Advertisement

Beyond The Suffering: A Deeper Look Into Frida Kahlo's Necessary Artistry

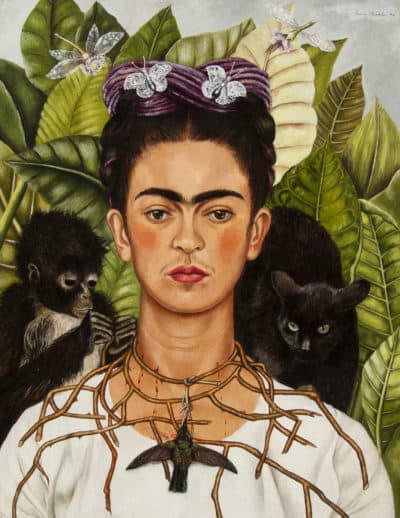

One of Frida Kahlo's seminal paintings remains the resplendent "Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird," in which the artist stares stoically ahead as a thorn necklace carves into her neck and blood trickles down her bust. A monkey sits on her right shoulder, pulling the necklace, which snakes down her chest like the roots of a tree. A dead hummingbird dangles from the thorns.

Kahlo is positioned in front of lush, richly hued fauna, with buoyant dragonflies (or perhaps just flowers with wings?) floating above her head. There's a bittersweet contrast in that lavish, natural background and the cutting death of the foreground.

All while Kahlo confronts us straight ahead with her unruffled stare — as if pain has forced her to numbness.

Scholars have fretted over the symbolism in this painting. The hummingbird could represent Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec god of war or perhaps just a love charm? Her husband, the famous painter Diego Rivera, gifted her a monkey, so could the animal symbolize how Rivera imposed suffering on her?

It's this obsession with Kahlo's biography and how these events come through in her art that dominates the narrative about her. Even the scholarship about Kahlo centers — almost voyeuristically — on the tragic experiences of her life more than her artistry.

We imagine her affairs with women and men, her tumultuous marriage to Rivera, that tragic bus accident that left her in chronic pain all of her life. There's a compulsion that's satiated only through consuming Kahlo's agony.

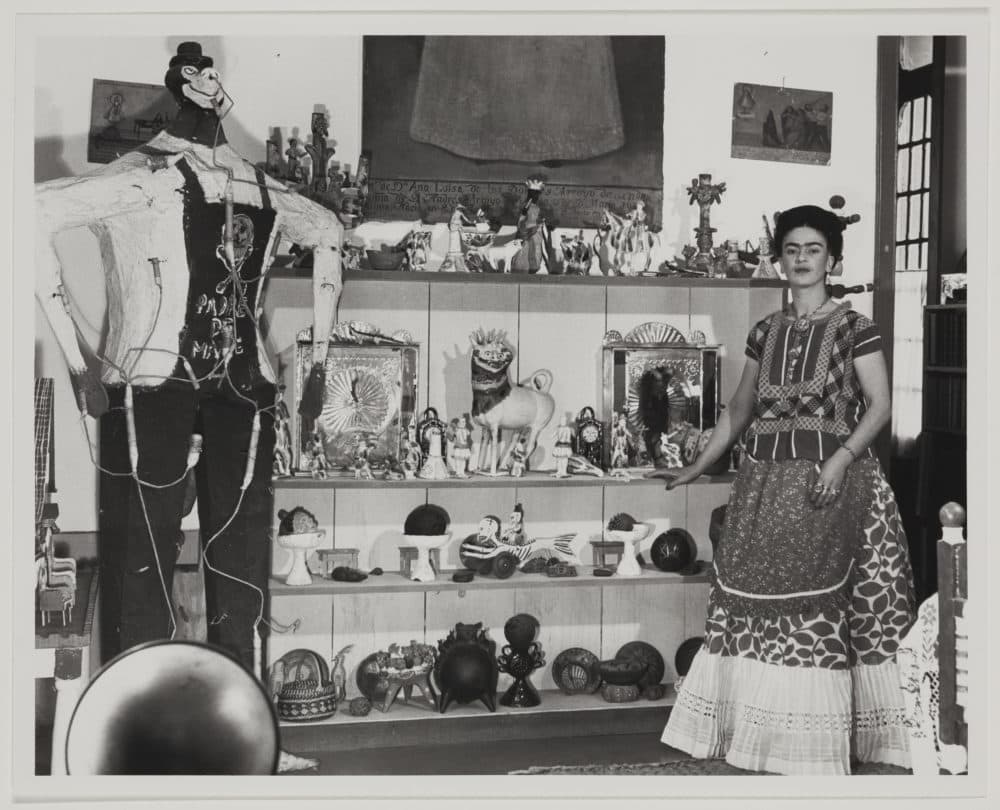

The Museum of Fine Arts' "Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular" offers a deeper, more rigorous appreciation of Kahlo's artistry that strays from the overused trope of an artist in anguish. Layla Bermeo, the museum's Kristin and Roger Servison assistant curator of American paintings, has brought together eight Kahlo paintings from various public collections in the U.S. with 40 objects of "arte popular," or Mexican folk art.

