Advertisement

Review

The Latest BSO Commissions Are Beautiful But Fail To Distinguish Themselves

During the five years Andris Nelsons has been music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, he’s been especially praised for his performances and recordings of Shostakovich (winning a couple of Grammys) and for the number of new commissions. Commendable, but…

For me, the Shostakovich performances, though brilliantly played, have lacked character, and given the astoundingly high level of earlier BSO commissions (Stravinsky’s "Symphony of Psalms," Bartok’s "Concerto for Orchestra"), the recent commissions have seemed mostly minor.

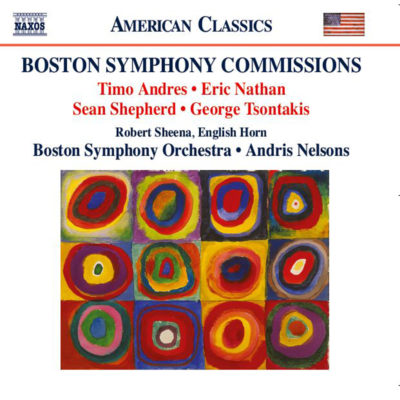

As it turns out, I’m not alone in my opinion. In a recent article in The New York Times, critic David Allen took on the state of the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Nelsons: “A Curious Timidity at the Boston Symphony” reads the headline in the hard copy of the paper. “If Mr. Nelsons has stalled in the old,” he writes, “he is also a less than thrilling spokesman for the new.” And Allen refers briefly to the new Naxos CD “Boston Symphony Commissions,” which includes four of the 17 world or American premieres Nelsons has conducted — music, Allen writes, “all of a more or less conventional kind.”

I have no serious disagreement.

Three of the four American composers on this new album — Eric Nathan, Timo Andres, Sean Shepherd — were born between 1979 and 1985 and were all Tanglewood Music Center composition fellows. The fourth composer, George Tsontakis, was born in Queens in 1951. All these commissions were composed in the last two or three years. All these composers have achieved distinction. Yet none of them seem to have as distinctive a voice as some earlier BSO commissionees, like Yehudi Wyner and Gunther Schuller, whose commissions were awarded Pulitzer Prizes, or such immediately identifiable composers as John Harbison, Augusta Read Thomas, Unsuk Chin (why isn’t there a woman composer on this album?), or Michael Gandolfi, let alone Stravinsky, Bartók, or Elliott Carter.

My problem with a lot of contemporary music is that the orchestration — intricate and surprising tone colors and instrumentation, complex and surprising rhythmic shifts — seems more important than a compelling through line, or truly heartfelt expression of complex feelings, or — God forbid — a memorable melody. What is offered as experiment seems already too familiar. Haven’t I heard music like this before, accompanying some movie? (Not that I have anything against a great film score.)

Advertisement

A good deal of the music on this album falls into this faceless quality. Still, this is a fairly attractive collection, not at all hard on the ear (although I periodically find my ear drifting off). In Andres’ “Everything Happens So Much” (the title, we’re told, comes from “a surreal Twitter account”), a single musical wave (sometimes in counterpoint with itself) winds or skips its way through a charming kaleidoscope of shifting tempos and piquant colors, with a hauntingly quiet ending. It takes only 11 minutes but seems maybe a couple of minutes too long.

The four movements of Shepherd’s “Express Abstractionism” convey his response to five different artists: Alexander Calder (turning slowly, more sinister than playful), Gerhard Richter (ominous and explosive, subtitled “The Rainbow Inside a Bolt of Lightning”), Wassily Kandinsky and Lee Krasner (an odd pairing of almost polar opposite expressionists — the chugging and swirling of this short movement seem plausible if not revelatory), and Piet Mondrian (ending the whole cycle with an unexpected slow movement titled, and complexly punctuated, "The Sun, or: The Moon, or: Mondrian"). Listening to this piece I might possibly have guessed Calder and Richter, but none of the other artists, and I’m afraid very little of it stayed with me after it was over.

Nathan’s “The Space of a Door” seems to have more literary content (the title comes from Samuel Beckett). The composer says that what inspired him was visiting the Providence Athenaeum for the first time. In the big loud C-major chord that triggers this piece, we are meant to hear the opening of a door. The liner note tells us that the composer was inspired by a similar chord in Bartók’s opera “Bluebeard’s Castle,” in which there are many doors. Nathan says that he was also thinking about his musical mentor, the much-admired American composer Steven Stucky, who recently died. Not every moment in this piece feels as fresh as the best moments, but I’m happy to come along for the ride. The various rooms these doors open to are interesting and sometimes scary places. A violin solo near the end is suddenly very moving. And a moment of genuine emotion is most welcome.

In some ways, the Tsontakis piece is the most compelling and seductive, maybe not surprising since he has enormous help from his soloist, the BSO’s soulful English horn virtuoso, Robert Sheena. The piece is called “Sonnets: Tone Poems for English Horn and Orchestra.” The four movements, ranging in length from just under four minutes to almost eight, are each based on a different Shakespeare sonnet (the BSO commissioned this for the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death).

The first movement is the famous Sonnet 30, “When to the Sessions of Sweet Silent Thought.” Tsontakis tells us that the “dear friend” about whom Shakespeare is thinking, reminds him of his teacher, composer Roger Sessions (sessions/Sessions!). Perhaps my favorite section of the whole album is Tsontakis’ second sonnet, set to Shakespeare’s Sonnet 12, “When I Do Count the Clock That Tells the Time,” a poem about the need for bravery in the face of inevitable death. Here Sheena conveys the lonely passing of the seasons. I’m not crazy about the cataclysm this builds to, but the quiet sections are truly beautiful and moving.

After the scherzo — a slightly overweight but fast-moving rondo inspired by Sonnet 60, “Like As the Waves Make to the Pebbled Shore” — the whole set ends with what Tsontakis says is the only sonnet in which the English horn “sings” every line of the poem. It’s Sonnet 75, “So You Are to My Thoughts As Food to Life." I try to follow along, and can’t seem to find in the prosody of the music a match for Shakespeare’s iambics. It’s a serious section, and the whole piece has great integrity. But for me it’s the second movement that really stands out.

But The New York Times' David Allen is right. There’s nothing very radical or challenging here. The playing is as always beautiful. But I can’t quite make out how big a part Nelsons himself plays in conveying the best moments, and since even the best moments, however attractive they may be, get a little lost in the relentless — and safe — stylistic similarity, how big a part he plays in allowing all these pieces to sound so much alike.