Advertisement

Future Of Food

Invasive Species For Dessert? Food Makers Hope 'Future' Sweets Get Us Talking About Climate Change

Our shifting environment’s impact on what and how we eat is one of the most urgent issues of our time. But how do you encourage people to think and talk about what our food might be like in a warmer future?

Local designer and researcher Keith Hartwig believes one answer is to have them taste it for themselves.

He’s been searching for ways to engage people's senses as they contemplate the relationship between climate change and local food systems. His latest experiment is part of a new exhibition titled, “Untold Possibilities at the Last Minute,” now up at Cambridge City Hall Annex.

With his teammates Matthew Battles and Jessica Yurkofsky at Harvard's metaLAB, Hartwig created interactive, public tastings — dubbed "FUTUREFOOD" — to pair with the exhibition.

Before the tastings were set, Hartwig and his colleagues asked area chefs and food producers a few questions about the environment, sustainability, food equity and waste. Then, Hartwig's team issued three-word prompts to get the makers’ creative juices flowing.

“One is invasiveness,” Hartwig said. “One is involved — which is to think about how we can start working with communities to address these questions. And the third is invisible — so what are the sort of invisible or hidden effects of climate change on the food system?”

To show us what they came up with, Hartwig and some of the producers gathered at Toscannini's in Kendall Square. That's where the renowned ice cream shop's co-founder, Gus Rancatore, had taken on a provocative ingredient.

“He’s using Japanese knotweed — which has become a symbol of invasiveness — and a plant that has grown prolifically as a result of environmental disruption and climate change,” Hartwig explained. “But it’s a plant that actually is full of nutrition and has a lot of opportunities in terms of the way that we might start thinking about it as a future food.”

Rancatore stood over a gas range in his shop’s kitchen stirring a sugar syrup.

“So what we're going to do today is make knotweed sorbet,” he explained. “And we're actually making this for the second, possibly the third time, because we want to improve the texture.”

Rancatore needed to get the sorbet just right for his FUTUREFOOD event. (The tasting was held on May 25.)

“Knotweed is your prototypical invasive species that grows everywhere — wiley and recklessly,” he mused. “The idea that we might be able to get some benefits from it I thought was interesting. It's also an example of how everybody in the food business has to adapt to a changing environment.”

The longtime ice cream expert enlisted local foragers to get early season knotweed, because it tastes better.

“This is the distillation of a week's-worth of work by five people who brought us 100 pounds of knotweed they harvested from wildlife areas,” he recalled. “We cooked it down, and we pureed it, and we sieved it, and we got this exotic mucilage — to use the word you don't get to use too often.”

Rancatore added applesauce to the mixture, giving it an earthy, greenish-brown color — kind of like camouflage. He thinks the feral, herbaceous blend tastes kind of like a funky applesauce.

“I don't think this is something that's going to work its way into supermarket freezers,” Rancatore said. “I think this is an interesting project that makes you think about changes in the environment and changes in American food ways.”

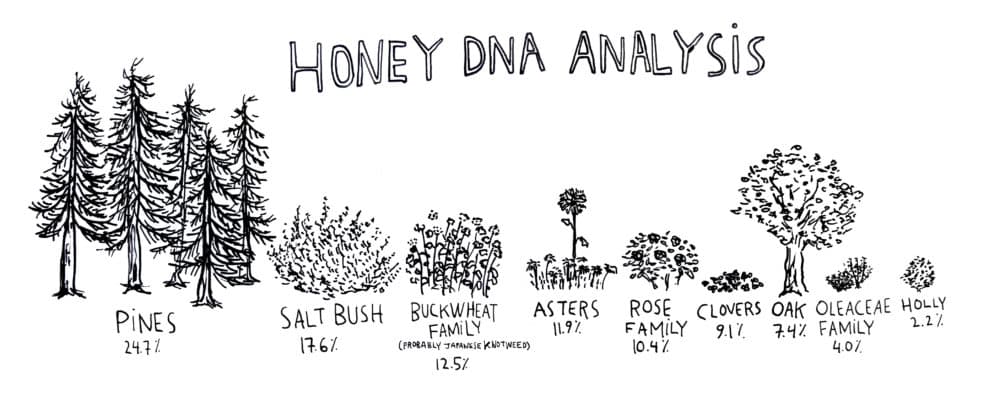

Boston chef Nate Phinisee’s FUTUREFOOD assignment was to highlight invisible forces that guide our food. He worked with five different varieties of locally-harvested honey to create toffee and “honey waters.”

Hartwig said Phinisee’s culinary investigations allow people to taste how each honey’s unique flavor profile, “and to consider their relationship to the broader ecology of our region.”

Phinisee twisted the lid off a jar of candy he made and popped one in his mouth.

“They’re definitely toffee consistency,” he shared, “and they’re very sticky.”

To make the candy, Phinisee used Boston wildflower honey and nothing else. The effect is potent and pure.

His sipping sampler – or flight — of waters consists of diluted honey from basswood, clethra, black locust and knotweed.

For the public tasting on June 15 he plans to wrap the toffees in edible flowers to make them more aesthetically pleasing, but also to force people to realize the interconnectedness between local bees, local plants and our local ecosystem.

Global bee decline has been linked to climate change, widespread pesticide use and industrial agriculture. According to recent research, local crops including apples, blueberries and cranberries will be threatened without the pollinating power of a healthy bee population.

Phinisee hoped his candies open the door to deeper dialogue about these issues.

Advertisement

“The toffee is a kind of easy way in,” he explained, “because you just eat a piece of candy, and that gets you into a broader conversation about bees — what they do for plants, wildlife and everything that we see around us — because they are, hopefully, part of the future.”

At the library event, honey tasters can check out information and illustrations about bee habitats in Boston. A representative from the Best Bees Company will also be on hand to talk about beekeeping, bee health analysis and urban ecology.

Another confection at one of the tastings was crafted by a pair of entrepreneurial doctoral students at Tufts University’s Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy.

“We’re thinking in the big picture in how the products that we make affect the whole food system and the health of our customers,” Sylvia Berciano Benitez said.

She and Nayla Bezares co-founded Baravena, a new sustainable, vegan spin on Latin ice cream, or helados.

They're using climate-friendly oats instead of milk or cream because they said dairy cows are big contributors of greenhouse gases. Bezares described how the production of other plant-based alternatives — like almond or coconut milk — deplete the planet.

“Coconuts are imported from far, far away. They’re high in saturated fat and have a strong flavor,” she said. “Nuts on the other hand, most of them are grown in California, but they require a lot of water, and California, as you know, is already suffering a lot from water stress.”

Bezares said oats are grown all around the U.S. and need less water.

For an exhibition event in May, the duo designed a special helados with sesame brittle and a more common ingredient: bananas.

“[Bananas] make fruits accessible to a lot of people, they're part of a lot of desserts that we choose, but we don't grow any of them here in the United States,” Bezares said. “And so we hope that we can use that as an opportunity to highlight the fact that every day we're faced with choices that can help perpetuate the challenges that we already face in our food system.”

While not in stores just yet, Baravena's portfolio of flavors includes horchata, choco-churro, fruta pasión and guava.

Frozen desserts and candy are surely some sweeter ways to help the medicine go down while people consider the harsh realities of climate change. The collaborators hope more people will be inspired to create their own solutions for a more sustainable menu in the future.

The final FUTUREFOOD public tasting — of honey toffee and honey waters — will be at the Cambridge Public Library on Saturday, June 15, as part of the city Arts Council's climate change exhibition: “Untold Possibilities at the Last Minute.”

This segment aired on June 6, 2019.