Advertisement

In 'Our Parents, Ourselves,' Two Photographers Turn A Lens On Mom And Dad

We are all somebody’s child. Maybe we bonded closely with that someone, or maybe we didn’t. Maybe we consider that someone a best friend or maybe a burden. That someone might have been nurturing, or needy, encouraging, or deflating.

In the case of photographers David Hilliard and Sage Sohier, that parental relationship has been front and center, and is the subject of “Our Parents, Ourselves,” an exhibit on view at the Fitchburg Art Museum beginning Sept. 7 plumbing the complexity of the parent-child bond while exploring concomitant issues around aging, parental expectations and ultimately mortality.

“My dad has always been the most central key figure in my life,” reflects Hilliard. “I had two great parents, but my father's always been the one that has understood me in a more complex way… We've always had a really great relationship — not without its complications, like any relationship with a parent.”

For Sohier, mom was the key reference.

“There would be generational differences that we had,” says Sohier. “My mother was born in the late 1920s and grew up in the 1930s and ‘40s. Growing up in the ‘60s, suddenly the possibilities seemed different. The ways in which my mother was grooming me and my sister seemed irrelevant.”

Independently of each other, Hilliard and Sohier have spent decades documenting their parents in the midst of quotidian activities such as bathing, swimming, applying makeup and reading in bed. Hilliard, regular visiting faculty at Harvard University, School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts, MassArt and Lesley University College of Art & Design, followed his “regular guy” father, Ray Hilliard, a factory worker who was, according to Hilliard, “the kind of lower middle-class guy that you could easily overlook.”

Sohier, who has taught photography at Harvard, Wellesley College, and the Massachusetts College of Art, fixed her camera’s lens on her fashion model mother, Wendy Burden, who made life fun for her children and who also happened to have a natural ability to strike the perfect pose.

Hilliard’s father and Sohier’s mother were distinctly different in personality and station in life. Hilliard’s father lived in Lowell. He smoked cheap cigars, drove a pickup truck, wore Hawaiian shirts and read Playboy magazines. He was the rowdy, good-time guy who Hilliard describes as “a little rough around the edges.”

Hilliard’s father divorced his mother when Hilliard was young, although Hilliard saw his father on weekends and summer breaks. On those weekends at his father’s house, it was “anything goes.”

“We get to the house and we could take off our clothes and run around naked and do whatever we wanted,” says Hilliard. “We were like feral cats.”

Advertisement

Sohier’s mother, on the other hand (also divorced when Sohier was young), lived in the well-to-do suburbs surrounding Washington, D.C. She was poised and patrician and had been discovered in her youth by photographer Richard Avedon, leading to a career as a model seen in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. Sohier’s mother was always worried about what would become of her two gangly daughters who were a bit too tall, with big feet to boot.

Though the two parents would seem to inhabit two different worlds, Hilliard observes, “we're both looking at two people who were highly guarded about their own physical and personal mythology.”

Perhaps because of this guardedness, both Hilliard and Sohier present photographs that are highly composed (and both parents played an important role in conceiving and orchestrating the shots). Nevertheless, the photos don’t feel staged, revealing something of the character of the subject and even, at times, the photographer.

In one photo entitled “Bubble,” Hilliard’s father reclines in a bathtub. Though the photo is composed with all the grandeur of the 1793 Jacques-Louis David painting “The Death of Marat,” what we see in Hilliard’s father is simple weariness, vulnerability and perhaps a certain amount of defiance. The shot was taken in a rehabilitation hospital where Hilliard’s father stayed after heart troubles.

In “Mum in her bathtub, Washington, D.C.,” Sohier also shows her mother in a seafoam green tub, covered in bubble bath foam. Sohier includes herself in the frame, seen in a mirror that repeats again and again like a funhouse attraction.

“That was a re-creation of what I used to do when I was a kid,” says Sohier. “I used to come and sit on the fuzzy blue toilet seat and watch her take a bath in the evening and she would pull this face cloth up over her breasts for modesty… She seemed regal to me in taking this bath.”

