Advertisement

Old Growth, New Problems: The Battle Over Tree-Cutting In Cambridge

Resume

Lifelong Cambridge resident Peter Cohen loves trees. He grew up climbing and admiring them, and as an adult and homeowner, he puts a lot of thought and care into the ones in his yard. And Cohen has a big yard by Cambridge standards.

Walking around his property near Porter Square, Cohen describes how things have changed in the 25 years since he moved here with his wife and kids.

There’s the once-small elm tree in his front yard that has grown so big, the fence between it and the street now bows out. There’s a stand of small pine trees that he planted after his hemlocks were killed by invasive beetles. And there’s the million-dollar condos a developer built next door.

“This thing next to us is very big, it’s very close to our property line and it casts big shadows where we used to have a lot of light,” he says.

The condos also have windows that look straight into his backyard. There’s a Norway maple tree between the two buildings, but because it’s so tall, the trunk is the only thing blocking the view. Cohen says he’d like to cut down this tree down and plant a row of shorter evergreen trees to get some privacy.

“The alternative is to basically put an 8-foot fence, which wouldn’t be very nice for them to look at, and wouldn’t be very nice for us to look out,” he says. “But now I have a problem. There’s an ordinance that says I can’t take down the Norway maple.”

Welcome to Cambridge, where people can’t cut down “significant” trees — one that are at least 8 inches in diameter about 4-and-a-half feet off the ground — on their private property.

The City Council passed this tree cutting restriction -- what many residents call "the moratorium" — last year, after researchers found that 72% of all canopy loss in the city over the last decade occurred on private property. Violating the policy will result in thousands of dollars in fines, though it’d be hard to find an arborist willing to defy the rule in the first place.

There are exceptions for diseased, dead or dangerous trees, but to Cohen, even these are fraught. To show why, he points out two other Norway maples in his yard. From a distance, they look fine. But up close, one looks especially sickly — the bark is peeling away from the trunk and there’s a black patch of rot near the base.

“A number of tree people have looked at this and they said, ‘you know, that is dead, dead, dead,’ ” Cohen says. “They could easily fall on my house and damage it, they could fall on one of the cars in the driveway, on my neighbor’s driveway, so just public safety would militate in favor of removal.”

Under the amended ordinance, he can have these trees removed, but first he needs an arborist to certify that they’re dead.

“A certified arborist is supposed to come out and look at this obviously dead tree and say, ‘Oh yes, this is a dead tree.’ Then they take a form, fill it out and say 'I’m a certified arborist. This is a dead tree,' ” he says.

Getting that certification isn’t cheap. Most arborists charge between $250 and $300 per tree, according to the city’s Department of Public Works.

“That’s a lot of money. And if I spend it on the certification, that’s [money] I don’t have to either maintain other trees or plant new ones,” Cohen says.

Not everyone feels the moratorium is unreasonable. As climate change accelerates, environmentalists and urban planners across the country have become increasingly concerned with preserving tree canopy. And in Cambridge, where even an aggressive planting program wouldn’t be enough to reverse the canopy loss, many environmentalists are focused on preserving older, leafier trees.

“Trees are one set of stakeholders, and they need to be prioritized more than we have in the past,” says Cambridge resident and former Vice Mayor Jan Devereux, who voted in favor of the restrictions while she was still on the council.

