Advertisement

Fred Taylor, Who Spent His Life Supporting The Boston Jazz Scene, Dies At 90

The world of jazz has lost one of its greatest promoters.

Fred Taylor, who for six decades brought some of the biggest names in jazz and comedy to the Boston area, died Saturday at the age of 90.

Taylor was born in Boston on June 8, 1929, the son of Jewish parents who owned a mattress and upholstery business. The family moved to Newton when he was a young boy — and his love for jazz began when he heard Dizzy Gillespie’s 1944 hit “Salt Peanuts.”

After graduating from Boston University, Taylor worked as a mattress salesman for the family business in the 1950s. He played piano and dabbled as a drummer, but his real mission turned out to be music promotion.

Sue Auclair, a marketing professional who worked with Taylor for decades, said he would obsess over the most minute details. Here’s Auclair’s definition of a music promoter: "They rent the hall. They hire the the production team. They hire the band. They put the band up in the hotel. They pay for the advertising and the PR and all the marketing,” Auclair said. "They deal with all the backstage catering — and in Fred's case, he's famous for his backstage catering. Used to do it all himself. He'd be there with the coffeemakers and drive out to Costco and get big platters of food."

Taylor brought Boston a constellation of jazz giants — Sonny Rollins, Herbie Hancock, George Benson and Charles Mingus, to name a few — as well as mainstream megastars like Diana Ross, Bruce Springsteen and Bob Dylan.

One of the crowning moments in Taylor’s career came in 1981, when Miles Davis picked Boston as the place to launch his comeback after years away from the music business. Davis later said he wouldn’t have come to Boston for anybody but Taylor.

"We did eight shows there with Miles," recalls Auclair. "And it was sold out before we could even print the tickets.”

The eight-show run happened at a former disco called Kix, close to Kenmore Square, that Taylor transformed into a music venue.

The shows, Auclair said, were transcendent. "People were in tears. People were screaming, going crazy. And after each set of those eight shows, people wanted encores. And they all — I don't know how it happened — they just started chanting, 'We want Miles. We want Miles.' And he would come out, play an encore and they would keep screaming."

Advertisement

Taylor counted many music legends as his friends — one in particular, jazz icon Dave Brubeck. In a 2017 interview with WBUR, Taylor said their friendship began with a recording he made of one of Brubeck’s performances.

"At the end he says, 'I’d like to hear what you got,' " Taylor recalled in the interview. "So we jumped into my car. I drive to Newton — I’m still living with my folks — and I had a big hi-fi system, I plugged it in he says, 'Wow, that’s great!' "

The recording went on to become an early-era LP, which helped boost Brubeck's career and get him signed to Columbia Records.

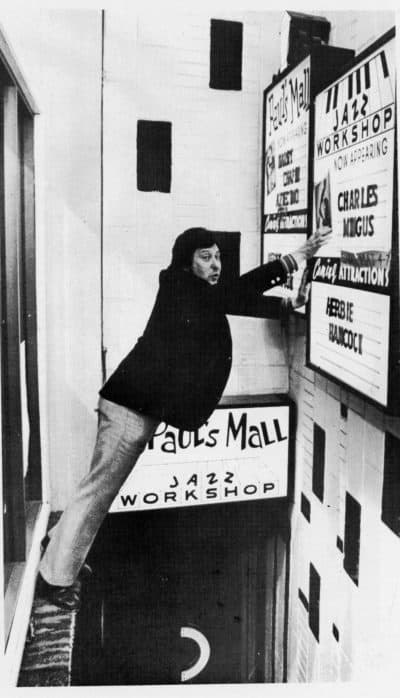

In 1965 and ‘66, Taylor and business partner Tony Mauriello (Taylor handled the talent, and he called Mauriello “Mr. Facts and Figures") bought two adjacent basement nightclubs near Copley Square — Paul’s Mall and the Jazz Workshop. They became the high notes of Boston’s jazz scene.

At Taylor’s 90th birthday party, Auclair recorded an interview with Sherry Smith, who started working at Taylor's clubs as soon as she could, on her 21st birthday.

"I absolutely fell in love with the environment, the music, the lighting, the photographs, the people, the smoke, the drug addicts, pimps, the hookers,” Smith said. "I just couldn’t believe that there was a world out there like that.”

Taylor also branched out to the comedy business, bringing in comics like George Carlin, Lily Tomlin and Richard Pryor.

By many accounts, Taylor was beloved among jazz royalty — not only because he could get you a gig, but also because of the kind of person he was.

“There are a few kind of characters in our community over the last probably a hundred years or so who aren't musicians,” said guitarist Pat Metheny, who Taylor hired to play the Jazz Workshop when he started teaching at Berklee.

But “whenever he's had something to say about the music, it's always been fascinating for me how he's connecting that to all of the opportunities he's had to be around the best musicians on the planet.”

Paul’s Mall and the Jazz Workshop were admired far and wide, but they didn’t have the capacity to bring in enough revenue to pay the big acts. The clubs closed in 1978 — after Taylor and Mauriello were unable to find an appropriate space to move the clubs — with B.B. King and Milt Jackson taking the final bows.

After that, Taylor and his partner bought the Harvard Square Theater. According to Taylor’s account the movie theater was a lucrative business, and they sold it to a national chain in 1986.

His next big undertaking was Scullers Jazz Club, where he became entertainment director in 1990.

"It was basically just a hotel lounge when he got there that sometimes had music," said local jazz historian Dick Vacca. Vacca helped write Taylor’s autobiography, set to be released next spring.

"He made the business," Vacca said. "He did a lot of work and he innovated and he brought a lot of people into town. He was heartbroken when they told him that they were done.”

Despite his ability to bring in the biggest stars, Taylor was always welcoming new talent into the jazz scene. Berklee professor and jazz trumpeter Jason Palmer says Taylor took him under his wing after he graduated from New England Conservatory, hiring him to headline at Scullers Jazz Club.

"He really took an interest,” Palmer said. “That was one of his hallmarks, finding young talent and then just giving them a platform to perform and giving them a chance to build an audience.”

"Fred’s a gem,” Palmer added. “He’s a national treasure. An international treasure."

In 2016, when Taylor was 88, Scullers let him go after a 26-year run. Some musicians talked about boycotting the club, but Taylor insisted against it. That’s because, for him, it was always about the music.

“You gotta keep that forward momentum. I mean memories are good, but don’t get caught up and stay there."

Fred Taylor

"He does it for all of the most pure, beautiful reasons," said saxophonist Grace Kelly. "He will be the first person to see a show and call someone up and be like, 'Oh my God, this talent!' "

Taylor discovered Kelly when she was just 13. She’s since gone on to become one of the biggest up-and-coming names in jazz.

"It's not all about numbers [for Taylor],” Kelly said. "It's not about, 'Oh, we didn't sell this amount of tickets.' The first thing is: 'What was the music like? What was the artist like?' "

On Taylor’s 90th birthday this past spring, Kelly’s parents hosted a celebration at their home in Brookline. Taylor did what he called a "sit-down" comedy routine and impersonated some of his favorite comics. Then he recalled advice once given by Duke Ellington: to stay focused on current projects rather than the past.

“You gotta keep that forward momentum," said Taylor. "I mean memories are good, but don’t get caught up and stay there."