Clearly, this is a 1950s ideal of womanhood (though the shot was taken in 2002), underscored by the fact that Sohier’s mom wears perfectly applied lipstick and blush as she bathes. That, in short, touches on a key theme for Sohier, who has also made these photographs the subject of her book “Witness to Beauty.” Sohier’s mother held a certain idea of female identity which clashed with the ideas and ambitions of her daughter.

“The difficult years for me were when I was a teenager and I knew I wasn't measuring up to what she wanted from me and that she was worried about me, what would become of me as a woman,” says Sohier. “I wasn't dressing a certain way and acting a certain way. She wanted me to be OK. She wanted me to be successful. And you know it worried her.”

Hilliard photographed his father beginning in the 1990s straight up through 2017. His raison d'être was to present his blue-collar dad in the kind of august, sumptuous portraits reserved for royalty. (All of Hilliard’s photographs are diptychs or triptychs — a multipanel format he uses to guide the viewer’s eye.) Sohier’s aesthetic is different, at times recalling editorial fashion photography. We see mom taking baths and getting made up, but we understand that these rituals represent a certain mindset about life and femininity.

Also implicit in these photos is an acknowledgment of shifting dynamics and role reversals as, over time, the child becomes the parent and the parent becomes the child. Hilliard’s father, at the age of 87, now has advanced dementia and lives in a nursing home in Chelmsford. Sohier stopped photographing her mother when she reached 87, preferring to limit her photos to her mother’s prime years. Sohier’s mother is now 92 and lives with her boyfriend in Washington, D.C.

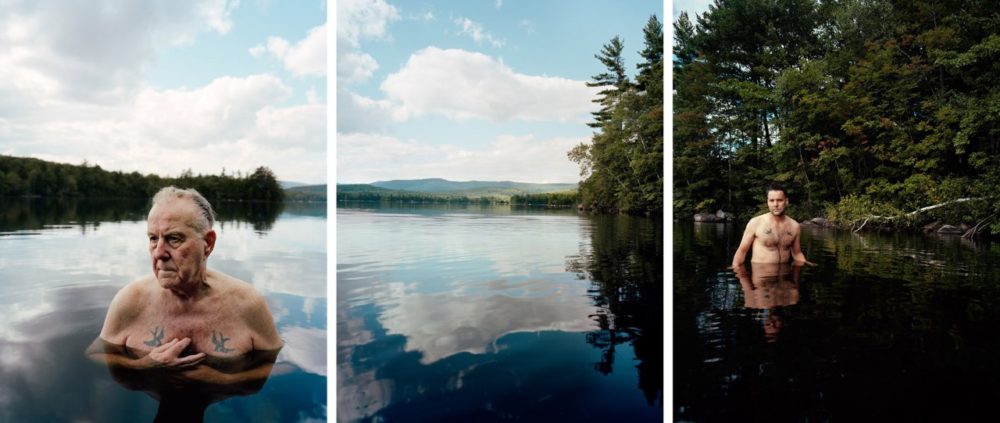

In one of Hilliard’s photographs, entitled “Rock Bottom,” father and son stand in a lake. On the left panel, Hilliard’s father stands chest-high in water, tattoos visible. Hilliard is pictured on the right panel, stomach-deep in water, with matching tattoos. In the middle of this scene is a void filled only by lake and clouds. For Hilliard, now in his 50s, the photo is representative of his own realizations about his father and aging.

“I am hardwired to become this man genetically,” he says. “This is what I'm going to be … But also, I'm not. I've worked hard to take the best of him but also push away what's not working. And so, I talk about this photograph in terms of determinism versus determination, the things that we can control and the things that are maybe predestined to be. And then there's that empty space in the middle… there's ultimately a division between us, but we're also connected.”

“Sohier/Hilliard: Our Parents, Ourselves” runs Sept. 7 through Jan. 5 at the Fitchburg Art Museum.