"Collecting arte popular was in itself a political act," Bermeo said in a recent interview. "It was a way to embrace art forms that developed outside of European style institutions — a way to think about a Mexican history that did not simply privilege a European past."

Kahlo collected these decorated ceramics, embroidered textiles and artisan toy objects, made by indigenous communities almost always in rural Mexico. She also wore indigenous clothing — a statement that in modern times would be condemned as cultural appropriation, but that in Kahlo's era was a symbol of political solidarity.

Kahlo — part of a thriving modernist scene in the '20s and '30s — was deeply influenced by arte popular. After the 10-year Mexican revolution came to a halt in 1920, both artists and politicians sought unifying national symbols. Indigenous craft art came to imbue "Mexicanidad," a uniting national culture. Kahlo would implicitly or sometimes quite literally reference it in her work.

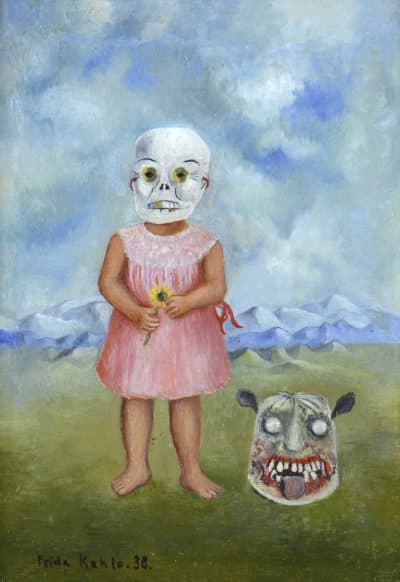

In "Girl With Death Mask (She Plays Alone)," Kahlo painted a small child holding a yellow flower, wearing a skeleton mask with a jaguar mask to her right. At the MFA, Bermeo positioned an actual jaguar mask made in late 19th century Mexico — a common object of arte popular — next to the iconic painting. "Girl With Death Mask (She Plays Alone)," is painted on a metal support, a direct reference to arte popular and a testament to Kahlo's thoughtful technique that's so rarely explored.

How easy, also, it is to assume that Kahlo's insistence on painting children stems from her own miscarriage or lament of not having children. But at the MFA, Bermeo offers a deeper, art historical understanding: Themes of childhood were a common area of interest for the global modernist movement in the '30s.

Advertisement

"For someone who is arguably the most famous painter to ever come out of the Americas, Kahlo doesn't really have a place in a lot of 101 art history classes," Bermeo told me.

In one of the most visually striking pieces of the exhibition, "The Suicide of Dorothy Hale," Kahlo takes aspects of the ex-voto, a Catholic folk art tradition that celebrates miracles, and subverts it by showing tragedy: the suicide of a socialite who jumped off her luxury apartment building in New York City. In "My Grandparents, Parents and I," Kahlo also utilizes the ex-voto aesthetic to celebrate her family tree — German and indigenous ancestry — at a time when Nazis were using similar paintings to prove ethnic purity.

What floors me about Kahlo's work is the enduring power of her political voice. At the MFA, the exhibition begins with "Dos Mujeres," the painting owned by the MFA. It shows two indigenous or mixed race domestic workers painted in the classical portraiture style. "Dos Mujeres" was also the first painting Kahlo ever sold in 1928. It marks a seminal moment. Though her artistry is still in its infancy — there's a lack of spacial depth and detailed facial expression that's present in her later work — it's so clear she has something to say: The poor, the indigenous deserve to be painted with dignity.

Look no further than the racist and classist vitriol in Mexico against "Roma" star Yalitza Aparicio, the first indigenous woman to be nominated for an Oscar, to understand how necessary Kahlo's work remains.

"Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular" will be on view at the Museum of Fine Arts through June 16.

This segment aired on February 27, 2019.