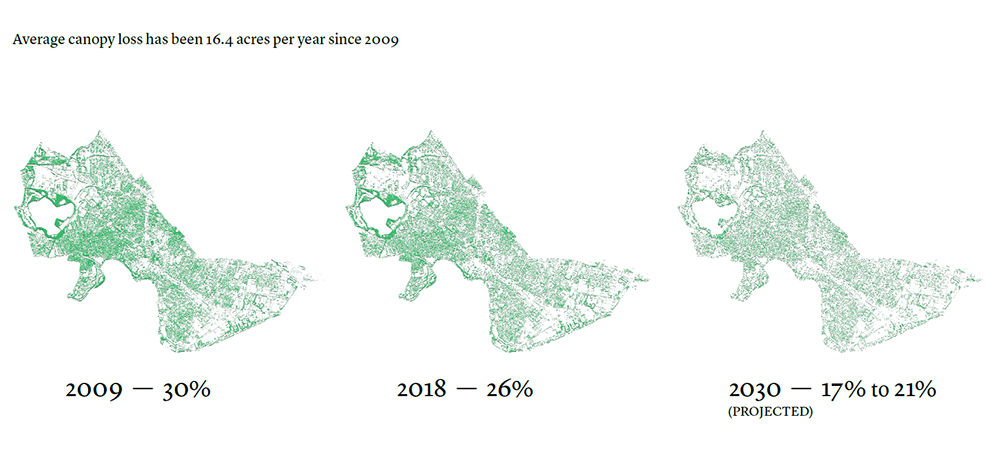

The city had been collecting data about canopy coverage for a few years, and “we noticed between 2009-2014, there was a pretty substantial loss,” Devereux says. In 2009, the city’s canopy coverage was 30%. In 2014, it was 26%. The city was losing about 16.4 acres of canopy annually, enough to cover 12 football fields.

Project that out, “and we could be down in the 17% range by 2030. It was a real wake-up call," Devereux says. "We knew that we needed to act [quickly] to get ahead of the problem.”

Before the ban went into effect, Devereux says the city had little control over trees on private property.

“And that’s sort of part and parcel of the notion of, ‘if I want to cut down a tree in my backyard, that’s none of your business.’ " she said. "Well, we started to think, ‘Hey you know, it may be part of our business.’ ”

Massachusetts towns like Lexington, Arlington and Concord have had rules about removing trees on private property for years, so Devereux says she and others on the council felt they were in good company. Plus, the timing felt right; Cambridge had just started the process of designing a master plan for its urban forest, so why not halt all tree cutting until the plan was finished?

(Contractors hired by the city submitted a 264-page technical report in November, but it’s unclear when the final plan will be published.)

When the idea for the moratorium came before the council last year, not every member was thrilled with the prospect, but it passed 7-2 and went into effect in March 2019. A year later, with the moratorium set to expire on Feb. 25, the issue is once again before the city council.

At a public meeting Wednesday, residents debated whether they should scrap the ban, or renew it and give the Department of Public Works and City Council an opportunity to work out a more nuanced and comprehensive set of tree rules.

Some of the ideas for this new ordinance include whether there should be different standards for invasive species, and whether there’s a way to reduce the cost of a tree assessment for homeowners — perhaps the city can use its arborist or offer a rebate, one resident suggested. Another option people discussed was creating a tree replacement system so that if someone wants to cut down a tree, they can either pay a fee or plant a new one.

A lot of the suggestions seem reasonable and straightforward -- until you start talking about details. Then, even something like calculating the fee someone would pay into the tree fund gets complicated.

There are a lot of ways to calculate a tree’s worth, says Maggie Booz, co-chair of the public planting committee in Cambridge. Should you factor in any of the tree’s ecosystem benefits — cleaning the air, providing shade or sequestering carbon — or just come up with a price based on the size of the tree? And if it’s the latter, do you do it based on the trunk diameter or area?

“We really want to deter people from cutting down trees. We don't just want them to pay some dollars per caliper inch,” Booz says. “But, I mean, no one can afford $70,000 to cut down one tree. And that’s the kind of calculations you’re talking about when you calculate for area.”

According to Deanna Moran of the Conservation Law Foundation, Cambridge isn’t the only municipality grappling with these decisions. Designing a comprehensive and fair tree ordinance is always hard and almost always full of trade-offs.

"There are no off-the-shelf solutions,” she says.

In a densely populated place like Cambridge, trees also compete for space with a lot of other things — new housing, sidewalks, parking spots, power lines, vegetable gardens and even sunlight for solar panels.

“We deal with these issues at much greater level than some of our peer cities in other parts of the country do,” Moran says. There’s little to no research about what policies work, which doesn’t help make things any easier for city leaders.

Whether Cambridge extends the tree cutting moratorium before it expires next month remains to be seen. But two things are clear: canopy loss on private land is a problem, and no one is totally sure how to fix it.

This segment aired on January 24, 2020.