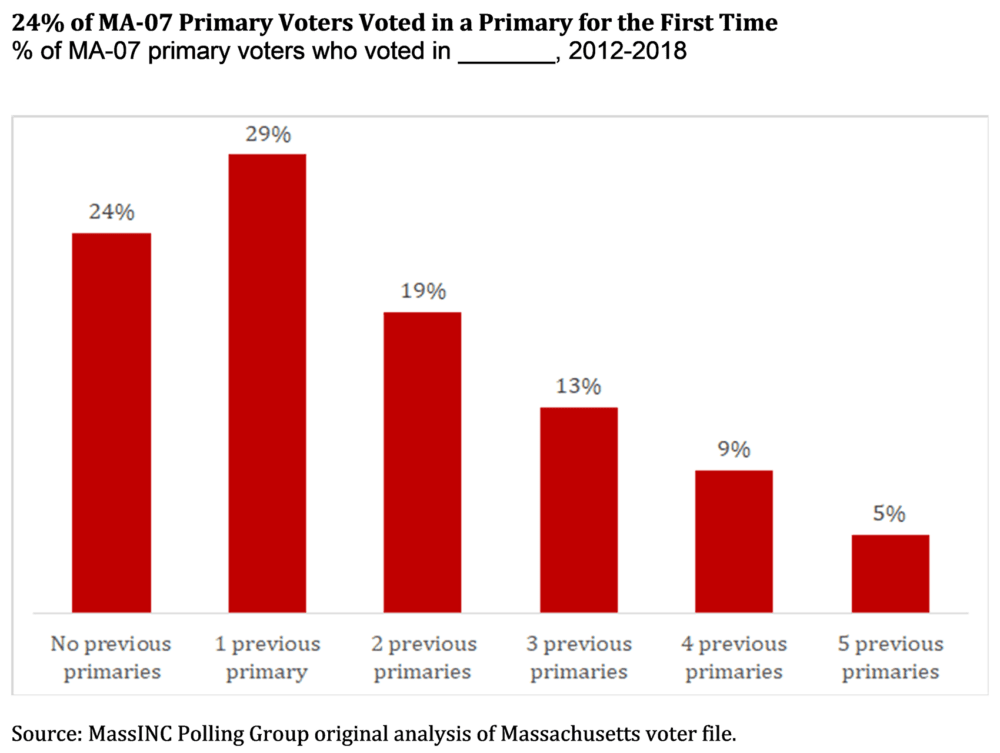

Another truism: Primary voters are a different breed from their general election counterparts; they tend to be the real political fanatics. Massachusetts holds separate primaries for presidential candidates and for other statewide offices. If we only consider statewide elections, 50 percent of 2018 7th district primary voters had not voted in any of the previous three September primaries dating back to 2012, the first election cycle for the redrawn district. Including presidential primaries, 24 percent of 2018 primary voters had not voted in any of the previous five primaries.

For the Pressley campaign, this is the notable group — getting people involved earlier in the political process than they had been before. This 24 percent of voters will be our focus. For ease moving forward, we’ll refer to them as "first-time voters."

So who were these first-time voters? Well, they were predominantly women and young people: Fifty-five percent were women, and 66 percent were age 44 or younger (including 34 percent who were 18 to 29 years old). This surge of young, first-time voters increased the overall proportion of voters 44 or younger from 25 percent in 2014 to 42 percent in 2018. Combining age and gender, women ages 18 to 29 made up the largest group of new voters, at 20 percent.

Advertisement

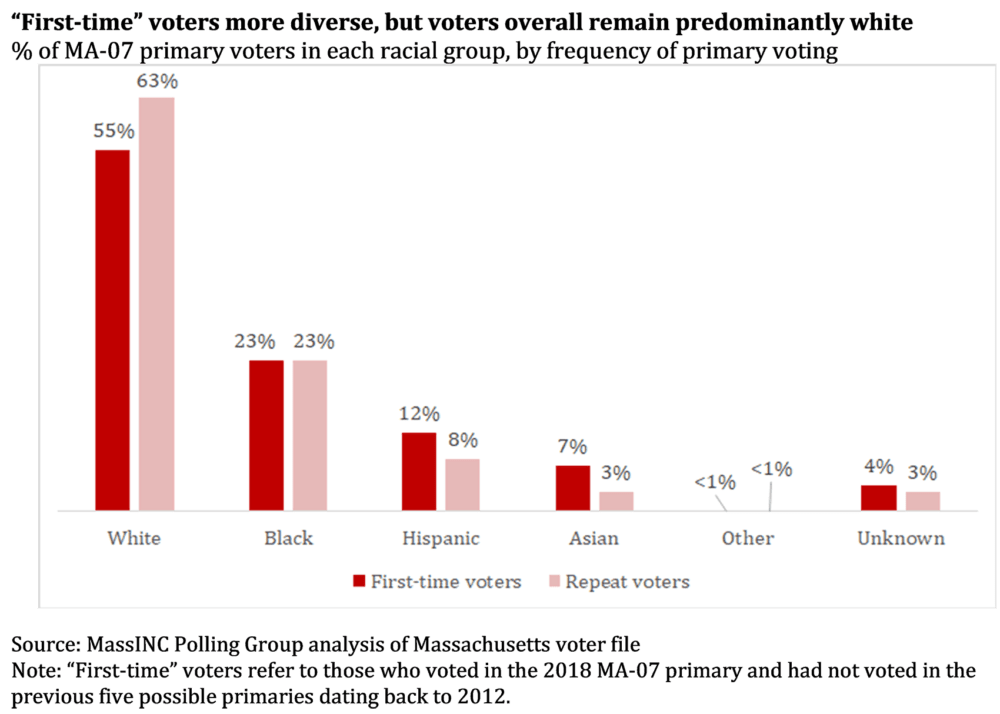

When it comes to race, first-time voters were more likely to be Asian or Hispanic, compared with the 7th’s repeat voters. Among first-time voters, 7 percent were Asian and 12 percent were Hispanic, versus 3 percent and 8 percent of repeat voters, respectively. Meanwhile, 55 percent of first-time voters and 63 percent of repeat voters were white, while 23 percent each were black. (For reference, in no other Massachusetts congressional district were black voters more than 4 percent of all 2018 primary voters.) So while this turnout indicates a more diverse electorate in 2018, the state’s only majority-minority district still has a predominantly white voting base.

A note on race assignments in voter files: Voters are not required to provide racial information when they register to vote. Thus, commercial voter files use other indicators — such as surname, address and neighborhood composition — to make educated guesses about a voter’s race. So any discussion of demographics based on voter file analysis should be taken with a grain of salt. For this analysis, 3 percent of 7th district primary voters did not have an assigned race (including 4 percent of first-time voters and 3 percent of repeat voters). (For more information on the accuracy of demographic assignments in voter files, Pew Research Center has a useful report.)

A last truism of politics: Elections favor incumbents. But the surge of new voters in the 7th primary shows how challengers can bring attention to a race, challenge assumptions about those in power, and even engage dormant groups in the political process.

The race for the 7th was notable for a number of reasons — not least the election of Massachusetts’ first black woman to Congress. But among these reasons, we should also count the mobilization of new voters. Whether these newcomers make voting a habit remains to be seen. But a slew of upcoming Boston city elections and, of course, the highly anticipated 2020 presidential race will give them their chance.

Maeve Duggan is research director at the MassINC Polling Group and a contributor to WBUR. She tweets @maeveyd.